Encyclopedia Dubuque

"Encyclopedia Dubuque is the online authority for all things Dubuque, written by the people who know the city best.”

Marshall Cohen—researcher and producer, CNN

Affiliated with the Local History Network of the State Historical Society of Iowa, and the Iowa Museum Association.

AFRICAN AMERICANS

AFRICAN AMERICANS. In a study of Iowa's history prior to the CIVIL WAR, Dubuque was the only place in the state that had a sizable black community. In 1840 seventy-two African Americans lived in Dubuque giving the city Iowa's largest black population. (1) By 1850, however, while Dubuque white population had increased ten-times, the population of blacks had fallen to 29. This decline can be attributed to two factors: 1) a general decline in LEAD MINING and related activities needing manual and day laborers and 2) a lynching in 1840. (2)

The socioeconomic-occupational status of blacks from 1850-1920 remained relatively unchanged as day laborers and house servants (3) In 1850 only two of the 29 blacks in the city were identified as self-employed--barbers. In the late 1850s one, Agnes Arthur, was listed as operating a boarding house. (4) In 1870 there were only three self-employed blacks--two barbers and a blacksmith. The 1900 census found only black engineer who worked aboard a boat in the ICE HARBOR. There were also two painters and one bricklayer. By 1910, semi-skilled black workers disappeared and in 1920 the only "prominent" black resident was a minister. The black population from 1870 to 1920 fell to 76--(equal to one-tenth of one percent). (5)

The lynching in 1840, an isolated incident of violence in city's early history, was that of Nathaniel Morgan, a young free black who worked as a cook and waiter at a local hotel. Morgan was accused of stealing a truck of clothes. He was whipped and beaten by a mob which eventually hanged him when the trunk could not be found. The members of the mob were arrested and tried, but then acquitted on the grounds that their "intention to commit murder had not been proven." (6)

The case of RALPH in 1839 or the 1851 repeal of the 1839 territorial law banning interracial marriage did not suggest that Iowans viewed African Americans as political or economic equals. The Iowa Legislature passed what became known as BLACK CODE which slowed the movement of free blacks into the territory. In 1839 the first law prevented "blacks and mulattoes" from settling in Iowa if they did not possess "a certificate of freedom and the ability to post a bond of $500" showing that they "would not become a public charge." (7) The second law passed in 1840 prohibited interracial marriages. (8) In 1844 Edward LANGWORTHY, at the state constitutional convention, asked the other delegates to pass his proposal that the legislature prevent black and mulatto settlement in the state. The measure was adopted, but removed at a later meeting. The convention, however, did exclude free black males from voting and serving in the state legislature and militia. (9)

The PANIC OF 1857 was a nationwide calamity that did not spare Dubuque. Between 1840 and 1860 the white population increased sixteen-fold while the black population fell from 8.6 percent to .5 percent. This was at a time when Iowa's black population (between 1850 and 1860) tripled in the state. (10)

Dubuque's economy in 1860 was dominated by MINING and commercial capitalism; in the absence of industries most of the working class population was involved in manual labor. (11) Most German workers were skilled artisans. The Irish were generally unskilled workers. In Europe, the British ruled the Irish under codes known as "Penal Laws" that resulted in oppression and exclusion. When they arrived in America, the Irish were thrown together with blacks in low income jobs by society on the east coast. The resulting socialization led to mulattoes either referred to as "(word omitted) turned inside out" or "smoked Irish." (12) Carrying these bitter memories westward, Irish saw blacks as competitors for jobs.

Contributing to division among races were the writings of Dennis MAHONY, editor of the Dubuque Herald and a strong southern advocate. The Dubuque Herald on April 23, 1861 carried the following editorial:

Free Blacks Coming North. The boats from St. Louis last Saturday

had several hundred free Negroes aboard, seeking homes in the

"Land of the Free." A public notice was given last week that all

free blacks must leave that city and State in five days. This

caused a very dark colored stampede. We are glad that only a very

few stopped at Dubuque. (13)

The following editorial appeared first in the LaCrosse Democrat but was reprinted in the Dubuque Herald Mar. 16, 1862. [Note: An inflammatory word has been removed so that the editorial can appear here].

All for the (word removed)- We have figured out the

cost of the present war in cash to date, and find that

the Government has already expended enough money to

purchase every (word removed) in the United States

and to furnish each one with a flannel shirt, a copy

of the New York Tribune, and a quill tooth pick.

Nothing like meddling with that which is none of our

business. (14)

On November 14, 1862 the Dubuque Daily Herald became the Dubuque Democratic Herald further signifying its political stance. (15)

The Herald's anti-black position intensified in 1863 when Stilson Hutchins became the acting editor in Mahony's absence. (16) In an editorial on April 5, 1863 he wrote:

Who wants to vote the (word omitted)-emancipation ticket? Who

wants Iowa covered with indolent blacks? Answer at the polls. (17)

The following article appeared in the Dubuque Democratic Herald on September 10, 1864. (18)

Happy Are We, Darkies. So Gay--Yesterday morning a dark cloud

was discovered coming up Main Street which took the citizens

by surprise...The cloud was ten colored recruits...They slept

in the room in the St. Cloud block and are an orderly,

respectible (sic) looking set of men, and don't smell very

bad although yesterday was rather warm. If they every get out

of the army their troubles will then just commence.

The racism in some cases can only be seen today when the meaning of words today is understood. The following editorial appeared in December 1864. The definition of "contrabands" appears in parentheses: (19)

Street Lamps Opaque-The street lamps were not in a state of

illumination last evening, and the moon was in company with

them. It was almost as dark as a regiment of "contrabands"

(African Americans). Where was the lamp lighter?

On October 15, 1864 the following news article appeared in the Dubuque Democratic Herald showing a grudging admiration for a surprising subject: (20)

A Black Broker--Our citizens had a practical illustration

the other day of a darkey dealing in white men. A negro,

from some interior town, presented himself at the Provost

Marshal's Office as a volunteer to fill the quota of his

town, and was also authorized, and furnished with the

means, to buy enough men to fill the quota. The flourished

among the white brokers, and was a formidable rival,

bidding up in a spirited manner. He got one white man for

$700, and would pay that much for several more, but he

happened to open negotiations with a Copperhead who

gave him a blow over the peeper, and the darkey left for

home soon after with a black eye, and has not been seen

since. He is several degrees above those ranting, howling

abolitionists who blow war all the time, but never enlist

themselves. He is going to the front 'wid de white fokes.'

Encouraged to leave the South was not a promise of a better life.

The Charity of Color-A benevolent soldier man, whose name

we did not learn brought from the South a colored woman

some eight months ago. He had assisted her and fifty or

more other colored persons to leave the South and seek

their fortunes in the kindly North. He gave the women to

some family acquaintances or relatives here and she worked

for nothing just as well as the abolitionists accuse those

of her color doing in the South. All was well as long as

she did not cost anything. But hereby hangs a tale. She is

about to become a mother, so the mistress drove her away

and she was obligated to sleep in an outbuilding on Tuesday

night without fire. Yesterday the Overseer of the Poor was

endeavoring to find some place the poor creature could be

comfortable. Where is all the abolition philanthropy of

those who wanted these colored fellow citizens of African

descent to come North? They welcome them as long as they

can get their work for nothing, but young mulattoes are

decidedly at a discount. (21)

The issue of black voting came to Dubuque in 1865 when the lieutenant governor came to the city to speak. The Dubuque Herald referred to this official as the governor's "man Friday" with not so subtle racial implications and went on to state:

His "man Friday," obeys orders and will start the "billows"

(sic) tonight. Those wishing to witness the exhibition of

negro-equality logic will be present. (22)

The following day the Herald reported that a "baker's dozen of African admirers" attended the meeting. While no report was made of the speaker's arguments, the article mentioned that Delos E. LYON was pinching his leg to stay awake and that by the end of the speech the empty seats in the audience "demonstrated the moving power of the lieutenant governor's logic." (23)

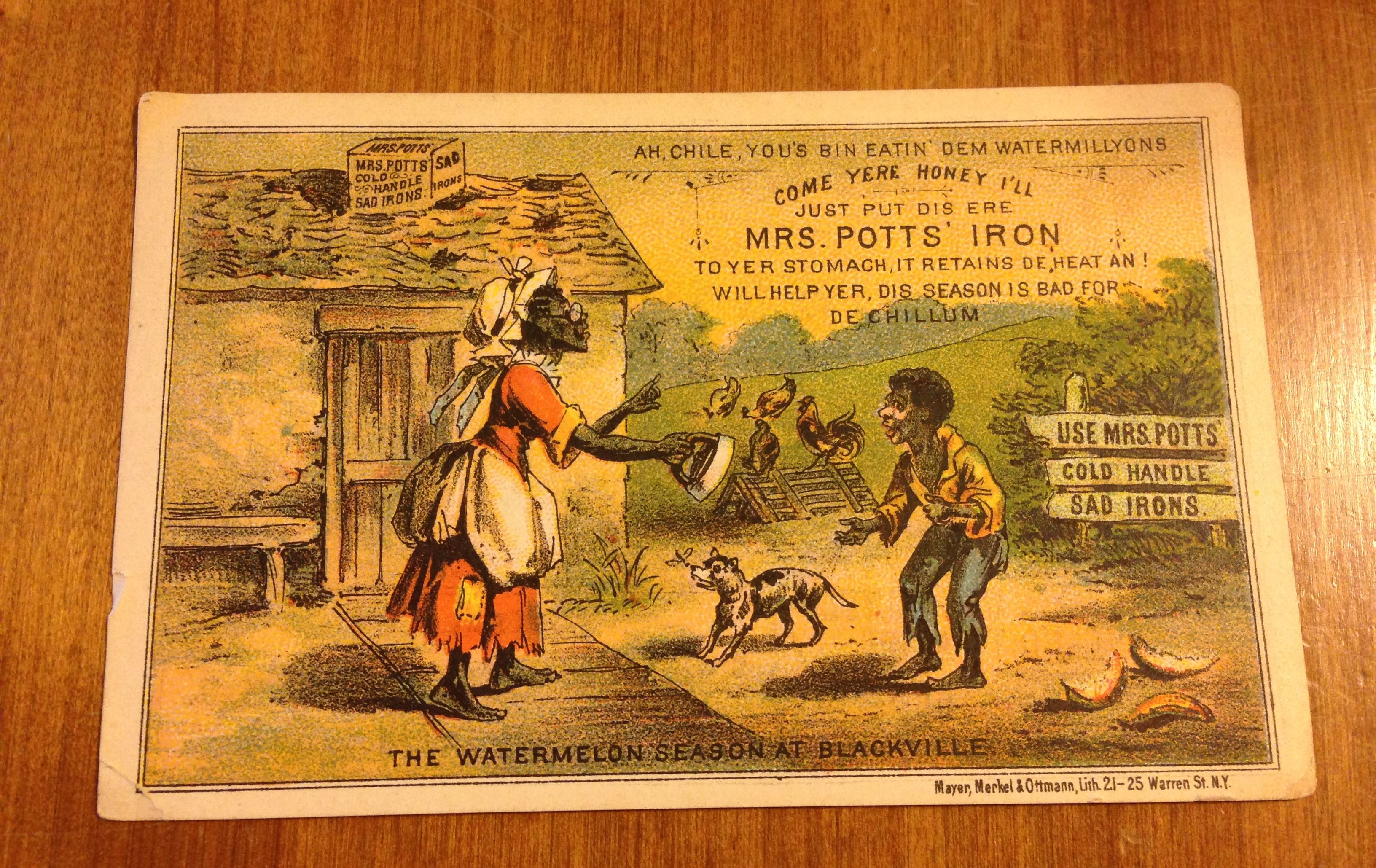

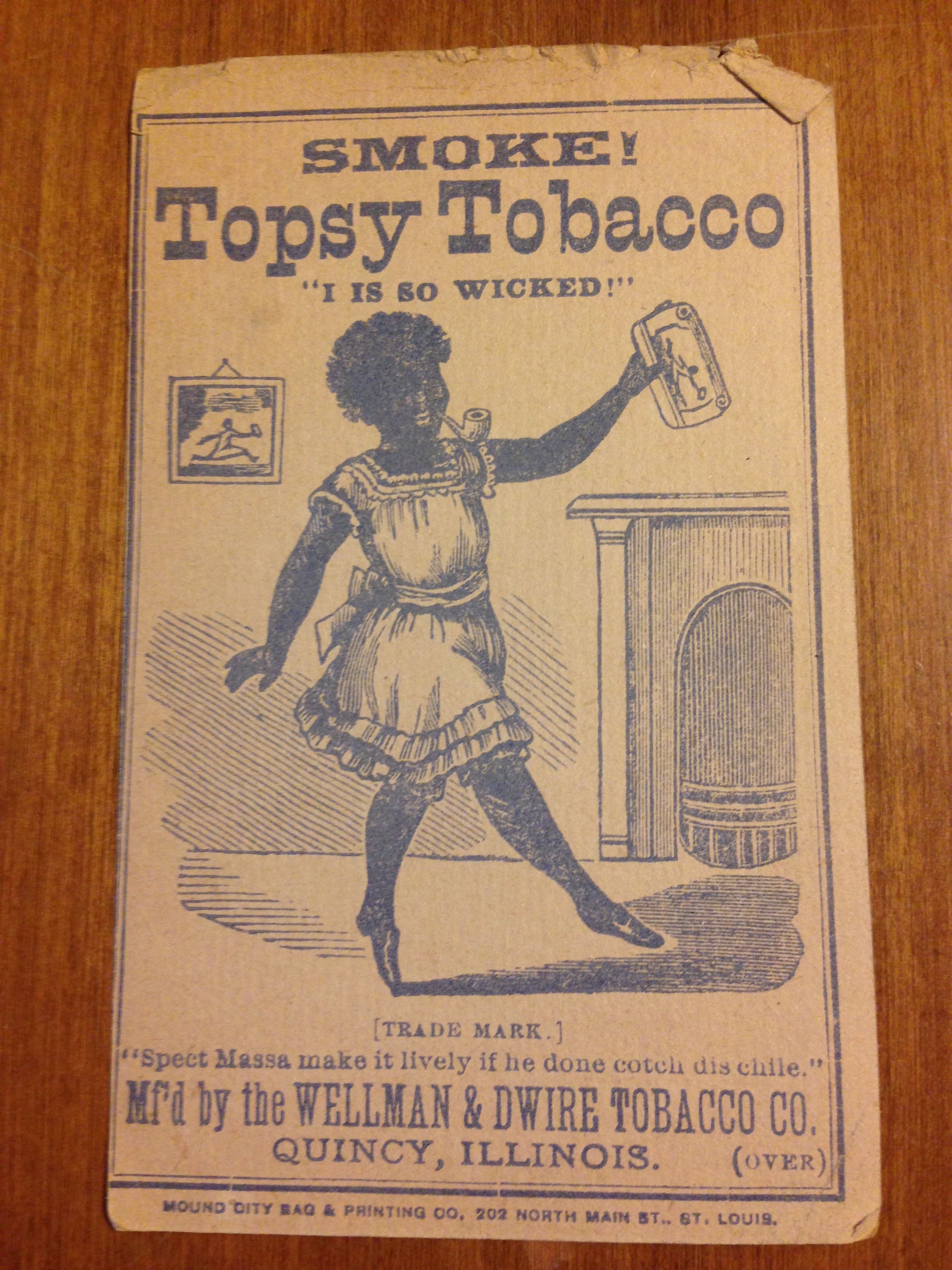

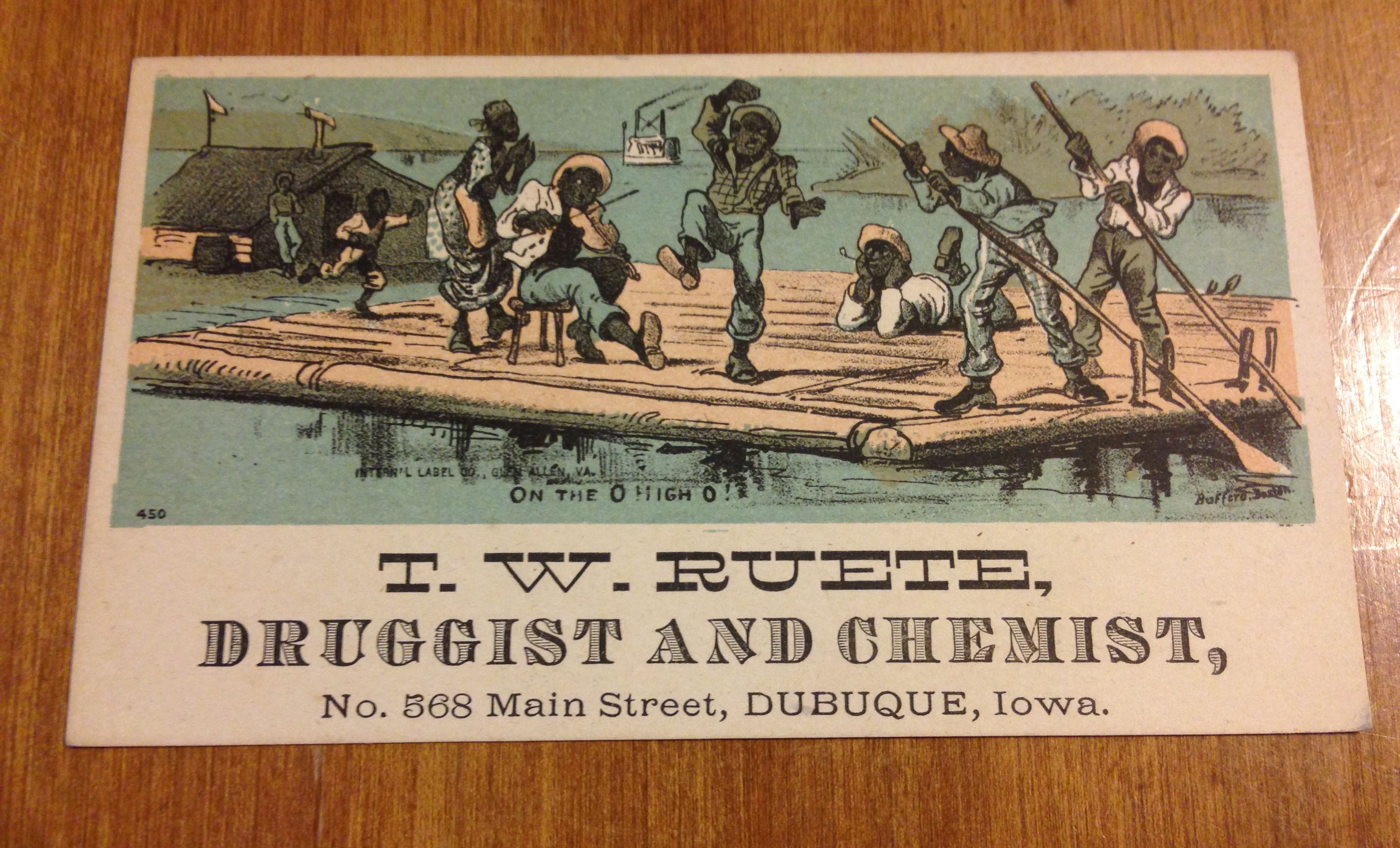

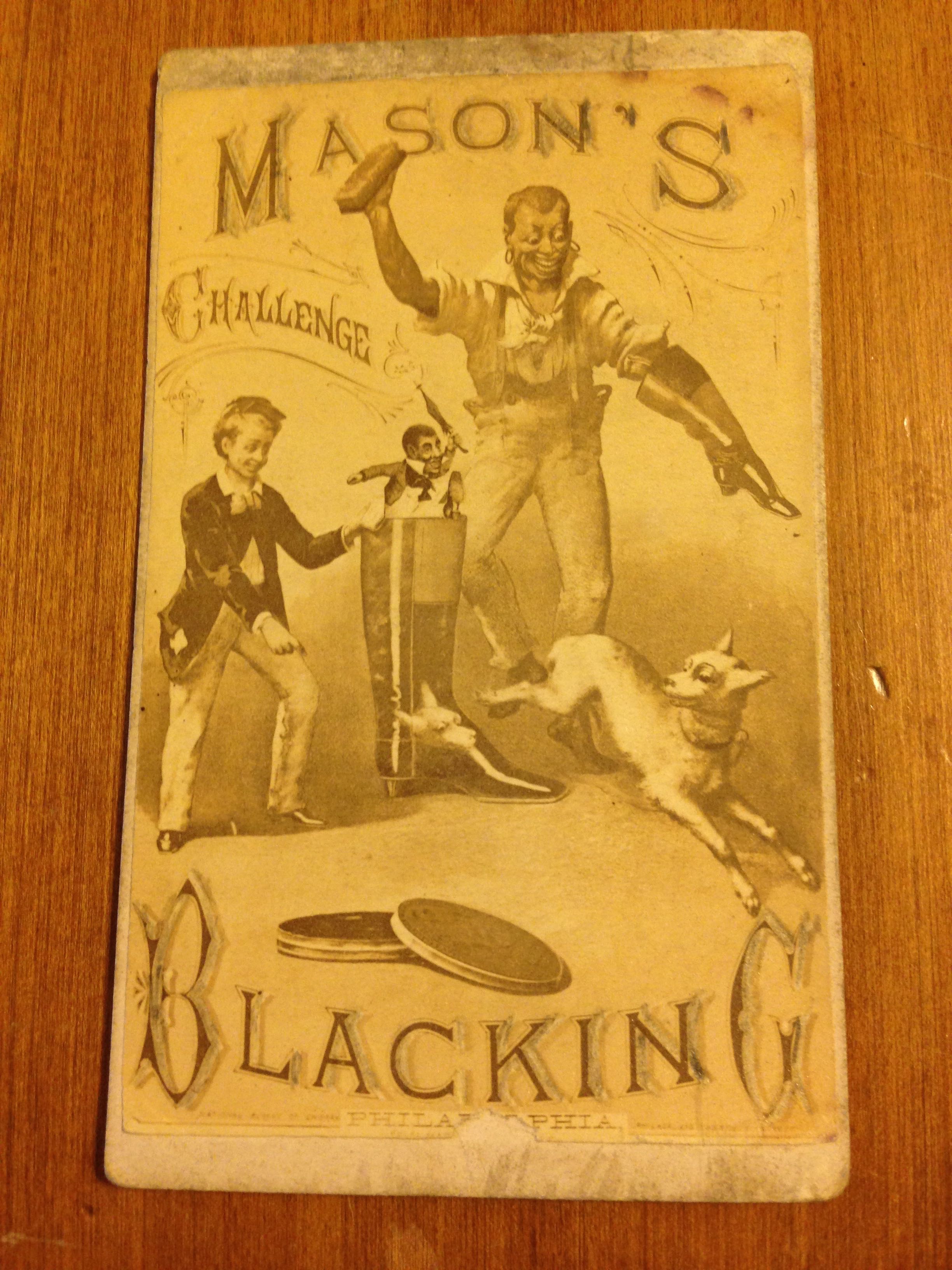

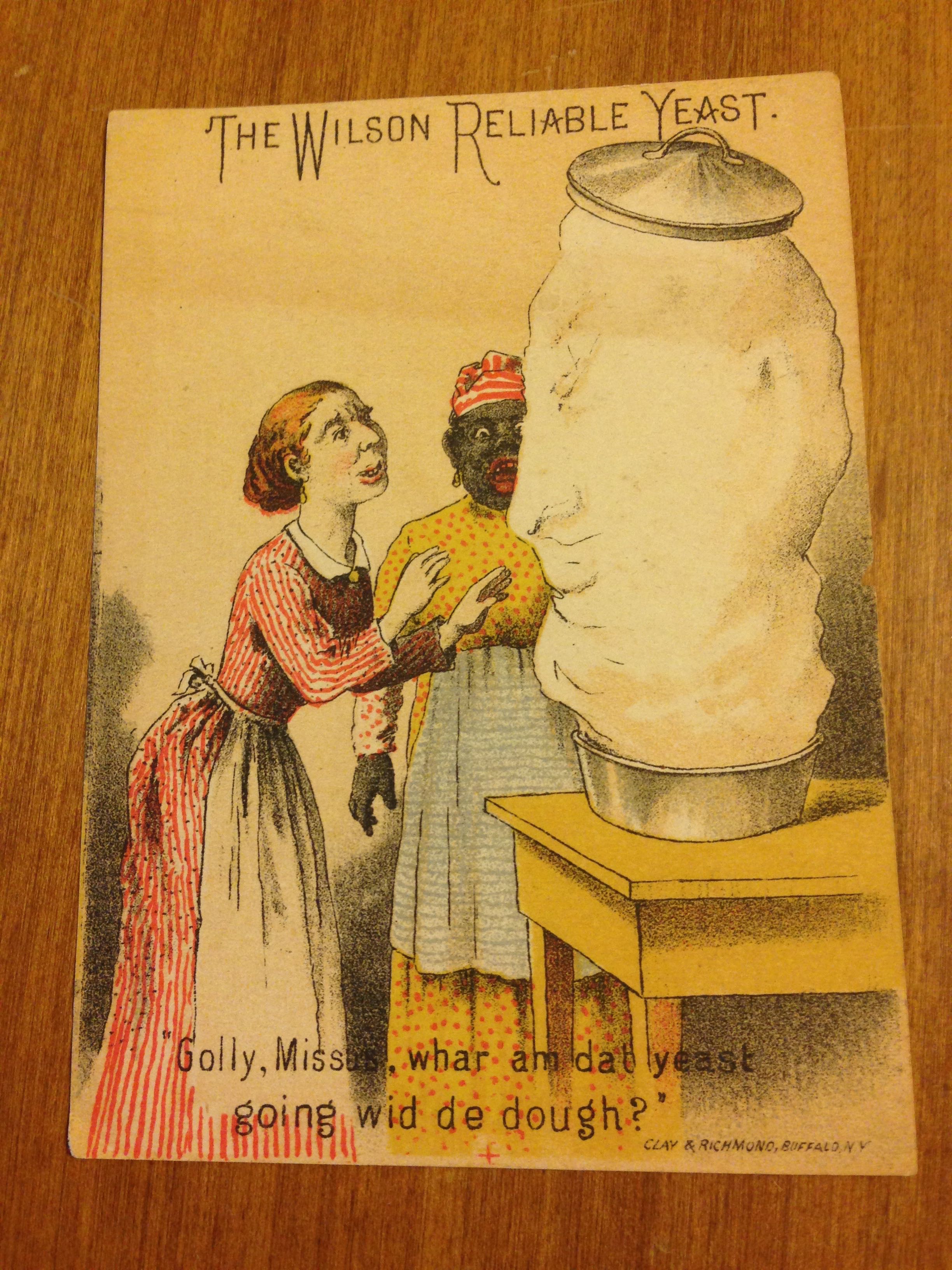

Trade cards were the means of advertising a business. In the 1800s stereotypes on these cards of African Americans ridiculed their intelligence, speech, morality, industriousness and foods.

After the Civil War, some blacks found work on the riverboats where they found support among their fellow workers. In 1866 the white members of a crew on a packet boat went on strike for better pay. While many of the white crew members had some money for food, the thirty blacks had nothing leading to the following story in the Dubuque Daily Herald: (24)

Commendable Sympathy--We are informed that the whole crews

that lately left the service of the Packet company were

soliciting subscriptions yesterday, to aid the black crews

who are without money consequent upon their refusal to

work as per contract. The company owes each man $37.80,

not one cent of which will be paid unless they resume work

and continue until the season of navigation closes. In

passing a crowd of the black crews yesterday, one of them

was humming in melancholy tone the popular refrain:

All the work is dark and dreary

Everywhere I roam,

On darkies how my heart grows weary

Far from the old folks at home.

The efforts of the white boatman among the people of Dubuque had success: (25)

Helping the Blacks--The negro roustabouts of the Key City (ship)

who left the boat for an increase in wages are hanging around

the levee without a morsel to eat or a cent in their pockets

and would starve to death for all the notice the abolitionists

take of them. The copperheads are their real friends in their

hour of need. They have furnished them with victuals and

besides the $25 previously, collected $15 last Friday to

relieve their wants. Many a needy boatman has given liberally

to keep the poor blacks from starving, and they are beginning

to find out who are their true friends. The river men, that is

the white roustabouts and deck hands, take a lively interest

in their welfare, and will see to it that the poor negro is

supplied with food and clothing if nothing more. The boarding

houses, groceries, and bakeries downtown contributed a certain

amount daily to keep the thirty blacks from suffering.

Strikes spread to other boats in the late summer of 1866. The Dubuque Herald expected that the company would have no trouble finding plenty of men working along the river to be substitutes. (26) Instead, the company returned to Cincinnati, Ohio where 206 blacks were hired as strikebreakers to replace striking blacks and whites. (27) In August, the body of an African American, a "floater," was found in the Mississippi River. The Dubuque Herald commented, "We should not be surprised to learn of the recent importation all floating past here before a year expires. (28) When a "colored crew" left the city for their home in Cincinnati, the article went on to state "cologne must come down (in price) now...there is no use for it until next season." (29)

In September the new black crew members decided to strike. As reported in the Dubuque Herald: (30)

a sassafras colored (word removed), in town went down to the levee and

whispered something in their ears when they all left the boat in a body,

without any notice at all after she had been loaded in Dunleith and was

ready to start for this side of the river.

In response, the company sent an agent to Cincinnati to hire 300 whites to work as crew members. The newspaper commented that these strikes were not unexpected as "a (word removed) is no better than white man; they all want 'more." (31)

Businesses that did not discriminate had public opinion with which to be concerned.

To the Editor of the Dubuque Herald--Having recently been a resident of

the city, I would like to inquire whether it is customary for the land-

lords in first-class hotels to seat the colored with the white folks at

the table. Having been an eyewitness to the proceeding, we, for one,

protest against the custom of "mixing boarders" in this promiscuous

manner. We respect a negro in his place, and cannot but believe that

such a course will be injurious to the reputation of the House and

offensive to the traveling public. (32)

Although the legal standing of blacks changed, racism remained open in Dubuque. In 1866 the following editorial appeared in the Dubuque Herald:

A Colored Petition-A petition is being circulated through

town asking the Board of Education to provide schools for

the education of colored children. A Copperhead says that

if such schools are established "(word omitted) will

flock here in swarms to get 'larnin' and that the gas will

have to be left on all day to find the way through town."

A Democrat is asked if he would not rather have them by

themselves than mixed with the whites, and on this appeal

several have signed the petition. On the other hand, it is

argued that there is no employment here for any more darkies,

and no danger of them coming. (33)

Sometimes it seemed the writer was not aware of his/her racism. In a report on the newly opened school for blacks, an editorial in the Dubuque Herald remarked that the seventeen scholars came in "all sizes, ages, and shades of complexion, straight hair, curly hair and wool. They are quiet and orderly with a determination to learn something if they only get a chance." (34)

On September 12, 1867, 12-year-old Susan Clark was denied admission to Muscatine's Second Ward Common School Number 2 because she was black. Her father, Alexander Clark, filed a lawsuit to allow admission of his daughter to the public schools. In 1868, the Iowa Supreme Court held that "separate" was not "equal" and ordered Susan Clark, an African-American, admitted to the public schools. This effectively integrated Iowa's schools ninety-six years before the federal court decision, Brown v. the Board of Education in Topeka, did the same thing on a national scale. (35)

Legislative support passed for racial equality and blacks' civil rights. In 1868 Iowa residents supported a referendum allowing blacks to vote. In 1880 the word "white" was removed for qualification to serve as a state legislator. The passage of the Civil Rights acts in 1884 entitled African Americans

to the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations,

advantages, facilities and privileges of inns, public

conveyances, barber shops, theatres and other places of

amusement.

Passage of laws, however, did not ensure that racial prejudice did not occur. In Setember 1872, according to the Dubuque Herald, "a darkey, colored citizen, or (word removed) the reader may choose out either appelation (sic) he pleases, in obedience to the civil rights act was installed at one of the tables for breakfast." When she refused to serve the person, she was walked out taking most of the staff with her. The paper concluded the article with "This enforcement of the civil rights bill attests the truth of the old adage you can bring a horse to water but you can't make him drink." (36)

All was not work for African Americans living in Dubuque in the 1870s. On January 27, 1873 African Americans held a "black ball" in the DUBUQUE CITY HALL. In an example of reverse discrimination, a white woman who tried to enter the premises was escorted out by the marshal. The Dubuque Herald stated that the ten couples present "hoed it down until daylight." (37) Another dance was held for African Americans at the Dunleith market house in February 1873. The same white woman retaliated by not allowing her husband to perform with his band which played at the event. (38)

The black crew members of the "Belle of LaCrosse" walked off the boat in May over pay that had fallen from $45.00 to $35.00. Without food or lodging, they were allowed to stay city court room from Saturday until Monday. The wage issue was settled, and they rejoined the boat. (39)

Residents of Dubuque found in 1873 that the first black had been seated as a juror on the United States District Court of Iowa. The Dubuque Herald reported that Joel J. Epps, of Fayette County, "owner of one of the finest farms in the county and rated a clear-headed man" held the honor. (40) An article, however, without some kind of negative remark was rare. An article under the title "A Colored Knot," reporting the instance of a black man forgetting to get a marriage license included the derogatory comment, "Robert Glove and Hattie Delano, two of the colored aristocracy of the city..." (41) On August 24, 1873, the editors of the Dubuque Herald felt it worth the space to include the following as "news:" (42)

A gentleman color entered a bookstore yesterday and inquired,

"Mister, got any dem ar'tings you put letter in--I forgits if

dey are inwhelupments or overalls--jist give me ten cents wuf."

African Americans in 1873 met in the market hall on the evening of July 8, 1873. Those in attendance supported a proposal to celebrate the emancipation of slaves in the British West Indies in 1834 and the emancipation proclamation of Abraham Lincoln and passage of the 13th amendment to the United States Constitution. The event was planned for August 1st and black residents of Wisconsin, Illinois and Iowa were invited. (43)

Racial slurs in 1875 alluded to some of the legal rights won by African Americans. The following story appeared in the June 13, 1875, issue of the Dubuque Herald:

A good "yoke" is told on our friend Stammeyer of how he

was fleeced by a "fifteenth amendment" more recently

known as a "civil rights" member of the community. The

darkey was hired in advance clean a vault in the rear of

Mr. Stammeyer's property...The darkey worked a couple of

hours, made a hole in the ground, and bustled around as

though big things were to follow his efforts...Mr.

Stammeyer walked out the following morning to see a good

job done and lo and behold, his eyes and nose were

astonished. Sambo had departed leaving his job half done...

Mr. Stammeyer will not be confiding in the colored race.

They are no surer now than they were before the civil

rights bill was passed, and act like some of the "white

trash." (44)

In 1875 Dubuque's African American population let it be known that they wanted to join in the celebration of the 100th birthday of Irish patriot Daniel O'Connell. (45) The invitation was accepted by the O'Connell centennial committee and a meeting of African Americans was called. Mr. E. Blackstone stated the reasons why the invitation should be accepted as it was the first time African Americans living in Dubuque had ever been solicited to join any procession that would put them on anything like an equal footing. It was moved and seconded to wear the O'Connell badge and carry the American flag. It was then moved and seconded that all who would join in the parade should stand. The entire house was on its feet. (46)

While successes were achieved, there were instances of prior freedoms being lost. In 1875, the American senior body of the INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATION OF GOOD TEMPLARS voted to allow separate lodges and Grand Lodges for white and black members, to accommodate the practice of segregation in southern states in the United States. In 1876, British members failed in achieving an amendment to stop this, and left to establish a separate international body. In 1887 this and the American body were reconciled into a single IOGT. (47)

Dubuque took awhile before paying attention to the 1868 Iowa Supreme Court decision involving separate but equal education. The Board of Education in Dubuque disbanded the "colored" school in 1870 and admitted blacks to ward schools. Faced with great opposition from white residents, however, the decision was then repealed. The board president cited "mingling of the races" causing "discord in the school, and a virtual exclusion of the colored children. (48) In 1877 a group of black parents petitioned the Board of Education in Dubuque to send their children to public schools. The board voted against the parents, but the district court overturned the ruling. The all-black school was closed, and local schools became integrated.

Legislation passed in Iowa in 1892 desegregated public restaurants and bath houses. (49)

In November 1893, an all-black play, "Among the Breakers," was performed by members of the African American community in Dubuque. A drama critic of the Dubuque Herald commented that the play moved along smoothly and that Joe Norris, as a light housekeeper, did very well. The critic went on to say, however, that he would have "preferred to see Norris in swallow tail coat and white tie receiving visitors in one of Dubuque's finest homes."

Race relations remained strained as the twentieth century began. In 1906 a football team from Savannah, Georgia consisting of fifteen and one black player visited Dubuque. Staying in a local hotel, the manager refused to seat the black in the main dining hall. He was able, according to the management, to order off the menu and be served upstairs in his room. While the players accepted the idea, the teachers refused and left with the players to find another restaurant. (50)

In 1907 the all-black seven member Dixie Jubilee Singers, were invited to perform at ST. JOSEPH COLLEGE. College organizers tried to make housing arrangements in advance, but all except two hotel managers refused to accept the singers as guests." The group was eventually fed and housed on the college campus. (51)

Athletic ability among African Americans in Dubuque was being recognized nationally as early in 1918. In an article mentioning outstanding African Americans in sports, Edward Solomon "Sol" BUTLER was expected to show great ability during his college career. (52)

Until WORLD WAR I, African Americans were hired in low-status and low-paying jobs across the United States and in Dubuque. (53) As seen in the examples listed previously, black workers were seen as potential unskilled cheap labors who could and were used by employers to keep wages in general low. As was shown previously, they were used as strikebreakers. (54)

Organized labor made its appearance in Iowa during the last decade of the 19th century. Until the 1930s, the Iowa State Federation of Labor, an affiliate of the American Federation of Labor, was the legal representative of organized labor in Iowa and Dubuque. A survey of the Federation's annual proceedings from 1895, when the first convention was held, until the end of WORLD WAR II shows no reference to black workers or their rights. (55) The only statement supporting "equity to all men regardless of class, race, creed or color" was made in 1930 in support of a white labor leader in California. (56)

The black population in Dubuque by 1920 had dropped to 75. The MINING and shipping industries may have played only a small part in the movement of blacks out of the area. The first cross-burnings of the KU KLUX KLAN began in 1923. A huge gathering of Klan members was held off Peru Road in 1925. In 1926 the Klan marched through Dubuque and held another huge Konklave, a mass meeting of their membership, off Peru Road.

Award-winning columnist Nicholas THIMMESCH recounted his days as a groundskeeper around 1940 at the Dubuque baseball field:

Vagrant blacks were advised to get out of town by sundown as

they were in many habitats around the farmland...Many Dubuque

eateries and saloons, especially the second-rate ones had signs

in the windows,"We Do Not Cater To Colored Trade. (57)

Anti-discrimination feelings were also expressed. Thimmesch remembered teams wanting information about where they could order take-out food. When asked, him would jump in the bus with them and visit the CONEY ISLAND LUNCH where Jim Kerrigan served them at the counter while "white jaws of customers dropped" as the players' food orders were taken and served. (58) In 1933 Theatrece Gibbs became, as far as research can prove, the first African American in the United States ever elected captain of his high school football team. His teammates from DUBUQUE SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL would walk out of any establishment that would not serve him.

Prior to World War II, African Americans in Dubuque were legally unprotected. Although there had been communication with the [[NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE (N.A.A.C.P.), the organization's nearest branch was in Waterloo. (59) Public accommodations remained a problem even for the nationally known Duke Ellington Band which was denied a place to stay in the 1930s. (60) For individual cases, a late-night call from the Police Department might be made to a black family asking if they would take in someone turned away from the hotels. (61)

World War II did not bring racial equality although there were improvements thanks to the efforts of Eleanor Roosevelt. The Double V logo was designed by Wilbert L. Holloway, a Pittsburgh Courier staff artist in 1942. The logo, playing upon the V for victory campaign during the war was aimed at promoting victory in the war ... and racial equality at home. African American newspapers across the United States quickly endorsed the campaign and it became a nationwide phenomenon. Lapel pins, stickers, songs and posters promoting the Double V became popular emblems of support. (62)

By the summer of 1942, more than 200,000 individuals paid a nickel each to join Double V clubs. The clubs held rallies and marches to promote the contributions of African Americans in military service and draw attention to discrimination. The Pittsburgh Courier management saw the paper's circulation soar from 200,000 weekly readers to over 2 million by the end of the war. (63)

Even as the movement gained public support, the federal government had a different reaction to the campaign's success. African American newspapers were banned from the libraries of the U. S. Military and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (F.B.I.) sought to charge American publishers for treason. (64)

The reaction of the federal government to American publishers mirrored their reaction to African American sailors who went on strike at Port Chicago in southern San Francisco Bay. African Americans who volunteered for the Navy were given jobs loading ammunition aboard ships without being trained in the loading equipment. Increasing the danger was the fact that two ships were docked side by side while sailors were forced to race to see which ship could be loaded quicker. On July 17, 1944, an explosion rocked San Francisco Bay after an accident occurred at the naval yard. The disaster killed 320 sailors and civilians. (65) One month later, fifty African American sailors on strike protesting the lack of any new safety procedures were found guilty of treason and sentenced to up to eighteen years in prison. News of the conviction and the government's campaign against the Double V program would have necessarily made its way to Dubuque through African American publications printed in the state.

The growth of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in Iowa and post-World War II political support of African Americans slowly forced the Iowa State Federation of Labor (ISFL) to change. In 1950 a resolution was adopted that considered "any group of individuals, or organizations, which creates, or fosters racial, religious, or class strike among our people to be un-American, a menace to our liberties, and destructive of our fundamental law." (66) The CIO brought to Dubuque the question of racial equality at work and the need to pass the Fair Employment Practices Law. The organization also strongly supported the Supreme Court's ruling in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 while condemning the slow pace of progress in human relations everywhere in Iowa. (67)

In 1956 the CIO and ISFL and merged with the American Federation of Labor. In their first decade of merger, the organization passed many resolutions dealing with human rights, racial discrimination, and immigrant laborers' legal rights. The organizations' actions on racial equality and protection of human rights lagged from 1968 to 1994 when issues of unemployment, plant closings, and low wages took more attention. (68)

Only a few black families lived in Dubuque during the 1940s and 1950s. Active recruitment of blacks by major industries in Dubuque did not occur until the mid-1970s. (69) Among major employers to move to Dubuque which had a major impact was the JOHN DEERE DUBUQUE WORKS which came to Dubuque in 1946. A cluster of small brick homes known as "John Deere houses" were constructed on the far west side of Dubuque in the HILLCREST HOUSING DEVELOPMENT, but these carried the not-unusual-for-their-time clause in the abstract that the premises would not be sold to blacks. Nonetheless, Deere and Company did attract black employment but until the 1980s black employees at the manufacturing plant never exceeded .25 percent of the workforce. (70) Local blacks recall how people of color were greeted by police at the train station in the 1950s, and told to get right back on. (71) In the 1960s only two blacks were attending WAHLERT HIGH SCHOOL.

Efforts at encouraging racial understanding and INTEGRATION did take place. In 1961 OPERATION FRIENDSHIP was started. In 1962 ten white students from the UNIVERSITY OF DUBUQUE exchanged places with ten black students Johnson C. Smith College in Charlotte, North Carolina for a week. The students from Dubuque declared,"We're not do-gooders. We're here to enjoy it." (72) They were accompanied by Dr. John Knox Coit of the University of Dubuque, a professor of philosophy, who would trade places with a professor of from the southern college. (73)

In March 1969, Black Student Union members charged LORAS COLLEGE with institutional racism. Among their demands were the removal of the basketball coach and the introduction of African American studies. In May 1969, a Holy Day Mass was disrupted by protesters in support of the Black Student Union. Demands escalated into threats to begin an anti-recruitment drive to convince African Americans not to attend the college.

In November, with an off-campus African American cultural center a primary demand, angry students barricaded themselves inside Henion Hall. When students involved in the protest were expelled, an estimated one hundred protesters from across the Midwest converged on Dubuque. Seven hours of negotiations led to the students being readmitted to the college under probation. On November 18, 1969, the student body voted "no confidence" in the administration.

Efforts to calm the tense racial atmosphere in Dubuque led the Iowa Civil Rights Commission on December 28,1969, to investigate charges that African American students had been beaten and were carrying weapons in self-defense. In 1970 Dwight BACHMAN became Dubuque's first civil rights director.

Racial strife in the 1970s included the resignation of the president of the UNIVERSITY OF DUBUQUE after he announced plans to establish a "Culture Center for African American students on campus. William G. CHALMERS stated that racist attitudes among some members of the college administration, students and community had "built to crisis proportions." (74)

Black residents of Dubuque suffered along with the rest of the city during the economic crisis from 1970-1983. By 1983 of the twenty black employed by Deere and Company in Dubuque, only five were still there. (75) In many instances, black hired through Affirmative Action in the 1970s lack seniority and were laid off in the 1980s. Other African Americans asked to be transferred to cities with higher black populations. (76)

African American students attending the UNIVERSITY OF DUBUQUE in 1973 were angered by the suspension of A. J. Stovall, a student accused of assaulting a university official during an argument over a check. African American students demonstrated by blocking the passage to some classes. Stovall was reinstated after a hearing board determined that the administration had violated his due process.

In December 1982, an estimated two hundred fifty protesters marched through Dubuque demanding that city officials work harder to guarantee equal rights. The protest was a response to several incidents. A cross was burned into the lawn of an African American family and alleged discrimination occurred at the DUBUQUE PACKING COMPANY against Asians, older workers and African Americans.

In 1983 Pierre BANDA, a citizen of Malawi, was elected president of the Loras College senate. The same year tensions rose over the appointment of Clarence W. "Rainbow" DUFFY, associated with the LITTLE DUBLIN NEWS, to the Human Rights Commission.

On April 1, 1988 a cross was burned on the north side of Dubuque. (77)

An announcement was made in December 1989 of plans to establish the 2,00lst chapter of the NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE (N.A.A.C.P.) in Dubuque. Ralph Watkins, University of Dubuque minority counselor, was the interim president. As one of its first activities, the group sponsored a Martin Luther King essay contest in the area schools. The group found support and guidance from many local residents including Ruby SUTTON, Hazel O'NEAL, Gail WEITZ, and Brian BEEKIE.

On October 23, 1989 Raymond and Cynthia Sanders found a charred cross in their garage. An inscription read, "KKK lives." The Sanders had been involved in establishing the local chapter of the NAACP. Mayor James BRADY stated that this was caused by a lack of racial diversity. (78)

In 1989 the Constructive Integration Task Force, composed of leaders from business, religion, education, and cultural activities, submitted a plan to begin integrating Dubuque. Entitled "We Want to Change," the goal was to bring one hundred minority families to Dubuque by 1995. (79) At the time, there were a little more than 300 African Americans living in Dubuque, a city with a population of more than 58,000. (80) The plan stated that it was not written to replace competent workers already in a position with "a person of color."

It is not the preferential employment of incompetent

candidates or applicants of inferior quality, but it

is the aggressive recruitment and employment of highly

and productive applicants of color for new positions or

for openings in existing positions. This this way we

will be alleviating the unnecessary fear of employees

that they will lose their present jobs to people of

color. (81)

The city's Human Rights Commission signed on, the City Council endorsed it 6-1, major employers lent support, and local colleges offered free master's degrees to minority teachers who would relocate. (82)

Reaction to the task force was strong. Unemployment at the time was 10 percent, the highest in the state. More than 4,000 union workers were furloughed at the JOHN DEERE DUBUQUE WORKS. (83) Debate developed over whether there was too much emphasis on filling a quota. The nine-page integration plan was revised and consolidated to a one-page mission statement in which the objectives were stated as promotion and enhancement of cultural diversity. (84)

Despite the fact that the city modified the proposal so that no public monies were required, the issue of encouraging minority population growth in Dubuque led to violence. On October 24, 1991 threatening racial messages were painted on the walls and doors of CENTRAL ALTERNATIVE HIGH SCHOOL. (85) Cross-burnings occurred. On November 12, 1991 the eighth cross burning since July occurred across the street from 2239 Central, and a brick was thrown through the window. (86) Agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (F.B.I.) were already in town after five burned crosses were found on White Street. (87) Uniformed police officers stood guard at DUBUQUE SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL after racial fights broke out. (88) An appearance on November 6, 1991 on "Donahue," a national television program, was made by Dubuque residents on both sides of the issue. (89)

Governor Terry Branstad stated his plans to attend an ecumenical Thanksgiving service. (90) L. Douglas Wilder, governor of Virginia, came to local church services with a victim of vandalism. Active Students Against Prejudice staged a march opposing racial incidents on November 23, 1991. When Rev. Thomas Robb, national director of the Ku Klux Klan, arrived in Dubuque on November 30, 1991 and staged a demonstration in front of the DUBUQUE CITY HALL, a counter-demonstration in Washington Park was arranged by the NAACP. Tom Churchill and Rita Daniels-Churchill organized a group called Dubuque Citizens United for Respect and Equality CURE. (91) Members of the Guardian Angels arrived in Dubuque from New York City. They spoke to students at HOOVER ELEMENTARY SCHOOL and supported civil rights efforts underway in the community. (92)

Dubuque became the first city in Iowa to actively promote racial and cultural diversity. In 1992 a number of concerned private citizens created the Dubuque Council for Diversity which replaced the Constructive Integration Task Force. In July Karmen Hall Miller was named its first executive director. (93) Concern for racial tension led the Dubuque Federation of Labor leadership to ask the Labor Center, a non-profit educational organization affiliated with the University of Iowa, to conduct a workshop on racism and bigotry for its members. (94)

Efforts to improve racial harmony continued. In 1994 the Dubuque Community Advisory Panel was established to deal with the review of discrimination or civil rights complaints against the Dubuque Police Department. The Panel, headed by Terry HARRMANN, was formed in response to complaints of the local chapter of the NAACP that police officers were harassing black men. Through the effort of Ruby SUTTON and other community leaders, the Dubuque Council for Diversity was created to draw up plans for education, mediation services, and partnerships with national diversity organizations. There was also to be training and the establishment of a data bank for employers seeking minority employees. The DUBUQUE COMMUNITY SCHOOL DISTRICT developed its own multicultural and non-sexist plan administered by Thomas DETERMAN.

In 2013 officials of the U. S. Department of Housing and Urban Development charged that the city of Dubuque discriminated against African-Americans in the administration of its Section 8 rental assistance program. HUD's report claimed that city officials made policy changes starting in 2007 that gave white applicants preference over blacks, at a time when the public was concerned about an "influx" of minorities moving to the predominantly white city. (95)

When racial tensions erupted in 2009, the report said, and city officials took even more aggressive steps to favor whites over blacks in awarding vouchers. The city reduced the number of vouchers from 1,076 to 900, eliminated a preference for very low-income residents and emptied its waiting list of hundreds of applicants. The changes had the impact of favoring applicants from Dubuque or elsewhere in Iowa, which is 91 percent white, while denying benefits to blacks from Chicago, who had been among the most frequent applicants. (96)

City officials claimed the changes were to answer funding concerns about the program, and to improve its administration. The review, however, said it found no evidence to back up those claims, and that the policies "were designed to change the racial composition of the Section 8 waiting list and program admissions." The black population in Dubuque more than tripled from 2000 to 2010 is was equal to four percent of the population.

Officials of the City knew the numbers of persons

applying to the program from outside of Iowa were

from Chicago, and were disproportionately African

American, and took the foregoing actions with the

intent to limit the ability of these applicants to

participate in the program so as to address City

residents' discriminatory perceptions on crime and

race." (97)

In April 2014, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) announced an agreement with the city of Dubuque that settled allegations that the city discriminated against African Americans applying for the Housing Choice Voucher Program.

Under the terms of the agreement, Dubuque eliminated

its residency preference system, and will submit any

future changes to its Housing Choice Voucher distribution

to HUD for review and approval. In addition, the City

agreed to undertake outreach activities to under-served

populations, meet increased and expanded reporting

requirements, comply with additional oversight from HUD,

and obtain fair housing training for core city employees. (98)

In October, 2014 claims of racial profiling by the police department made the news. City council member Lynn SUTTON remarked that,"... name, date, location and time are some of the facts we need." I'm always concerned when allegations are made, and more concerned when people won't step forward to alleviate the situation." (99)

INCLUSIVE DUBUQUE was established in 2013 to advance justice and social equity in Dubuque. (100) A fact-finding project in early 2015 revealed the following statistics: (101)

Census data from 2009 to 2013 collected by Inclusive Dubuque

shows Dubuque's black and Latino populations exceed state

averages for the percentage of residents who are unemployed

and living below the poverty level.

The city's black population increased by 229 percent from 2000

to 2010, and 5 percent of the city's residents now are black.

But the city's median income for white households is more than

double that of black ones, and black residents are almost three

times as likely to be unemployed.

Statewide, 36.8 percent of black households live below the poverty

line, compared to 52.5 percent of black Dubuque households, the data

show. The employment rate of black residents in Dubuque is 16.9 percent.

See: Category--African American See: Category--Civil Rights

---

Source:

1. Chaichian, Mohammad A. White Racism on the Western Urban Frontier-Dynamics of Race and Class in Dubuque Iowa (1800-2000), Trenton NJ: Africa World Press, Inc. 2006, p. 58

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid. p. 60

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid. p. 61

6. Oldt, Franklin T. The History of Dubuque County, Iowa. Chicago: Western Historical Company, p. 395

7. Chaichian, p. 75

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid. p. 82

11. Ibid. p. 85

12. Ibid. p.86

13. "Free Blacks Coming North," Dubuque Herald, April 23, 1861, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18610423&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

14. "All for the (Word Removed)," Dubuque Herald, March 16, 1862, p 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18620316&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

15. Google News Archive Search of the Dubuque Daily Herald.

16. "Editorial," Dubuque Herald, April 5, 1863, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18630405&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

17. Ibid.

18. "Happy Are We, Darkies. So Gay," Dubuque Democratic Herald, September 10, 1864, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=A36e8EsbUSoC&dat=18640910&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

19. "Street Lamps Opaque," Dubuque Democratic Herald, December 17, 1864, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=A36e8EsbUSoC&dat=18641217&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

20. "A Black Broker," Dubuque Democratic Herald, October 15, 1864, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=A36e8EsbUSoC&dat=18641015&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

21. "The Charity of Color," Dubuque Democratic Herald, December 15, 1864, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=A36e8EsbUSoC&dat=18641215&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

22. "Negro Suffrage Tonight," Dubuque Herald, September 13, 1865, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18650913&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

23. "The Negro Suffrage Fizzle," Dubuque Herald, September 13, 1865, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18650913&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

24. "Commendable Sympathy," Dubuque Daily Herald, September 28, 1866, p. 3. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=_OG5zn83XeQC&dat=18660928&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

25. "Helping the Blacks," Dubuque Daily Herald, September 30, 1866, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=_OG5zn83XeQC&dat=18660930&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

26. "Struck for Wages, Dubuque Herald, July 24, 1866, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18660724&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

27. "Negro Crews Coming," Dubuque Herald, July 31, 1866, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18660731&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

28. "A Black Floater," Dubuque Herald, August 12, 1866, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18660812&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

29. "Shades Departing," Dubuque Herald, December 6, 1865, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18651206&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

30. "White and Black Strikes," Dubuque Herald, September 27, 1866, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18660927&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

31. Ibid.

32. "To the Editor of the Dubuque Herald," Dubuque Herald, December 29, 1865, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18651229&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

33. "A Colored Petition," Dubuque Herald, February 2, 1866, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18660202&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

34. "A Branch of the Freedman's Bureau," Dubuque Herald, March 7, 1866, p. 4. Online:https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18660307&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

35. "A Time Line of Iowa's Civil Rights History," Online: http://www.cityofdubuque.org/DocumentCenter/Home/View/1178

36. "An Incipient Rebellion," Dubuque Herald, September 22, 1872, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18720922&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

37. "Caught on the Fly," Dubuque Herald, January 31, 1873, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18730131&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

38. "A Colored Juror," Dubuque Herald, April 29, 1873, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18730429&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

39. "An African Departure," Dubuque Herald, May 5, 1873, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18730506&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

40. "A Colored Party," Dubuque Herald, February 15, 1873, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18730215&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

41. "A Colored Knot," Dubuque Herald, July 1, 1873, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18730701&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

42. "Caught on the Fly," Dubuque Herald, August 24, 1873, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18730824&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

43. "International Organisation of Good Templars," Wikipedia. Online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Organisation_of_Good_Templars

44. "Caught on the Fly," Dubuque Herald, June 13, 1875, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18750613&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

45. "Caught on the Fly," Dubuque Herald, July 14, 1875, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18750714&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

46. "Meeting of Colored Citizens," Dubuque Herald, July 22, 1875, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18750722&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

47. Chaichian, p. 93

48. "Emancipation Day," Dubuque Herald, July 11, 1873, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18730711&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

49. Chaichian, p. 91

50. Ibid. 102

51. Ibid. 103

52. Ibid., p. 64

53. Chaichian, p. 172

54. Ibid.

55. Ibid.

56. Ibid.

57. Ibid., 64

58. "Negro Athletes Are Making Good," Spokesman-Review (Spokane, WA), July 15, 1918, p. 33. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1314&dat=19160715&id=MeMUAAAAIBAJ&sjid=suADAAAAIBAJ&pg=6585,655326&hl=en

59. Chaichian, p. 105

60. Ibid.

61. Ibid., p. 107

62. Ibid., p. 173

63. Ibid.

64. Ibid. p. 175

65. Thimmesch, Nick. "Baseball Boobery," Lodi News-Sentinel, October 10, 1978, p. 6. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2245&dat=19781010&id=1JQzAAAAIBAJ&sjid=QDIHAAAAIBAJ&pg=6905,4267876&hl=en

66. Ibid.

67. Rosie the Riveter National Historic Park (California) National Park Service

68. Ibid.

69. Ibid.

70. Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial (California), National Park Service

71. Landry, Peter. "In Dubuque, Racism Fed By Backlash Over Plan," Philly.com Online: http://articles.philly.com/1991-12-09/news/25810975_1_racial-melee-dubuque-black-couple

72. "Civil Rights," The Miami News, April 4, 1962, p. 9A. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2206&dat=19620404&id=JJMzAAAAIBAJ&sjid=aOkFAAAAIBAJ&pg=1847,1329158&hl=en

73. "Negro, Iowa College Students Exchange," The Sunday Times (Spencer, Iowa), April 3, 1962, p. 3. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2350&dat=19620403&id=v3wpAAAAIBAJ&sjid=O_4EAAAAIBAJ&pg=3543,122046&hl=en

74. Chaichian, p. 62

75. Ibid., p. 64

76. Ibid. p. 65

77. Wanamaker, Dave. "Dubuque: Diversity/Healing" Julien's Journal, January 1993, p. 29

78. Feagin, Joe R., Vera, Hernan, Batur, Pinar. White Racism: The Basics, New York: Routledge, 2001, p. 39

79. Wanamaker, p. 29

80. Ibid.

81. Ibid.

82. Landry

83. Ibid.

84. Wanamaker. p. 30

85. "Cross Burning Sentence Given," The Daily Reporter (Spencer, Iowa), July 29, 1992, p. 2. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1907&dat=19920729&id=uF0rAAAAIBAJ&sjid=89kEAAAAIBAJ&pg=1646,3931069&hl=en

86. Webber, Steve. "Hate Crime," Telegraph Herald, November 12, 1991, p. 1

87. Ibid.

88. Wilkinson, Isabel. "Seeking a Racial Mix, Dubuque Finds Tension," New York Times, Nov. 3, 1991, Online: http://www.nytimes.com/1991/11/03/us/seeking-a-racial-mix-dubuque-finds-tension.html

89. Ibid., p. 29

90. "Racial Tension Smolders in City Once Tagged 'Selma of the North': Integration: Plan to Bring more Minorities to Dubuque, Iowa, Has Triggered Confrontation and Cross-Burnings," Los Angeles Times Nov. 24, 1991, Online: http://articles.latimes.com/1991-11-24/news/mn-133_1_integration-plan/2

91. Ibid.

92. Lyon, Randolph. Personal experience as a teacher at Hoover.

93. Wanamaker, p. 31

94. Chaichian, p. 179

95. The Associated Press. "Feds: Dubuque had Bias against Blacks in Housing," Times-Republican, June 22, 2013, Online: http://www.timesrepublican.com/page/content.detail/id/561337/Feds--Dubuque-had-bias-against-blacks-in-housing.html?nav=5005

96. Ibid.

97. Ibid.

98. "Dubuque, Iowa Officials Admit To Housing Discrimination Against Blacks," WQOK FM HipHopNC.com Online: http://hiphopnc.com/5509787/dubuque-iowa-officials-admit-to-housing-discrimination-against-blacks/

99. Petrus, Jillian. "Dubuque Racial Profiling Debate Gets Heated at Public Meeting," KCRG.com Online: http://www.kcrg.com/news/local/Dubuque-Racial-Profiling-Debate-Gets-Heated-at-Public-Meeting-162165105.html

100. Barton, Thomas A. "Diversity Spawns Push for Equity," Telegraph Herald, September 27, 2015, p. 1

101. Ibid., p. 6A