Encyclopedia Dubuque

"Encyclopedia Dubuque is the online authority for all things Dubuque, written by the people who know the city best.”

Marshall Cohen—researcher and producer, CNN

Affiliated with the Local History Network of the State Historical Society of Iowa, and the Iowa Museum Association.

RAFTING: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

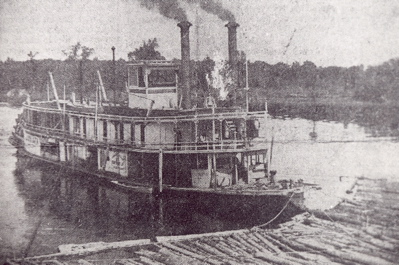

[[Image:raft-1.jpg|left|thumb|250px|]]Small steamboats including the "Firefly" and "Alva" were first used to guide the rafts in 1874. The success of the boats heralded a new age in the [[LUMBER INDUSTRY]] with the rafts growing larger by the year. Soon scores of boats with such names as the "J. K. Graves," "Neptune," and "Mountain Belle" were competing for business. Each raft contained between one million and three million feet of lumber. Crews of loggers on such rafts usually numbered eighteen men. Two men were hired as pilots for the boat because the raft was kept moving day and night. There were also two cooks and two firemen in the crew. | [[Image:raft-1.jpg|left|thumb|250px|]]Small steamboats including the "Firefly" and "Alva" were first used to guide the rafts in 1874. The success of the boats heralded a new age in the [[LUMBER INDUSTRY]] with the rafts growing larger by the year. Soon scores of boats with such names as the "J. K. Graves," "Neptune," and "Mountain Belle" were competing for business. Each raft contained between one million and three million feet of lumber. Crews of loggers on such rafts usually numbered eighteen men. Two men were hired as pilots for the boat because the raft was kept moving day and night. There were also two cooks and two firemen in the crew. | ||

[[Image:logs.jpg|right|thumb|250px|Photo courtesy: Bob Reding]]By 1881 there were few days in Dubuque when at least one raft was not stopped at a sawmill or pushed farther south to another mill. The W. J. Young mill in Clinton was the world's largest with the [[STANDARD LUMBER COMPANY]] being a close second. The last raft of logs passed beneath the [[DUBUQUE | [[Image:logs.jpg|right|thumb|250px|Photo courtesy: Bob Reding]]By 1881 there were few days in Dubuque when at least one raft was not stopped at a sawmill or pushed farther south to another mill. The W. J. Young mill in Clinton was the world's largest with the [[STANDARD LUMBER COMPANY]] being a close second. The last raft of logs passed beneath the [[DUNLEITH AND DUBUQUE BRIDGE]] on August 9, 1915, under the guidance of the "Ottumwa Belle." It was later found to be cheaper to have the timber sawed in the north and shipped south as planks. (Photo Courtesy: http://www.dubuquepostcards.com/) | ||

[[Category: Transportation]] | [[Category: Transportation]] | ||

[[Category: Postcards]] | [[Category: Postcards]] | ||

Revision as of 21:13, 23 March 2010

RAFTING. Process of floating large masses of logs downstream to sawmills. The first rafting on the MISSISSIPPI RIVER was done by LEAD miners who constructed platforms from logs to float their ore to St. Louis, Missouri. When the precious cargo was delivered, the logs themselves were sold before the miners again started north to their claims.

Loggers in the forests of Wisconsin often worked from early spring until ICE closed the rivers to the many mills along the river. When the weather became cold, they packed their clothing, left their families, and traveled to the primitive lumber camps of the north for a winter of cutting timber.

Lumber camps included men of European, French Canadian, and American ancestry. Large crews employed up to sixty men. Work was plentiful, as long as the timber supply in an area lasted. Supplies were hauled to the camps on sleds or occasionally wagons.

Heavy snow actually aided the tree-harvesting process. Once the snow was packed hard, teams of horses were used to pull the heavy logs out of the forest to a skidway. This was made of small logs used to guide the harvested trees down sharp embankments. Large logs were dragged on sleds. Once at the bottom of the hill, the logs were dragged again to the edge of the nearest stream.

With the coming of spring, the logs, marked by their owners, were floated downstream. Guiding the logs at this stage could often be done from shore with long poles. Where tributaries met larger streams, LOG RAFTS began to be formed. Here the lumbermen had to master the art of running across the logs, freeing those that had become snagged, and guiding the entire collection toward the mill. When logs became jammed the "key log" around which the jam had been created had to be found. Freeing the jam often required tools or dynamite.

While moving the rafts down the Mississippi, lumbermen lived in houseboats or in tents called "wanigans" which were mounted on rafts and floated with the lumber. Rafts allowed even non-buoyant types of wood to be carried by water. Such types of logs were lashed to logs that would float. This method became essential to the lumber industry after the passage of the Federal Rivers and Harbors Act of March 3, 1899. This act outlawed floating timber on streams in such a manner that would endanger or obstruct STEAMBOATS.

Hundreds of logs, rafted downstream at a cost of forty cents per thousand board feet of lumber, were enclosed in a boom fashioned from logs fastened with chains. As the loose logs inside the boom moved downstream they occasionally turned, making the movement by lumbermen over the top of the boom a dangerous venture. Progress downstream was slow. Before the use of steamboats, rafts drifted along at about three miles per hour.

Small steamboats including the "Firefly" and "Alva" were first used to guide the rafts in 1874. The success of the boats heralded a new age in the LUMBER INDUSTRY with the rafts growing larger by the year. Soon scores of boats with such names as the "J. K. Graves," "Neptune," and "Mountain Belle" were competing for business. Each raft contained between one million and three million feet of lumber. Crews of loggers on such rafts usually numbered eighteen men. Two men were hired as pilots for the boat because the raft was kept moving day and night. There were also two cooks and two firemen in the crew.

By 1881 there were few days in Dubuque when at least one raft was not stopped at a sawmill or pushed farther south to another mill. The W. J. Young mill in Clinton was the world's largest with the STANDARD LUMBER COMPANY being a close second. The last raft of logs passed beneath the DUNLEITH AND DUBUQUE BRIDGE on August 9, 1915, under the guidance of the "Ottumwa Belle." It was later found to be cheaper to have the timber sawed in the north and shipped south as planks. (Photo Courtesy: http://www.dubuquepostcards.com/)