Encyclopedia Dubuque

"Encyclopedia Dubuque is the online authority for all things Dubuque, written by the people who know the city best.”

Marshall Cohen—researcher and producer, CNN

Affiliated with the Local History Network of the State Historical Society of Iowa, and the Iowa Museum Association.

COMMERCIAL FISHING

COMMERCIAL FISHING. According to the Dubuque Herald on January 2, 1874, the commercial fishing was the best it had ever been on record. Using a seine three hundred yards long, Ernest Wiedner of Dubuque caught 50,000 pounds of fish at a spot near Lansing. The seine was drawn to the shore under the ice and then five days were needed to dip the fish out with hand-nets through holes in the ice. One sportsman was reported to have caught 250 pounds of walleye pike in one day through holes he cut in the ice along the shore. (1)

By 1911 the annual catch reached millions of pounds of fish with most shipped the New York City. One single haul of fish made on the Mississippi filled three railroad cars and resulted in $2,000 being paid to the fishermen who caught it. One twenty-mile section of the MISSISSIPPI RIVER resulted in payments to fishermen of an estimated $2,500 per mile. The entire river along Iowa's eastern border was thought to yield even better financial rewards. (2)

Fisherman in 1911 lobbied the Iowa legislature for changes which they announced could make fishing along the Mississippi worth an estimated $4,000 per mile. The first request was removing the prohibition on the trammel net which would improve fishing for carp and STURGEON. Cheap to buy and easily operated by one person, the claim was made that in fishing the CHANNEL no game fish would be caught. The fisherman also requested that the only restriction upon the kind of fish that could be harvested would correspond to the weight of the fish at "their maturity." Believing that the 'removal of one mature fish for this reasons means the preservation of scores of young fish" the change would mean that carp could be caught over 2.5 pounds, buffalo at 2.5 pounds, sand sturgeon at 1.0 pounds, rock sturgeon at 2.0 pounds, black bass at 1.0 pounds, striped bass at .5 pounds, crappies at .5 pounds, pike at 1.0 pounds, and pickerel at 1.5 pounds. For these changes, fisherman getting their license would agree to help conservation officers seine small fish caught in shallow ponds and move them to deeper water and/or dig channels for the young fish to swim to safety. (3)

The trammel net issue was not approved and commercial fisherman were still hoping to get the regulations changed in 1926. (4) Trammel nets finally received approval around 1960. (5)

Both sport and commercial fishing were benefits of work carried out by the Dubuque County National Youth Administration in 1937. During a one week period in July, an estimated 170,000 fish of many varieties were rescued from ponds and shallow sloughs by young men hired by the federal government. The fish had been swept into these places by high waters. As the water receded, the fish began dying. Among the valuable species rescued were blackk bass, catfish, pickerels, and crappies. (6)

A threat to sport and commercial fishing appeared in the Mississippi River by the late 1940s. LAMPREY EELS moving from the Great Lakes reached the river and began attaching themselves onto the side of a fish by way of its suction mouth. The eel then burrowed into the fish with disc-shaped teeth to feed on the fish's blood and body fluids. Few fish attacked by the eel survived. (7)

Commercial fishing in the winter began with stringing a net hundreds of feet long under the ice to complete two sides of an area into which fish would be driven. One the net was set, the fisherman moved several hundred feet above the net and began cutting holes in the ice. Fish were chased toward the net by plungers attached to long poles. Forcing the plungers into the holes cause noise to scare the fish. Once the fish were in the area of the net, the idea was to pull the around the other two sides of the area using strings and roles looped through holes in the ice. An area was generally fished using this method twice a season. (8)

In 1980, 754 fishermen reported commercial catches along the Iowa shoreline. This number, triple the number reported in the 1960s according to conservation officials, was due primarily to an increase in the number of part-time fishermen. Fish production in the states of Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, Missouri, and Wisconsin has remained fairly constant at an estimated eleven million pounds annually with a value of $1.2 million.

Statistics hide a gradual decline in the catches reported due to pollution, silting and over-fishing. The largest decline reported was in the number of catfish caught. The year 1966 marked the lowest number of this valuable fish being caught in three decades. Concern was so high, that conservation officials closed the season two weeks earlier than usual. (9) Catches in 1980 were 85 percent lower than the amount reported in 1965. Catfish have accounted for as much as one-third of a commercial fisherman's income leading to demands that size limits on catfish not be raised. Pools with the largest surface area annually reported the largest catches.

However, size did make a great difference. Iowa and Illinois both increased the minimum length requirements for catfish in the mid-1980s. Research found that another year of growth resulted in a fifteen inch catfish. Only about 20 to 30 percent of thirteen inch catfish were mature enough to spawn and lay eggs. In one year, the fish added two inches and the percentage of fish capable of fish capable of spawning rose to 80%. (10)

Whether eating fish from the river became a dispute between Minnesota and Wisconsin in 1989. Advisories in both states warmed fishermen to stay away from large, fatty, bottom-feeding fish like carp and catfish. In 1989 the Minnesota Department of Health warned sport fisherman not to eat more than one meal of month containing fish caught in the river. Pregnant women were never to eat river fish. The debate centered on polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, which were industrial byproducts shown to cause cancer on laboratory animals. Minnesota officials noted that their advisory was less restrictive than the one published in 1988 when it was advised not to eat any of several varieties of fish. (11)

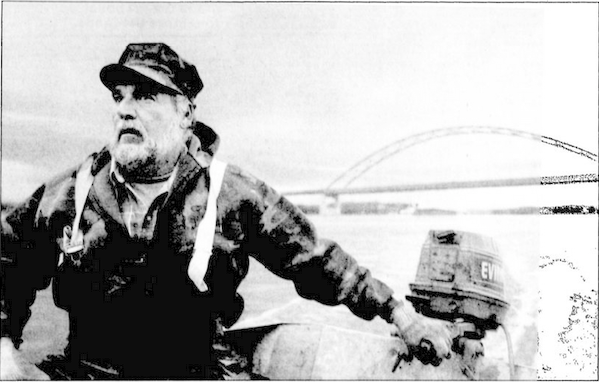

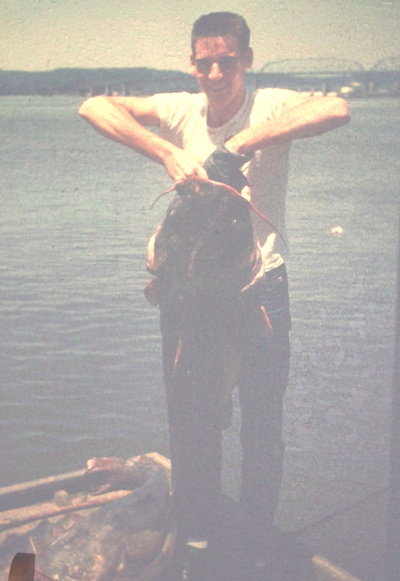

One of the successful commercial fishing families in Dubuque were the Duccinis--Fred; his son, Walter; his grandson, John; and for many years, Tom. Fishing a territory seven miles above and seven miles below Dubuque, the three generations run hoop nets, wooden box traps, trammel nets, gill nets and seines profitably for decades while also holding down other jobs at the packing company or The Adams Company. The self-described "cut-throat competition" of the industry led the family to often work at night. This avoided letting others know the best places to fish or the most efficient methods to use. Catches were brought in early in the morning; family members were involved in cleaning fish before they left for school. Tom Ducccini, a member of the HEMPSTEAD HIGH SCHOOL football team remembered coming to practice with a bandaged finger and needing to explain to a worried coach that he had been horned while cleaning a catfish that morning. (12)

John, Tom's father, began working in the business around the age of five. Trot lines carried one hundred hooks each. As they were brought out of the water, the fish were removed from the hooks and dumped into tubs. Lines had be wound carefully to avoid a mess. John ran trot lines for four years or until he was about eighteen. By then he had also had plenty of experience with "bank work" which included cleaning, boxing, and icing the fish for market. When he was in his teens, fishermen looked for trucks every three days to pick up their catch. They paid the drivers from 5-10 cents per pound to haul the fish to Chicago. Around 1990 as the price of fish dropped, families like John's packed fish in fifty gallon barrels, iced them, and drove to Savanna to sell their catch. Fish were sold to primarily to Chicago and New York, although the Duccinis once filled orders from Jerusalem. Fishermen in the Dubuque area suffered somewhat from their position on the river. Since the river was open further south, fisherman there made larger catches. Dubuque-area fishermen had to wait until the ice melted before returning to some of their better methods like hoop nets. (13)

John Duccini learned the fishing trade from his father. Signs in nature indicated when fish would probably be spawning. Lilacs in bloom meant it was time for carp. The snowy cottonwood predicted catfish spawn. When he was old enough to handle the business, his father gave John one-quarter of the profit for five years or until he had woven one hundred hoop nets. Working in the basement at night, John could manage to make about twenty-five nets per year. When the one hundred figure was reached, he shared in fifty percent of the profit. The most profitable fish to catch were catfish ($1.00-$1.50 per pound), sturgeon ($1.00 per pound), buffalo (35-40 cents per pound), an drum/sheephead (twenty-five cents per pound). Carp brought ten cents per pound before being smoked and sold in meat markets. Suckers were caught in the fall as they migrated down creeks to the river. These were pickled. (14)

In 2005 commercial fishing was described by one person as "fifty percent of does it so that you can make a little bit of money, but the other fifty percent is that we enjoy it. Prices (for fish) haven't changed much in thirty years. One minute you can make $200 and the next day yo can go out and not make a dime." The majority of this person's catch went to Schafer's Fisheries in Fulton, Illinois and they drove it there themselves. Commercial fishermen could only use certain areas of the Mississippi and its backwaters. Blamed for low prices were big waves that disturbed fish habitats and the advent of farm-raised catfish viewed as less likely to be contaminated. (15)

Conservation efforts have also played a role in complicating commercial fishing. Since overfishing caused the collapse of the traditional source of caviar, Caspian Sea sturgeon, the unfertilized eggs of the paddlefish became a popular alternative. The flesh of the fish was also considered a delicacy earning the nickname the "poor man's lobster." Fearing the pressure this would place on the rare paddlefish, Iowa banned its commercial fishing. (16)

Department of Natural Resources enforced commercial fishing regulations. In 2014 one commercial fisherman paid fines in excess of $3,000 for not having tags for his equipment and two counts of not having personal flotation devices. The agency also filed for condemnation of the boat, motor, trailer, and net. (17)

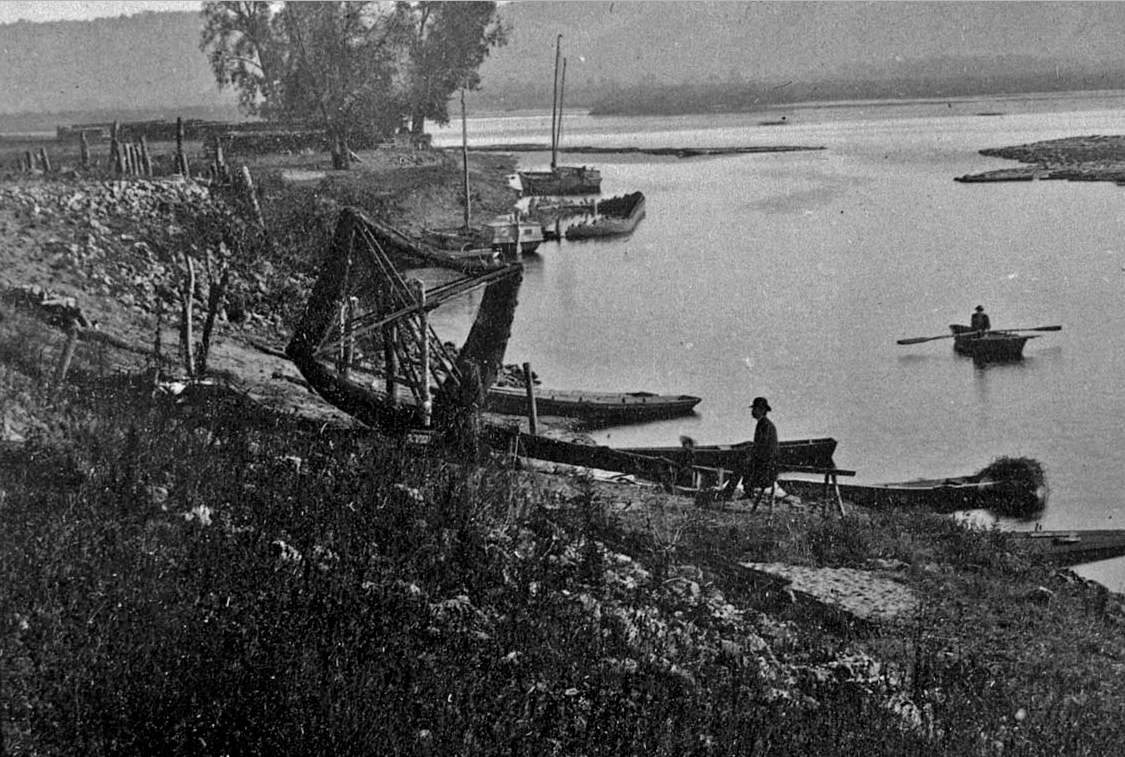

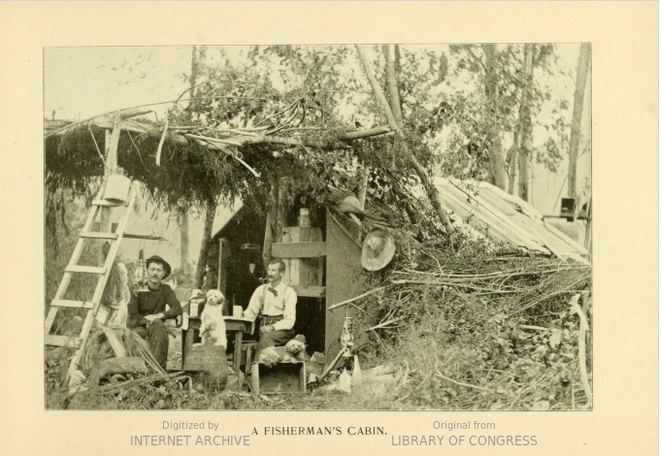

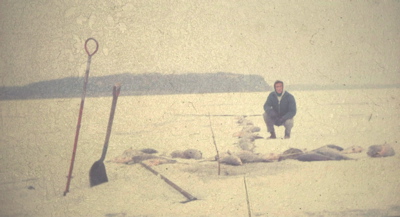

The following pictures were shared by John Duccini of his life on the river.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=10qia3AZ1mc Commercial fishing similar to Dubuque

---

Sources:

1. "The Fish Harvest," Dubuque Herald, January 3, 1874, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=uh8FjILnQOkC&dat=18740103&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

2. "Fishermen Would Change River Laws," Dubuque Telegraph-Herald, February 5, 1911, p. 4

3. Ibid.

4. "Commercial Fishing Around Dubuque is over for This Season," Telegraph Herald, November 22, 1926, p. 3

5. Patenaude, Joel, "Net Legacy," Telegraph Herald, June 7, 1996, p. 1A

6. "NYA Rescues 170,000 Fish In One Week," Telegraph-Herald, July 25, 1937, p. 22

7. "Killer Invades River," Telegraph-Herald, October 30, 1949, p. 18

8. "The River Ice," Telegraph-Herald, January 10, 1961, p. 13

9. "There'all Always be Catfish," Florence Shippley, Telegraph Herald, November 5, 1967. p. 9

10. Wilkinson, Joe, "Catfish Limits Translate into Better Catches," Telegraph Herald, August 24, 1997, p. 10

11. "Officials Disagree on Eating River Fish," Telegraph Herald, February 11, 1989, p. 21

12. John Duccini and Tom Duccini--interviews

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Fuerste, Madlelin, "Endangered Species," Telegraph Herald, June 12, 2005, p. 69

16. Nevans-Pederson, Mary, "Preserving the Paddlefish," Telegraph Herald, March 6, 2010, p. 1A

17. "Riverbank Project Threatens Rare Frog," Telegraph Herald, February 2, 2014, p. 35

Commercial Fishing. YouTube user:10qia3AZ1mc