Encyclopedia Dubuque

"Encyclopedia Dubuque is the online authority for all things Dubuque, written by the people who know the city best.”

Marshall Cohen—researcher and producer, CNN

Affiliated with the Local History Network of the State Historical Society of Iowa, and the Iowa Museum Association.

POVERTY

POVERTY. The first definition of the word "poverty" in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary reads "the state of one who lacks a usual or socially acceptable amount of money or material possessions." (1) The federal government has established poverty thresholds and poverty guidelines. (2) Special groups have also attempted to derive their own definition of "want." As long ago as the sixth annual meeting in Dubuque of the Iowa Union Ex-Prisoners of War Association, members discussed the progress made in helping destitute and disabled soldiers. At that time, ninety-one members of the association were too poor to pay the one dollar annual dues and many lived in poor houses. The problem existed with the pension law which required a former soldier to prove their deteriorated health was due to their confinement. Some progress had been made in Congress with the help of local representatives and senators. (3) The word continues to be defined. One of the better definitions is found later in this entry.

The first efforts to provide some degree of care for the destitute came as early as 1848 with the establishment of a POOR FARM outside the City of Dubuque. This marked perhaps the first "large scale" local governmental attempt to deal with those in need.

In 1908 "The Conquest of Poverty" by Dr. Frank Julian Warne studied the role played by labor unions in reducing poverty. He stated his belief that the primary cause of poverty was not individual or social defects in character, but the economic factors over which the individual had no control. He made the claim that it was chiefly due to unions that poverty was reduced by their regulation of factory management, provision of safety equipment, and the enforcement of better sanitary conditions. Warne quoted John Mitchell, ex-president of the United Mine Workers, as saying unions secured for workmen a wage sufficient to live in a manner confortable to American standards. He continued that unions had also accumulated large funds to assist workers and their families affected accident, death, sickness or unemployment. In 1908 not less than $5,000,0000 had been paid for the relief of unemployed workmen not including millions of dollars in strike and lockout benefits. James Duncan, first vice-president of the American Federal of Labor, pointed to union success in reducing hours per day improving the health of the workers. (4) Members of Dubuque's Machinist and Aerospace Workers Local 1238 adopted a resolution in 1973, for example, supporting minimum wage laws passed by both houses of Congress raising the minimum to $2.00 immediately and $2.20 in 1974. (5)

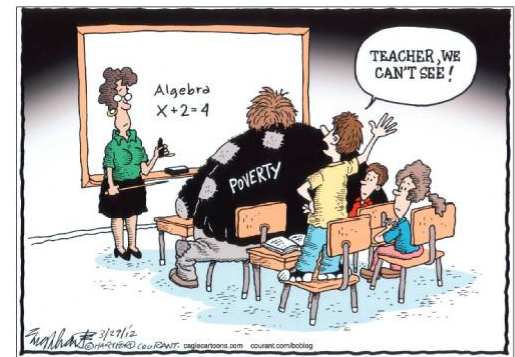

The effects of poverty on the young have often been studied. Persistent poverty during the first five years of life, research has shown, left children with IQs lower at age five than children who suffered no poverty. Greg J. Duncan of the University of Michigan found that persistently poor children were more likely to exhibit behavior problems. Every year they lived in poverty also significantly increased their risk of falling behind in school by ages 16 to 18 according to the U. S. Department of Education. (6) In 2004 an Iowa study suggested that Iowa taxpayers could gain from investing in early childhood education programs. A report from the Des Moines-based Child and Family Policy Center suggested early childhood education would offer a "substantial payoff"---as much as three dollars for every dollar invested, instead of paying later for remedial and special education, criminal justice, and welfare benefits. (7)

The GREAT DEPRESSION resulted in the election of Franklin Roosevelt who wasted no time in changing the federal government's role in relieving poverty. In addition to the many "alphabet agencies" created to put people back to work, the Federal Emergency Relief Act of 1933 provided direct grants to states to help relieve unemployment. The Social Security Act was signed by him on August 14, 1935. Old age insurance was limited to about 60% of the labor force at the beginning. This grew to 90% of all people working in 1966. In addition, 90% of the children and their mothers were eligible for monthly benefits if the family wage earner died. (8)

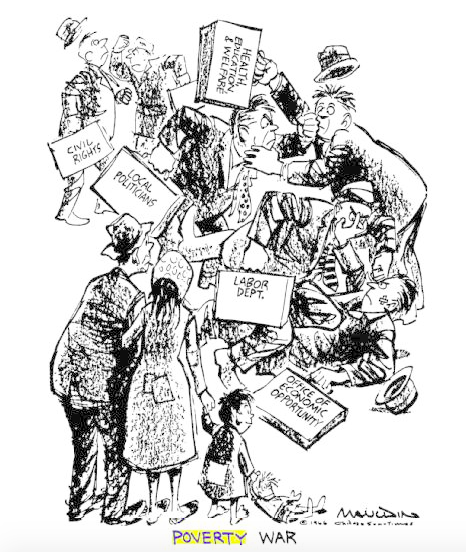

On January 1, 1964 President Lyndon Johnson vowed an "unconditional war on poverty in America". He described his budget

as efficient, honest, and frugal maintaining the full strength

of our defenses while providing the most federal support in

history for education, for health, for retraining the unemployed,

and for helping the economically and physically handicapped.

On January 31, 1964 as part of the "War on Poverty," President Lyndon Johnson called for a permanent food-stamp program. The program was intended to strengthen the agricultural economy and provide improved levels of nutrition among low-income households. The program began operating nationwide in 1974. The expense of the program led to cutbacks in the early 1980s, with incremental increases in the latter half of the 1980s due to the domestic hunger problem. Although the Food Stamp Program was renewed in the 1996 Farm Bill, changes that affected Dubuque residents included: (9)

denying eligibility for food stamps to most legal

immigrants who had been in the country less than

five years;

placing a time limit on food stamp receipt of three

out of 36 months for Able-bodied Adults Without

Dependents (ABAWDs) who are not working at least 20 hours a week

or participating in a work program;

reducing the maximum allotments to 100 percent of the change in the

Thrifty Food Plan (TFP) from 103 percent of the change in the TFP;

freezing the standard deduction, the vehicle limit, and the minimum

benefit;

setting the shelter cap at graduated specified levels up to $300 by

fiscal year 2001, and allowing states to mandate the use of the

standard utility allowance;

revising provisions for disqualification, including comparable

disqualification with other means-tested programs; and requiring

states to implement Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) before

October 1, 2002.

The Food Stamp Program was renamed Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in 2008. States were allowed under federal law to administer SNAP in different ways. (10)

In 1965 the new Social Security Medicare law offered "medical assistance for the aged" as well as health benefits to regular recipients of public assistance (welfare). The free fare was financed by the U. S. Treasury and the states. In some instances, counties and local communities also provided funds. All but six states--Alaska, Georgia, Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio, and Texas--put into effect programs for the "medically indigent," those persons older than 65 or poor enough to receive regular welfare checks but unable to afford their sick bills. Programs varied from state to state with all providing some hospital care. Some covered certain doctor bills, some drugs, some care in a nursing home or the patients own home and even eyeglasses or false teeth. Eligibility rules and ceiling on assets differed. States were encouraged by the federal government to drop fixed income ceilings and to determine need only by income "actually available." Children could not be required to pay for their parents' care, however, a state could place a claim against property to get its money back when a person died. (11)

Effective January 1, 1966 the same benefits for "medically indigent" over 65 could be extended by a state to those under 65 who would ordinarily have qualified for welfare except that they were not sick and their assets exceeded the ceilings. This included children under 21, the blind, and those totally and permanently disabled. By January 1, 1970 minimum standards would apply to all welfare-type, free-care programs. Every state implementing a program would have to offer some hospital benefits, some nursing-home care, some laboratory and x-ray services, and some coverage of medical bills. Extra benefits could be added. (12)

In 1966 'Upward Bound' funds were offered to America's colleges and universities as a way of helping talented and yet potential dropout sophomores and juniors seeking college. Those selected were invited to a college campus during the summer for an eight week program of academic and social preparedness. During the year, colleges offered the students in high school tutoring. (13) Upward Bound students from Dubuque were still benefiting from the program at the Northeast Iowa Community College in 2006 as an article in the Telegraph Herald on June 29, 2006 described.

R. Sargent Shriver, director of the War on Poverty told those attending a conference in Des Moines that there was five times as much money available in 1966 as there was in 1965 for anti-poverty programs. It was up to the local leaders to come to the federal government with proposals. He encouraged consideration of Project Head Start which had 761,000 children involved in 1965. Job Corps had 500 graduates of which 20% had returned to school, 35% had gone into the military, and most of the rest were supporting themselves for the first time. (14)

In November, 1965, regulations threatened Dubuque anti-poverty proposal. Money from the Federal Office of Economic Opportunity depended upon the appointment of a full-time director for the Dubuque office; organizing the Dubuque agency so that one-third of the members were from the group (poor) being served; establishing by-laws for the organization; and providing an acceptable 10% grant by the city for a poverty study. A grant of $26,031 to finance a study of poverty in the county as the first step in the anti-poverty program had been expected since the application was filed in July. The Dubuque Area Economic Opportunity Agency (DAEOA), however, learned that several parts of their application were unacceptable including the need to certify the value of several donations. (15)

At a November meeting of AFRICAN AMERICANS living in Dubuque, the conclusion was reached that problems of civil rights and poverty were so closely related that it was difficult to separate them. Those in attendance agreed that blacks were discriminated against in jobs and in housing. Secretary of the Dubuque Area Economic Opportunity Association and City Manager Gilbert D. CHAVENELLE assured those in attendance that the organization would not limit itself to those whose incomes were less than $3,000. He maintained that it was up to all those on the committee to solve the problems. The immediate aim was helping children and getting the male adult more training. (16)

A "Poor People's March" was held in Dubuque on May 18, 1968 in support of a similarly themed march in Washington, D. C. Participating despite a steady rain, an estimated two hundred fifty people marched six abreast from 12th Street to Main, Main to Seventh and Seventh to WASHINGTON PARK where a rally was held. Reverend Thomas RHOMBERG spoke asking why there was no low-cost housing in Dubuque except substandard which should be torn down, why the churches were so withdrawn from the issue, and why public officials admitted they knew nothing about public welfare?

The same month Governor Harold Hughes and a "task force" of eight state officials visited Dubuque. Without offering money of which he said, "We have no money," Hughes believed the state could help cities fight poverty. He attacked his own government's lack of aid to the poor especially for housing. "This is supposed to be a state resource council, but we have no resources for you." He also criticized Iowa law requiring referendums before public housing could be built. State welfare laws, he believed inhibited rather than enhanced good housing by subsidizing rent in unfit dwellings. He also asked for stricter code enforcement. (17)

Hughes recommended a fight against poverty featuring five fronts: camping, recreational and cultural experiences, youth employment and education, adult employment, and vocational training with student assistance. Concerning camping, Hughes remarked,"It's a great experience to get outdoors and to feel close to God." He supported churches bringing under-privileged children to their camp while avoiding taking just one child who would be a "helpless minority." School grounds should be kept open after hours for recreation. "Let them hit a golf ball or two and see how the other half lives." Affluent Dubuque residents should, he believed, give under-privileged children free rides over the city in their planes. Employers, Hughes went on, should by private subscription create more jobs. "When you take away the pride of the male member of the family through the loss of hope, you immediately begin the disintegration of his children and grand-children. Mayor Michael Sylvester MCCAULEY later announced that the Social Action Commission of the Dubuque Council of Churches would meet with interested citizens to discuss the results of Hughes' task force visit. (18)

Students at the UNIVERSITY OF DUBUQUE and residents of the city were recruited in 1967 and 1968 for Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA). A federal government-sponsored volunteer organization, VISTA worked at eliminating poverty in the United States and its territories. Volunteers were needed to teach, work in hospitals, or with athletics or recreational programs. Paid $75 each month plus room and board, the volunteer lived with the poor in ghettos, on Indian reservations, or with migrant workers. VISTA was funded to have 4,300 volunteers in service at a time. There were between 45,000 to 50,000 others whose applications had been accepted and were waiting their turn. Iowa had 87 counties where poverty was above the national average. It was expected, however, that the state would only receive twelve workers. (19)

The commissioner of the Iowa Department of Social Services in 1969 praised private welfare agencies for "assuming leadership of social services to Iowa's needy." Speaking to the board of directors of Hillcrest Services to Children and Youth, he declared,"I don't know what would happen to social services in Iowa without such private agencies at Hillcrest." The state agency, he claimed, was limited by guidelines to those 40-50 years old and lacking finances to keep pace. He criticized the state's program as "meager," due to "our affluent society which is not sympathetic to the problems of humanity." He continued "we spent our money in paperwork and writing fancy brochures telling who is and who isn't eligible to receive welfare instead of spending the money...on the needy." (20)

In 1971 the nineteen Dubuque, Delaware, and Jackson county senior citizens' clubs funded by the River Valley Community Action Program (CAP) were required to account for their activities to determine their future in the federal poverty program. The evaluation conducted by the Tri-County Senior Citizens' Council included club memberships, past accomplishments, projected goal and priorities for the coming year and the leadership efficiency of their officers. The audit was caused in part by the Table Mound Club leaving CAP after the president admitted that his club did not consider a health, education and nutrition center an immediate priority. (21)

A U. S. Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs in 1973 found that only a small percentage of the poor in the tri-state area were receiving federal food assistance. One of the best results in the region came from Dubuque County which had 11% of its population ranked "poor" with only 36% of them receiving food stamps. (22)

Dubuque City Councilman Emil "Mike" STACKIS in 1975 proposed spending federal Community Development funds to help low-income family pay their monthly utility payments. Working with city personnel, he distributed handouts to the other council members explaining a "utility assistance program." Under his plan, a family would be eligible for utility assistance if its total income did not exceed 25% of the median income of the Dubuque area as determined by the U. S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. A family of three would be eligible if its income did not exceed $3,175 annually, a family of five would be eligible if its income was below $3,825 annually, and a family of eight would receive benefits if its income was below $4,650. Payments would subsidize costs of heat, electricity, water, sewer, and refuse collection. Money would be distributed according to the number of bedrooms. A two-bedroom dwelling would receive $39.32 monthly, a four bedroom dwelling would receive $62.40, and a six-bedroom dwelling would qualify for up to $75.60. (23)

In January 1982, the first distribution of surplus cheese was made in Waterloo with social services officials finalizing plans for the Dubuque area into which an estimated 36,000 pounds of cheese was expected. Assistance was asked from food pantries and religious organizations which had systems in place. Federal income requirements and allocations were: (24)

Five pounds--families from 1-3 people. A single person had to have a gross

income of $664 a month or less; two people, $878; three, $1,090

Ten pounds--families of four, gross income of $1,303 or less; five, $1,516;

six, $1,728

Fifteen pounds--families of seven, gross income of $1,941 or less; eight,

$2,153; nine, $2,366

For an additional three people, add another five-pound sack of cheese. To

calculate eligibility, add $213 for each additional child.

In 1984 the City of Dubuque pointed to many organizations aimed at improving people's lives: (25)

OPENING DOORS offering hospitality and opportunity to women, alone, or with children who need emergency/transitional housing and related support services/

Dubuque Circles Initiative which was part of an innovative national

movement that connected volunteers and community leaders to families

wanting to make the journey out of poverty

HILLS & DALES CHILD DEVELOPMENT CENTER dedicated to building meaningful lives for individuals with disabilities by offering services support to the whole person and enhance community inclusion.

PROJECT CONCERN dedicated to the basic needs of families so that they can remain in their homes and to all homeless individuals and families so that they will be self-sufficient.

Mentor Dubuque worked to improve the lives of youth by providing

friendship, support and role modeling through volunteer mentors.

Reach & Rise, a national YMCA program, designed to build a better

future for youth by helping them reach their full potential

through the support of caring adults.

FOUR MOUNDS preserving the natural, architectural, and historical resources of the Four Mound estate while educating with hands-on opportunities for youth and our community.

St. Mark Youth Enrichment supporting the education and social

social needs of school-aged youth and their families.

American Red Cross preventing and alleviating human suffering

in the face of emergencies by mobilizing the power of

volunteers and the generosity of donors.

Members of the DUBUQUE COMMUNITY SCHOOL DISTRICT board of education voted in January 1991 to consider offering a breakfast plan for students who qualified for free or reduced-price lunches. Factors in endorsing the plan (which was approved) included findings that hungry children were two to three times more likely than children from non-hungry low-income families to have suffered from individual health problems including fatigue, irritability and inability to concentrate. Children who reported a specific health problem were absent from school almost twice as many days than those not reporting specific health problems. (26)

In 1992 Dubuque had a Bread for the World chapter. Along with covenant churches and individuals, the organization was involved in a grassroots campaign to write legislators on behalf of hungry and poor children in the United States. The Dubuque chapter met monthly to mobilize Christians, Jews and others for the funding of three key programs: The Special Supplemental Food Program for Women, Infants, Children (WIC), Head Start and Job Corps.

The WIC program supplied additional food to women and assisted them in budgeting, nutrition and medical referrals. According to Reverend Norman WHITE, rural life director of the ARCHDIOCESE OF DUBUQUE, the U. S. Department of Agriculture claimed that for every dollar spent in helping pregnant women in the WIC program, there was a 'Medicaid savings of between $1.77 to $3.13 for the mother and baby during the first sixty days of the baby's life." The General Accounting office estimate that WIC reduced the rate of low birth weights by 25%. Low birth weights contributed the deaths of newborns and high medical costs to treat chronically ill children. (27)

The critical shortage of affordable housing was identified as early as the 1980 census. In that report, the figures were noted that 70% of the downtown and north side residents were renters and 70% of the families were below the poverty level. In 1980, 80% of the dwellings in the areas lacked full sanitary facilities and 88% were constructed before 1940.

Confronted in 1990 with a subsidized-rent waiting list, home demolitions for redevelopment, and deteriorating north-side housing stock, the Dubuque Housing Commission appointed a community task force to deal with the problems. The task force was charged with defining the city's affordable housing needs, recommend a replacement policy for housing lost to development, develop a plan to assist people relocating because of development, and to explore the possibility of a neighborhood-based housing development corporation. In 1990 the wait for subsidized housing was 1-3 years, classified ads routinely listed less than 100 vacancies citywide, and only 235 homes were listed by the Board of Realtors Multiple Listing Service. Of these, only 102 were in the "affordable" range of around $42,000. (28) Related to suitable housing was the seasonal need for the elderly and very young to escape excessive heat during the summer. "Cooling" stations were established by the city and private organizations. In 2018 the number had grown to include the CARNEGIE-STOUT PUBLIC LIBRARY, MYSTIQUE COMMUNITY ICE CENTER, DUBUQUE RESCUE MISSION, and the MULTICULTURAL FAMILY CENTER. (29)

April 25, 1994 marked the opening of Dubuque's second Habitat for Humanity house for someone who otherwise could not afford it. Habitat for Humanity, a Christian housing ministry, nationally built and renovated homes with the assistance of volunteers and the family for whom the house would eventually belong. The "sweat equity" of the future owner in the home allowed the organization to then sell the house to the new owner interest-free. There were over fifty requests for applications on a waiting list which only needed volunteers and money to fill. (30)

The City of Dubuque hired Cindy Steinhauser, the current DUBUQUE MAIN STREET, LTD. director and Pam Myhre-Gonyier, a part-time associate planner for the city, in December, 1994 to serve as neighborhood specialists. Their job was to help neighborhoods confront such problems as crime, poor housing, lack of child care, and recreation for older children. This would be done by helping to organize neighborhood groups, providing leadership training to residents, and better coordinating city services. (31)

HOPE HOUSE was opened in Dubuque in 1997.

Among many activities community-wide was the "Empty Bowls" project in 2004 organized by the Teen Leadership Council, the youth philanthropy group of the Community Foundation of Greater Dubuque. At the annual Taste of Dubuque, members of the group invited those in attendance to paint a bowl with a design of their choice. The cost to paint a bowl was $2.00. After the bowls were fired by the Naked Dish, the food-safe bowls were sold at the Tri-State Chili Cook-Off with the proceeds going to fight childhood hunger in Dubuque. (32)

Several years later the "Feed the Need" silent auction and soup luncheon was hosted by the Community Foundation of Greater Dubuque and its youth grant-making board, the Youth Area Philanthropists known as "YAPPERS." Comprised of 28 students from area high schools, YAPPERS spent the year learning about community issues affecting local youth living in poverty. "Feed the Need" began as part of the Empty Bowls Project. A national youth poverty awareness campaign, the program aimed to increase local awareness, community involvement and charitable giving focused on improving the lives of Dubuque disadvantaged youth. Locally the project was sponsored by the Community Foundation of Greater Dubuque, Manna Java World Cafe, WEBER PAPER COMPANY, Theisen's, Hy-vee, Inspire Cafe, Panera Bread, and Houlihan's. (33)

The success of the YAPPERS was frequently demonstrated. In 2011 the organization distributed $2,500 to four organizations including Bridges Initiative Childcare Program ($400); Crescent Community Health Center School ($900) providing a convenient location for dental exams for children with no dental "home" or transportation to reach a dental office; Hills & Dales Safe Transitions and Accessible Childcare Program ($700); and Opening Doors Medical Needs Fund ($500) providing prevention care doctor co-pays, over-the-counter medications, head lice kits, and transportation to doctor appointments and for after-hours care. (34)

Creating awareness of a life in poverty was the goal in 2002 of OPERATION NEW VIEW and the Iowa State Extension. A 3-hour learning experience called "Exploring the State of Poverty Welfare Simulation" was conducted on November 7, 2002 at WESTMINSTER PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH. (35) Simulations appeared repetitively through 2015. Students studying social work at LORAS COLLEGE in three courses were divided into "families to participate in four, 15-minute sessions that simulated a week in poverty. Loras had used simulations for fifteen years, but in 2015 for the first time it partnered with Operation New View which facilitated poverty simulations for free in Dubuque, Jackson, and Delaware counties. Weatherization programs to insulate homes and provide energy efficient appliances if others were found unsafe was managed by Operation New View in 2003. It was expected that the number of poor taking advantage of the program would double in the year ahead. (36)

Politics were never forgotten in the arguments over what should be done. In 2005 Mark Hanson, presiding bishop of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, the fourth-largest Protestant denomination in the United States came to Dubuque. While attending a Rural Ministry Conference at WARTBURG THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY he called balancing a deficit budget by cutting the "social network" an issue of justice and fairness. He stated that he found it "perplexing" that the term "homeland security" would mean getting on an airplane safely but not ensure that a single mother's children were fed. (37)

Misreporting also proved evident. Schools receiving federal poverty aid had to demonstrate, according to No Child Left Behind legislation, annually that all students were progressing or risk such penalties as an extended school year, changing curricula, or firing administrators and staff. In 2006, the Associated Press reported that states were helping public schools escape potential penalties by "skirting" requirements that students of all races had to show academic progress. With the permission of the federal government, schools deliberately did not count the test scores of nearly 2 million students when they reported progress by racial groups. The AP found that Iowa schools were exempt from penalties in five racial categories--white, black, Hispanic, Asian and American Indian--if the number of students in any of these groups in a school was less than 30. That meant that Iowa avoided penalties in the 2003-2004 school year for tests scores of 70% of Asians, 78% of American Indian, 38% of black students, and 40% of Hispanic children according to the National Center for Educational Statistics. This affected 6% of the 254,679 Iowa students who took standardized tests. Schools also had to report scores by categories--poverty, migrant status proficiency and special education. Failure in any category meant the entire school failed. (38)

The "Bridges Out of Poverty" project begun in 2007 was a training program for people from the middle class develop a working model of what it meant to live impoverished, middle class or wealthy lifestyles, and the hidden rules of getting ahead in society. The "Getting Ahead in a Just Gettin' By World" program was planned to help low-income families develop a path to stable, secure lifestyles by understanding the hidden rules of class. "Bridges" defined "poverty" as being without resources more than being without money. Resources included: (39)

Financial--having the money to buy goods and services

Emotional--being able to choose and control emotional

responses to negative situations

Mental--having the abilities and acquired skills to

deal with daily life

Spiritual--believing in divine purpose and guidance

Physical--health and mobility

Support systems--resources available in times of need,

such as friends and family

Relationships/role models--access to adults who are

nurturing and do not engage in self-destructive

behavior

Knowledge of hidden rules--knowing the unspoken cues

and habits of a socioeconomic group

In 2010 the Circles Initiative was the final stage of the Bridges Initiative. This campaign was to change communities by building relationships across class lines that inspired and equipped people to end poverty. (40) A "circle" involved a family working to get out of poverty and two to four community "allies" who were Getting Ahead graduates willing to befriend the family and support their way out of poverty. Circles was sponsored by the Family Self-Sufficiency office of the Dubuque Housing and Community Development Department. Rather than mentoring, Circles was designed as an informal two-way relationship where everyone involved learned from each other. Getting Ahead graduates receiving a $20 stipend each week for attending class were the "poverty experts." (41) Their experiences informed others of circumstances that kept them in poverty. (42)

Between 2007 and 2011 an estimated 2,500 people attended the "Bridges Out of Poverty" classes in Dubuque. This included people from Sioux City because the Dubuque program was the first of its kind in Iowa. The Getting Ahead program graduated 144 Dubuque residents. The Circles project was overseen by Move the Mountain which monitored and provided assistance to local initiatives. "Allies" tended to be retired whites; it was hoped that younger people and minorities would make up a larger proportion. Getting Ahead graduates were generally AFRICAN AMERICANS. (43)

In 2011 city officials received the 2010 Quantitative Research Study on Crime and Poverty in Dubuque. Directed by the Northern Illinois Center for Governmental Studies, the study looked at Section 8 subsidized housing which was generally found in the downtown and eastern portions of the city. The conclusion was that the relationship between crime and subsidized housing was more about crime and poverty than it was participation in a housing plan. Among the findings were that city officials and police in Dubuque were using stricter eligibility and termination requirements to keep voucher holders accountable. Among criminal grounds for termination were disturbing the peace, disorderly conduct and interference with official acts. Deferred judgments were given the same weight as convictions and juvenile offenses counted against the lease holder. Arrest reports listing someone with "no permanent address" did not mean someone staying illegally with a Section 8 tenant. 'There are simply people who do not want to be found.' (44)

Research indicated that despite many programs, poverty remained a major factor in the lives of many Dubuque residents. In 2011, one-third of Dubuque's public school students were eligible for free or reduced-price meals with the number varying by school. In Fulton, Prescott, and Audubon elementary schools over 80% of the students were eligible. At DUBUQUE SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL one-third of the students are eligible. (45)

In the election season of 2012 the importance of helping those burdened by meeting their daily needs participate in their community gained extra importance. Referring back to the definition of poverty used in "Bridges" this meant encouraging more citizens to attend a city council meeting or voting. (46)

Independent activities continued to address poverty. On September 27, 2014 the St. Vincent de Paul Society Friends of the Poor Walk was held in conjunction with Catholic Financial Life. The walk began at MURPHY PARK and included a circuit around MOUNT CARMEL MOTHERHOUSE. Participants were asked to raise a minimum of $25 as a goal. A silent auction included hotel stays and a golf package. Proceeds supplemented the ST. VINCENT DE PAUL SOCIETY programs. The National Friends of the Poor Walk began in 2008 on the 175th anniversary of the society which believed spiritual growth came through acts of charity. In 2013 the walk was held in 232 locations across the country. The Dubuque walk in 2013 involved 300 participants and raised $10,000. (47)

While noting that a significant number of minority populations were well-educated, the need for more outreach was expressed. In 2014, 570 Dubuque high school students took an advanced placement (AP) test. Of these, 90% were white, nearly 2% were African American, and less than 1% were Hispanic. Partnering with nonprofits to promote grade-level reading and dropout-prevention initiatives, the school district received $10,000 in 2014 from the Foundation for Dubuque Public Schools to expand the district's Leadership Enrichment After School Programming (LEAP). The goal of the program was to broaden students' general educational experiences through new experiences, discovering their talents, reinforcing productive behavior and building self-confidence. In past years, LEAP was only available to students at the middle schools due to it being funded by a grant supporting the program for Title I schools. The district partnered to promote tutoring services at the DUBUQUE DREAM CENTER and the DUBUQUE BLACK MEN COALITION job-skills and leadership development program. (48)

In 2015 data from the U. S. Census Bureau showed that the percentage of tri-state area residents living in poverty continued to rise even as the country emerged from recession. Since the pre-recession year of 2007, the number of Dubuque County residents living in poverty increased 2.7% to a figure of 11.5%. From 2012-2015 Dubuque--with 3% of the state's population--saw more than 8% of all new jobs added across the state. Average wages over the period exceeded the rate of inflation by more than 15%. Higher wages, usually thought of as a means to lift low-wage workers out of poverty, actually left many in worse condition. Higher wages did not fill the gap which resulted when the employees lost federal benefits like food stamps and Medicaid or housing subsidies. The highest pay in high-tech manufacturing, engineering, or computer technology was out of reach of low-skilled workers. (49)

There had developed a disconnect between the unemployment rate and the number of people living in poverty. In 2015, Dubuque experienced an average annual job growth of about 1.6% and 3% unemployment. This, however, did not account for those unable to find full-time employment and those who had given up. Those working in fast-food and service industries earned wages leaving them unable to support their families. Following the recession, more businesses became automated with a resulting cut in employment. (50)

In 2015 INCLUSIVE DUBUQUE partnering with the city's Human Rights Department gathered information through dialogue sessions from more than six hundred residents with another 1,700 filling out a survey. (51) Among the findings was that 17% of the students in the DUBUQUE COMMUNITY SCHOOL DISTRICT were representatives of minority communities compared to 2.2% of the staff. Superintendent Rheingans noted that the District had tried a variety of ways to attract minorities, but that higher pay in Illinois, Wisconsin and Minnesota made the job very difficult. He added that education departments, especially at the UNIVERSITY OF DUBUQUE, had begun seeing more diverse enrollment and noted it was a "growing opportunity for us." Multi-cultural training had been offered beginning in 2006 by the city with its three-year Intercultural Competency Initiative. In a similar manner, the public schools had regularly used in-service days and required workshops for multi-cultural education. Working with the Dubuque Human Rights Department, lesson plans for high school and middle schools had been designed to address racial and cultural differences. (52)

Means of transportation was explored. Lack of an automobile likely meant children were unable to reach Head Start programs and workers were unable to reach jobs on the West Side. JULE (THE), it was charged, only had defined routes and did not run at each working shift. Transit officials, however, countered that changes had reduced travel times, increased coverage and extended hours resulting in record levels of ridership. According to city figures, fixed-route ridership increased an average of 25% per month since the changes. (53)

In 2016 the nonpartisan Iowa Policy Project found that in Dubuque County a single parent with two children needed to earn $21.45 an hour to meet basic needs. When supervisors met with members of the Dubuque Area Chamber of Commerce, the consensus was that increasing the minimum wage was a state and federal legislative matter. Concern was expressed that if the minimum wage were increased, employers would cut back on employees' hours and increase the price of goods and services. (54)

Programs to support low-and moderate-income families and encourage home ownership and reinvestment in downtown and neighborhoods offered upward mobility. According to a 2016 article published by Forbes.com. Dubuque, Iowa; San Jose, California; and Washington, D.C. were listed as upwardly mobile cities. The article stated that the U. S. average for people climbing from the bottom of the income scale to the top was about 7.5 percent. In Dubuque and San Jose, that figure was between 13% to 18%. (55)

Opening Doors Teresa Shelter providing housing for homeless women and children reached its capacity throughout 2017. In that year, the number of "bed nights" at the shelter was 23% higher than in 2016. All women staying in the shelter were either employed or in school, but their income was not enough. At the time the federal government defined affordable housing as 30% of a person's income. Earning minimum wage, however, did not allow a person to find a place to live that did not require between 40% or 50% of their income which was not sustainable. In Dubuque County a family of four needed $58,644 to cover housing, child care, food, transportation, health care and taxes. Child care alone in Dubuque County, rose from $778 per month in 2014 to $1,086 in 2016. (56)

Helping some people was the Housing Choice Voucher program, a federal initiative operated locally by the City of Dubuque. In 2018 the city had adequate funding to distribute an estimated 850 housing vouchers. Demand, however, outpaced the supply. (57)

Dubuque Area Congregations United in 2018 sponsored the annual CROP Hunger Walk. Following a route stretching from HOLY TRINITY LUTHERAN CHURCH to MURPHY PARK, the event served an a fundraiser for initiatives seeking to end hunger. Church World Service received 75% of the proceeds with the rest donated to the DUBUQUE FOOD PANTRY, Dubuque Rescue Mission, and People in Need which provided direct aid to people at risk of eviction or having utilities disconnected. In 2017, the event raised $14,000. (58) In addition, efforts continued by such organizations as CONVIVIUM URBAN FARMSTEAD and DUBUQUE URBAN FARM. Important to such work were contributions from the COMMUNITY FOUNDATION OF GREATER DUBUQUE.

Census data clearly indicated that advanced education was important. In December, 2018 the median wage for households was $59,150--an increase from $56,154 the previous year. Residents with less than a high school education earned a median income of $21,200, high school graduates or those with an equivalency degree earned $30,700, those with an associate's degree had a median income of $34,100 while a bachelor's degree raised the income to $45,750. Those with a graduate degree had a median income of $58,600. (59) Being new to the United States, a person can be proficient in casual conversation while deficient in the academic language needed in class. Too few ELL students attend the Dubuque public schools to report a figure, but statewide the graduation rates for ELL students and those who qualify for free-and-reduced priced meals in 2017 were several percentage points lower than the over all rate. To establish better relationships with the families of English Language Learner (ELL) students, instructors began regular home visits. In addition, in 2017 the Dubuque Community School District hired two additional ELL instructors--for a total of 12--and a Marshallese interpreter to help staff communicate with families and translate forms. (60)

The Greater Dubuque Development Corporation at the end of 2018 was taking steps to begin a pilot program in 2019 aimed at increasing the number of child care providers. This was in response to findings that child care was one of the top twenty workforce needs at the present time and into the next decade. Current child care providers were retiring or taking jobs where they could earn a better living. In 2018 the average hourly wage for a child care worker was $9.23 per hour. This compared to $9.87 for a cashier or $12.30 for a retail salesperson. GDDC planned to use an existing workforce program, Operation Dubuque, administered by the Northeast Iowa Community College, to increase the number of child care providers. To increase female participation, the program offered free child care while the students were trained and paid some child care expenses for up to twelve months after participants were hired. (61)

In 2019 a United Way study using "point-in-time data" collected in 2016 indicated that the growing financial hardships of this decade were largely confined to one category named Asset Limited Income Constrained, Employed (ALICE) but often called the "working poor." In Dubuque County, 14% of all households fell into this category in 2010. By 2014 the percentage had risen to 22%. Additionally, 11% of households were below the poverty level in 2016, up from 10% in 2010. The ALICE report challenged the idea that "getting a job" was sufficient to rise out of poverty. The report indicated that a single adult in Dubuque County needed a monthly income of $1,608. This could be earned by a full-time job paying $9.65 per hour. The ALICE study, however, found that a Dubuque County family with two adults, an infant and a pre-schooler spent $4,887 per month to meet basic needs. (62)

In March 2019, city council members reviewed the results of the 2018 Community Perceptions Survey, the second conducted by Loras College's Public Opinion Survey Center in conjunction with the Great Dubuque Development Corporation. Among the findings was that 79% of the respondents felt Dubuque was a food place to live and 75% felt Dubuque was "on the right track." Respondents overwhelmingly (96%) felt safe in their own neighborhoods, but only 51% felt safe downtown despite decreasing crime and shots fired statistics. Of the black respondents, 62% felt that race relations was the biggest challenge for Dubuque with 56% believing the community had not been responsible to race relations issues. Among all respondents, 70% agreed that diversity was beneficial to the community. Median household income results found that white residents in 2017 earned $52,346 while the median income for black residents was $14,818. It appeared from the survey that more work had to be done to make sure minority populations were aware of programs meant to assist them. (63)

In July, 2019 members of the city council approved soliciting proposals for the creation of an Equitable Poverty Prevention Plan for a maximum budgeted amount of $75,000. (64) Research indicated that in 2019 16% of the 54,940 residents in the city lived in poverty. Minority residents were significantly more likely to live in poverty than the national averages. Among AFRICAN AMERICANS in Dubuque 60% lived in poverty while the national average was 25.2%. Among HISPANICS in Dubuque, 26% lived in poverty compared to the national average of 22%. Among residents of two or more races in Dubuque, 47.6% lived in poverty which was far higher than the national average of 18.4%. The rate of white residents living in poverty was slightly above the national average. (65)

The planning process envisioned by the council would examine existing programs to determine their success. Dubuque officials could reach out to STAR communities nationally to observe their programs. STAR cities were communities thought to have made progress on sustainable planning efforts. (66) Trends and best practices would be studied and performance goals established to gauge the success of the new plan. The firm selected would study self-sufficiency, economic and employment programs, internet and computer-training programs, access to affordable housing, nutrition and CHILDREN'S MEAL PROGRAMS. (67)

The new plan followed the city's participation in Dubuque Circles Initiatives with partner organizations. That program evolved into Gaining Opportunities in 2018. The new plan would operate with Gaining Opportunities until the new plan concluded. At that time, Gaining Opportunities would change reflecting the new plan's findings and goals. (68)

To help those needing education and training, Opportunity Dubuque, a partnership of the GREATER DUBUQUE DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION (GDDC) and Northeast Iowa Community College, allowed participants to complete industry-driven certifications to upgrade their skills or begin their careers. While these courses were free of charge, child care and transportation could pose barriers. (69)

In 2019 re-districting schools to expose students to more diversity was again s subject of debate in the Dubuque Community School District. Superintendent Rheingans noted that the district focused more resources and opportunities to schools with higher concentration of need. If the district treated all elementary schools, equally would reduce that assistance. Redistricting would also effect the distribution of federal funding the district received for Title I schools. Changing the percentage of students from low-income backgrounds at individual schools would result in aid being spread between more schools reducing services to schools with greater need. (70)

The announcement was made on August 18, 2019 that Resources Unite, a local nonprofit, would be paid $30,000 to oversee the general assistance program which provided rental, utility and burial assistance to applicants who met income guidelines. Those services had been handled by staff in the Veterans Affairs office. The decision by the Board of Supervisors was passed on a 2-1 vote with confidence expressed that the Veterans Affairs staff should be completely dedicated to working for veterans. The decision was not without controversy with one supervisor concerned that the decision was simply a "pre-selected vendor" rather than give other agencies an opportunity to submit their own proposals. (71)

Operation: New View relinquished its sponsorship to administer the federally funded Head Start program in Dubuque, Jackson and Delaware counties. On August 19, 2019 it was scheduled to transfer operation to the Community Development Institute, a contractor for the U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, which would operate the program temporarily. Operation: New View had worked for months addressing the organization's financial problems. It received an estimated $2.2 million annually to operate thirteen Head Start sites in Dubuque, Epworth, Dyersville, Maquoketa, and Manchester and a 20% local match, but the local program had operated at a deficit for several years. (72)

In 2015 Caprice Jones and his family moved from Chicago to Dubuque where he founded Fountain of Youth in 2016 to help people break out of generational poverty. In the first week of January, 2020 the organization relocated to the building housing United Way of the Dubuque Area Tri-States. The move was significant to Jones who believed it would increase partnerships and programs, particularly those benefiting youth. In 2019 Fountain of Youth offered Partners in Change, a program in which 255 participants set short-and long-term personal goals. In the same year, Fountain of Youth made 209 referrals to other community agencies. (73)

Despite a federal study indicating that homelessness was declining in most states including Iowa, the Dubuque Rescue Mission officials in 2020 indicated a different conclusion. The shelter at 398 Main Street with 32 beds rarely had a single unused bed for a night. An additional 20 beds in the shelter's transition housing program were equally in demand. (74) In 2020 the latest census estimates reported that while accounting for 4% of Dubuque's population, an estimated 60% of African Americans living in Dubuque lived in poverty. (75)

In March 2021, the city manager requested the hiring of three employees to direct the creation of a proposed Office of Shared Prosperity. This would be responsible for the recently approved Equitable Poverty Reduction and Prevention Plan and coordinate with local nonprofits on collecting data on poverty in the community and developing poverty initiatives. In addition to hiring a director, data analyst and secretary, the city would shift the current community engagement coordinator position in the Human Rights Department to the new office. To reduce costs, the city staff would alter the existing neighborhood development specialist position to include the duties of directing the new department. The other two positions would need $102,355 to fill. (76)

By 2024 the number of tri-state residents who lived paycheck to paycheck--not considered low income but still struggling financially--continued to rise. The condition in which these people found themselves was described by the acronym ALICE (asset limited, income constrained, employed). These households made more than the federal poverty level but less than the cost of living for their area. In 2024 a single adult in the ALICE demographic needed $25,524 annually to meet the 2022 survival budget. One adult and one child needed $40,392. One adult with one child in daycare needed $44,796. In 20024 74% of single mothers with children fell below the ALICE threshold in Dubuque County. This compared to 45% of single fathers. Only 7% of married couples fell below the ALICE guidelines. In the City of Dubuque 20% of the households fell into the ALICE category with 13% below the poverty level. The greatest factor in causing households falling into the ALICE category was wages not keeping up with the cost of living. (77)

NOTE: There are many entries addressing this issue. See:

DUBUQUE COMMUNITY SCHOOL DISTRICT

---

Source:

1. "Poverty", Merriam-Webster Dictionary, Online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/poverty

2. "2017 Poverty Guidelines," U. S. Department of Health & Human Services, Online: https://aspe.hhs.gov/2017-poverty-guidelines#guidelines

3. "Prisoners of War," The Herald, April 20, 1887, p. 4

4. "Conquest of Poverty," The Telegraph-Herald, December 11, 1909, p. 4

5. "Union Supports Wage Law," Telegraph-Herald, September 4, 1973, p. 13

6. "The 'Good Old Days' Are Gone Forever," Telegraph Herald, November 15, 1993, p. 12

7. "Studies Tout Early-Childhood Education," Telegraph Herald, October 20, 2004, p. 21

8. Davis, J. W. "Sharing the Wealth--A Dream Coming True," Telegraph-Herald, April 10, 1966, p. 5

9. "Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program," Wikipedia, Online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supplemental_Nutrition_Assistance_Program

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Troan, John, "Health Benefits for the Needy," Telegraph Herald, August 11, 1965, p. 14

13. "'Upward Bound' Poor Funds for Iowa Colleges,'" Telegraph Herald, January 23, 1966, p. 10

14. "Increase Poverty Fund 500%," Telegraph Herald, January 21, 1966, p. 1

15. Schuster, Judy Burns,"Dubuque Poverty Plan Runs Into Hard Times," Telegraph Herald, November 4, 1965, p. 1A

16. Schuster, Judy Burns, "Dubuque Negroes Say Poverty, Rights Linked," Telegraph-Herald, November 19, 1965, p. 1A

17. Osweiler, Marilyn, "VISTA Looks for Young, Old Here," Telegraph-Herald, November 12, 1968, p. 15

18. Osweiler, Marilyn, "Private Agencies Lauded on Social Services Role," Telegraph-Herald, March 14, 1969, p. 9

19. "CAP Officials to Inspect Local Senior Citizens' Clubs," Telegraph-Herald, October 3, 1971, p. 17

20. Knee, Bill, "Food Aid Not Getting to Area Poor," Telegraph Herald, May 13, 1973, p. 23

21. Freund, Bob, "Tri-States Prepare Cheese Plans," Telegraph Herald, January 11, 1982, p. 4

22. "RU Making A Difference?" (advertisement) Telegraph Herald, July 17, 2014, p. 7

23. Fyten, David, "Help With Utilities Eyed For Poor," Telegraph Herald, March 11, 1975, p. 7

24. "Breakfast Plan Worth a Try," Telegraph Herald (editorial), March 29, 1991, p. 3

25. White, Norman, "Bread for the World Seeks More Help for Children," Telegraph Herald, July 25, 1992, p. 5

26. Gilson, Donna, "Housing-Needs Task Force Appointed," Telegraph Herald, September 12, 1990, p. 2

27. "City of Dubuque Opens Cooling Centers Due to Extreme Heat," Telegraph Herald, June 16, 2018, p. 5

28. Jerde, Lyn, "Habitat fror Humanity Helps Dubuque Family Buy Home," Telegraph Herald, April 26, 1994, p. 2

29. Eller, Donelle, "City Hires Women to Improve Neighborhoods," Telegraph Herald, December 3, 1994, p. 2

30. "Living in Poverty," (advertisement), Telegraph Herald, October 27, 2002, p. 103

31. Becker, Stacey, "Poverty Simulation Offers Perspective," Telegraph Herald, January 9, 2015, p. 3

32. Zmudka, Matt, "Teens Can Be Active, Rise to Dubuque's Challenge," Telegraph Herald, August 25, 2004, p. 13

33. "Feed the Need Auction, Luncheon Set for October 29th," Telegraph Herald, October 22, 2015, p. 8

34. "Youth Board Awards Grants," Telegraph Herald, July 17, 2011, p. 12

35. Kittle, M. D., "This is What You Call Poverty," Telegraph Herald, December 25, 2005, p. !A

36. "Feds Say More Weatherization Help on Way," Telegraph Herald, February 12, 2003, p. 14

37. Nevans-Pederson, Mary, "Bishop Shares Distaste for Bush's Economics," Telegraph Herald, March 15, 2005, p. 1A

38. Bassm Frank, Ben Feller and Nicole Ziegler Dizon, "'No Child' Loophole Leaves Out 2 Million Scores," Telegraph Herald, April 18, 2006, p. 9

39. "A Bridges Definition of Poverty," Telegraph Herald, July 24, 2011, p. 1A

40. Piper, Andy,"Program Combats 'Circle of Poverty," Telegraph Herald, September 15, 2010, p. 2A

41. Ibid.

42. Piper, Andy, "'Circles' Aims to Bridge Class Lines," Telegraph Herald, September 20, 2010, p. 1A

43. Piper, Andy, "'Allies' Offer Guidance Hope at Weekly Meetings," Telegraph Herald, July 24, 2011, p. 1A

44. Blanchard, Courtney and Andy Piper, "Study: Section 8's Impact Murky," Telegraph Herald, January 20, 2011, p. 6A

45. Hogstrom, Erik, "'It Doesn't Surprise Me At All," Telegraph Herald, September 24, 2011, p. 1A

46. Schmidt, Eileen Mozinski,"'People Have to Understand What Poverty Is,'" Telegraph Herald, September 20, 2012, p. 3A

47. Barton, Thomas J. and Craig Reber, "Poverty Rates Remain Stubborn," Telegraph Herald, December 16, 2015, p. 1A

48. Barton, Thomas J., "Diversity Spawns Push for Equity," Telegraph Herald, September 27, 2015, p. 1A

49. Barton and Reber, "Poverty..."

50. Ibid.

51. Barton, "Diversity..."

52. Ibid. p. 6

53. Ibid.

54. Barton, Thomas J., "Report: 1 in 5 Working Iowans' Wages Fall Short," Telegraph Herald, July 11, 2016, p. 1

55. Barton, Thomas J., "Dubuquers Vouch for Affordable Housing, Self-Sufficiency Programs," Telegraph Herald, February 19, 2016, p. 3

56. Montgomery, Jeff, "United Way Documents Working Poor Here," Telegraph Herald, June 29, 2018, p. 1A

57. Ibid.

58. Goldstein, Bennet, "Child Care Challenge," Telegraph Herald, October 10, 2018, p. 2a

59. Montgomery, Jeff, "Paycheck to Paycheck," Telegraph Herald, January 27, 2019, p. 6

60. Goldstein, Bennet, "Connections in the Classroom," Telegraph Herald, May 29, 2017, p. 1

61. Goldstein, Bennet,"CROP Walk on March Against Hunger," Telegraph Herald, October 8, 2018, p. 3

62. Montgomery, Jeff, "United Way Documents Working Poor Here," Telegraph Herald, June 29, 2018, p. 1A

63. Kruse, John, "City Council Ponders Perceptions," Telegraph Herald, March 12, 2019, p. 1

64. Fisher, Benjamin, "Dubuque Seeks Consultant for Anti-Poverty Plan," Telegraph Herald, July 22, 2019, p. 3A

65. Ibid.

66. Goldstein

67. Ibid.

68. Ibid.

69. Ibid.

70. Hinga, Allie, "Disparity of Diversity Fuels Calls for Redistricting," Telegraph Herald, February 10, 2019, p. 6

71. Hinga, Allie, "Resources Unite to Manage Aid Program," Telegraph Herald, August 18, 2019, p. 15A

72. Hinga, Allie, "Local Agency Relinquishes Head Start Contract," Telegraph Herald, August 8, 2019, p. 3A

73. Hogstrom, Erik, "New Location, Same Goals for Dubuque Organization," Telegraph Herald, January 10, 2020, p. 5A

74. Montgomery, Jeff, "Homelessness Persists in City," Telegraph Herald, January 17, 2020, p. 1A

75. Barton, Thomas J., "Dream Center's $276,000 Boost Coming True," Telegraph Herald, July 11, 2020, p. 1A

76. Kruse, John, "City Manager Requests Office of Shared Prosperity," Telegraph Herald, March 5, 2021, p. 2A

77. Bond, Maia, "'Not Those Stereotypes,'" Telegraph Herald, February 16, 2025, p. 1