Encyclopedia Dubuque

"Encyclopedia Dubuque is the online authority for all things Dubuque, written by the people who know the city best.”

Marshall Cohen—researcher and producer, CNN

Affiliated with the Local History Network of the State Historical Society of Iowa, and the Iowa Museum Association.

BARGE TRAFFIC: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

Repairs to the [[ZEBULON PIKE LOCK AND DAM]] came in 2018 when new miter gates were scheduled to be installed in late April or early May. The two upstream and two downstream gates collectively cost $3.1 million. The Dubuque lock and dam would also tainter gate chains replaced and lock relief wells installed later in the year. Lock No. 12 in Bellevue would have its miter gates replaced while Lock and Dam 10 at Guttenberg would have repairs to its damaged wall armor. A 2017 study by the University of Wisconsin suggested that the failure of any of the locks on the Upper Mississippi would result in an increase of nearly 50,000 ruckloads of freight on highways between Minnesota and Missouri. (20) | Repairs to the [[ZEBULON PIKE LOCK AND DAM]] came in 2018 when new miter gates were scheduled to be installed in late April or early May. The two upstream and two downstream gates collectively cost $3.1 million. The Dubuque lock and dam would also tainter gate chains replaced and lock relief wells installed later in the year. Lock No. 12 in Bellevue would have its miter gates replaced while Lock and Dam 10 at Guttenberg would have repairs to its damaged wall armor. A 2017 study by the University of Wisconsin suggested that the failure of any of the locks on the Upper Mississippi would result in an increase of nearly 50,000 ruckloads of freight on highways between Minnesota and Missouri. (20) | ||

In 2019 the Army Corps of Engineers announced plans for a potential $3.6 billion improvement to the current lock and dam system. Through the Navigation and Ecosystem Sustainability Program five new 1,200-foot locks on the Mississippi would be located south of Dubuque with two on the Illinois River. The goal of the program would be to solve costly delays of barges. The lock structures in Dubuque, Guttenberg, and Bellevue met the tow size needs of their day. Each is 600 feet long. The amount of freight, however, has increased dramatically resulting in twice as long for tows to pass through a lock. The NESP project had been suspended in 2011 due to a lack of federal funding. It's future would depend on its benefit-cost ratio. ( | In 2019 the Army Corps of Engineers announced plans for a potential $3.6 billion improvement to the current lock and dam system. Through the Navigation and Ecosystem Sustainability Program five new 1,200-foot locks on the Mississippi would be located south of Dubuque with two on the Illinois River. The idea of such large locks had first been proposed in 1993. (21) The goal of the program would be to solve costly delays of barges. The lock structures in Dubuque, Guttenberg, and Bellevue met the tow size needs of their day. Each is 600 feet long. The amount of freight, however, has increased dramatically resulting in twice as long for tows to pass through a lock. The NESP project had been suspended in 2011 due to a lack of federal funding. It's future would depend on its benefit-cost ratio. (22) | ||

For related information, refer to the "Search" feature of this encyclopedia. | For related information, refer to the "Search" feature of this encyclopedia. | ||

| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

20. Montgomery, Jeff, "Locks and Dams in Need of Major Upgrades Soon," ''Telegraph Herald'', February 14, 2018, p. 1A | 20. Montgomery, Jeff, "Locks and Dams in Need of Major Upgrades Soon," ''Telegraph Herald'', February 14, 2018, p. 1A | ||

21. Fisher, Benjamin, "Army Corps Studying 'Huge" Revamp of Locks," Telegraph Herald, February 27, 2019, p. 3 | 21. "More Barge Traffic? Six-Year Study Chugs On," ''Telegraph Herald'', November 9, 1993, p. 1A | ||

22. Fisher, Benjamin, "Army Corps Studying 'Huge" Revamp of Locks," Telegraph Herald, February 27, 2019, p. 3 | |||

Revision as of 19:10, 9 March 2023

BARGE TRAFFIC. Barge traffic has a long history on the MISSISSIPPI RIVER. Dating back the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, Congress guaranteed traffic on the Mississippi. Barges in Dubuque usually carry grain; coal; sand and gravel; fly ash; cement; motor fuels; and salt. A mistaken idea holds that a group of boats tied together is a barge. Each "boat" is actually a barge. "Line boats" push the linked barges up and down the river. "Switch boats" break up the tows to deliver barges to terminals for loading and unloading. (1)

Barge traffic normally opens around March 10th. (2) Barges are used for bulk items since the cost of hauling goods by barge is very low. In 1990 there were times of the year when Dubuque area farmers could save up to 50% getting their grain to market compared to other means of transportation. In 1989 INTERSTATE POWER COMPANY unloaded 940 barges of coal at its three plants. Wisconsin Power & Light Company burned an estimated 330 barge loads of coal annually. Representatives of both companies reported barge traffic costing significantly less than rail transportation saving consumers a great deal of money. (3) While costing less, a barge costs about $10,000 per day to operate. (4) In 2000 more than 300 million tons of freight were shipped on the Mississippi. (5) By 2020 this figure had risen to 763 million tons accounting for an estimated $253.2 billion in revenue and supporting about 750,000 jobs. (6) In 2015 it was estimated that it would take 58 large semi-tractor trailers or 13 railcars to transport the amount of product carried on a single barge. (7)

A typical barge measures 195 by 35 feet (59.4 m × 10.6 m), and can carry up to 1,500 tons of cargo. Extremely large objects are normally shipped in sections and assembled on site, but shipping an assembled unit reduced costs and avoided reliance on construction labor at the delivery site.

Self-propelled barges may be used when traveling downstream or upstream in placid waters. They are operated as an unpowered barge, with the assistance of a tugboat, when traveling upstream in faster waters.

In 1990 the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service was negotiating a land swap with ARTCO and NEWT MARINE SERVICE so that the two companies would own barge fleeting sites they had historically used on Pearl Island, south of the JULIEN DUBUQUE BRIDGE and Catfish Island. The sites were appraised at $230,000. The Wildlife Service asked the companies to acquire undeveloped industrial-style land of the same value, an estimated 500 acres, to add to the refuge. The fleet sites, appraised for their industrial value, included from between six to ten acres. The Catfish Island fleeting area alone could hold an estimated 100 barges. (8)

Temperatures play an important role in barge traffic. In 2015 above average temperatures in November and December increased the season barges could be used. The time as soon as ice formed could reach from eight to ten hours versus the normal one and one-half to two hours. Eventually ice closes the river to transportation completely.

In addition to warm temperatures, barge traffic depended on consistent water levels. In 2012 a drought reduced water levels in the Mississippi and Missouri rivers to such an amount that a bipartisan group of senators along both rivers urged President Obama to issue an emergency directive to permit additional water flows from the Missouri River reservoirs. This action, however, was rejected by the Army Corps of Engineers. (9) By November that year the Corps actually reduced the outflow from the Gavins Point Dam near Yankton, South Dakota to protect the upper Missouri River basin. (10) This act and continued falling river levels revealed two pinnacles of rock near the Mississippi River channel at St. Louis. These had to be removed with explosives before barge traffic could resume. In December, 2012 the Mississippi was below normal along a 180-mile stretch of river between St. Louis and Cairo, Illinois. The river channel, regularly at a width of 1,000 feet, was squeezed to only a few hundred feet. (11) Sonar was used to detect other rock formations missed when similar obstacles to transportation were removed to decades before. (12)

Environmental studies of the Midwest since the mid-1970s found that the average annual rainfall in the Upper Mississippi River Basin increased by about one inch per decade while frequency of two-day heavy rainfall events increased by 30%. In 2019 the Mississippi River experienced flooding for 85 days at Dubuque. While a drought was seen in 2020, both events indicated climate change. (13)

Climatologists around 2020 found that the average temperature of the planet was increasing approximately 0.4 degree per decade. While small, the increases caused more and more evaporation with the air holding more water. That allowed passing storms to tap into that water and create more rain events. This caused an increase in prolonged extreme weather events with increased evaporation causing drought conditions between each rainfall. Temperature increases were seem primarily during the winter and spring according to scientists at American Rivers, a non-profit organization which studied the Upper Mississippi Basin. Winters were shorter with storms which should have been snowfalls instead becoming rainfalls. (14)

Shippers along the Upper Mississippi River north of St. Louis could thank the system of LOCKS and dams for maintaining a manageable water depth. The engineers who designed the locks and dams designed the system to maintain a 9-foot channel under all flow conditions. The issue in 2013, however, was that the system was constructed in the 1930s with a life expectancy of fifty years. Even with rehabilitation in the 1970s and 1980s the structures are outdated.

In 2013 conservation groups took a lead in attacking the locks and dams for their cost. Olivia Dorothy, a regional conservation coordinator for the Izaak Walton League of America, claimed river barge traffic had decreased. According to Dorothy in a report entitled "Restoring America's Rivers," in 2012 shippers and barge companies paid only 10% toward the cost of the Inland Waterways Navigation System. This amounted to $80 million of the $800 million needed to keep the system in operation. Dorothy cited in comparison that 70% of the cost of maintaining roads and highways was paid through taxes on fuel and truck parts. (15)

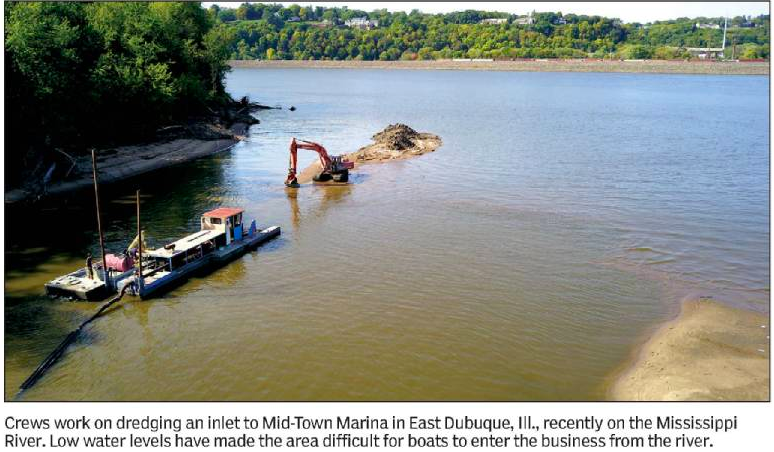

Dredging helped. Over the years the U. S Army Corps of Engineers spent millions of dollars on dredging with an average year costing about $2 million. In 2020 the Corps spent nearly $7 million and yet were "days or weeks away from a river closure" due to river levels continuing to drop. Some expenses fell directly on business owners. Owners of the DUBUQUE MARINA INC. reported in 2020 that the channel leading from the river to their business regularly filled in with silt and sand from flooding. The estimated cost in 2020 for dredging was expected to be $100,000. The water depth near the fuel dock made it inaccessible for several weekends to sell fuel. (16)

Barge owners recognize that low water conditions south of St. Louis still impact them. It has been calculated that for every loss of one-inch in depth in a river, a single barge must reduce its cargo capacity by 17 tons. This translated to barge operators needing to lighten loads to avoid sandbars and other low spots. More trips meant more costly transportation costs which were passed on to consumers. The U. S. Department of Agriculture estimated that the 2012 drought resulted in poultry costs rising from 3-4%, beef rising 4-5%, and dairy products rising 4.5%. (17)

Barges traffic is not without its risks to the public. Bargescarry a variety of products which could pose environmental threats. On June 9, 2008 fifteen fully loaded barges struck the JULIEN DUBUQUE BRIDGE. Fortunately ten of the barges were full of corn, four with soybeans, and one with iron ore. The bridge was closed to traffic until June 10th when Iowa Department of Transportation officials inspected the bridge and found no serious damage to the structure. (18)

Less fortunate was the relationship between barge traffic and the dispersal of ZEBRA MUSSELS. The mussels were first documented in Iowa in 1992 near Burlington. The following year, reports of the mussels came in from the entire length of the Mississippi River bordering Iowa. The mussels by 2011 were found in inland waterways in Wisconsin and the entire length of the Mississippi and the Illinois rivers. (19)

Repairs to the ZEBULON PIKE LOCK AND DAM came in 2018 when new miter gates were scheduled to be installed in late April or early May. The two upstream and two downstream gates collectively cost $3.1 million. The Dubuque lock and dam would also tainter gate chains replaced and lock relief wells installed later in the year. Lock No. 12 in Bellevue would have its miter gates replaced while Lock and Dam 10 at Guttenberg would have repairs to its damaged wall armor. A 2017 study by the University of Wisconsin suggested that the failure of any of the locks on the Upper Mississippi would result in an increase of nearly 50,000 ruckloads of freight on highways between Minnesota and Missouri. (20)

In 2019 the Army Corps of Engineers announced plans for a potential $3.6 billion improvement to the current lock and dam system. Through the Navigation and Ecosystem Sustainability Program five new 1,200-foot locks on the Mississippi would be located south of Dubuque with two on the Illinois River. The idea of such large locks had first been proposed in 1993. (21) The goal of the program would be to solve costly delays of barges. The lock structures in Dubuque, Guttenberg, and Bellevue met the tow size needs of their day. Each is 600 feet long. The amount of freight, however, has increased dramatically resulting in twice as long for tows to pass through a lock. The NESP project had been suspended in 2011 due to a lack of federal funding. It's future would depend on its benefit-cost ratio. (22)

For related information, refer to the "Search" feature of this encyclopedia.

---

Source:

1. Pritchard, Ken, "Barge Traffic a Boon to Tri-State Economy," Telegraph Herald, May 6, 1990, p. 1

2. Everly, John, "Barges Begin Spring Passage Through Locks," Telegraph Herald, March 15, 2002, p. 1A

3. Ibid., p. 3

4. Kruse, John, "River Reaction," Telegraph Herald, October 11, 2020, p. 5A

5. Everly

6. Kruse, p. 1A

7. Montgomery, Jeff, "Barge Traffic Still Humming Along," Telegraph Herald, December 7, 2015, p. 2A

8. Ibid.

9. Schmidt, Eileen Mozinsky, "Traffic Stoppage to Barge In?" Telegraph Herald, December 8, 2012, p. 1

10. Salter, Jim, "Corps Cuts Flow From Missouri River Reservoir," Telegraph Herald, November 24, 2012, p. 17

11. Salter, Jim, "Drought Jeopardizes Mississippi Barge Traffic," Telegraph Herald, November 30, 2012, p. 7

12. Salter, Jim, "Senator: Crews to Start Clearing Mississippi," Telegraph Herald, December 12, 2012, p. 17

13. Kruse, p, 5A

14. Ibid.

15. Reber, Craig D. "Corps Issue: Reinvest in Locks, Dams? Telegraph Herald, August 14, 2013, p. 1A

16. Kruse

17. Hogstrom, Erik, "On the Upper Mississippi, Barge Operators are Dam Grateful," Telegraph Herald, August 13 2012, p. 1A

18. Porter, Becka, "Fragile Waters," Telegraph Herald, June 22, 2010, p. 1A

19. Reber, Craig, "Fighting a Foreign Invasion," Telegraph Herald, September 15, 2011, p. 1A

20. Montgomery, Jeff, "Locks and Dams in Need of Major Upgrades Soon," Telegraph Herald, February 14, 2018, p. 1A

21. "More Barge Traffic? Six-Year Study Chugs On," Telegraph Herald, November 9, 1993, p. 1A

22. Fisher, Benjamin, "Army Corps Studying 'Huge" Revamp of Locks," Telegraph Herald, February 27, 2019, p. 3