Encyclopedia Dubuque

"Encyclopedia Dubuque is the online authority for all things Dubuque, written by the people who know the city best.”

Marshall Cohen—researcher and producer, CNN

Affiliated with the Local History Network of the State Historical Society of Iowa, and the Iowa Museum Association.

CIVIL DEFENSE

CIVIL DEFENSE. For the history of Civil Defense in the United States, see: http://www.civildefensemuseum.com/history.html

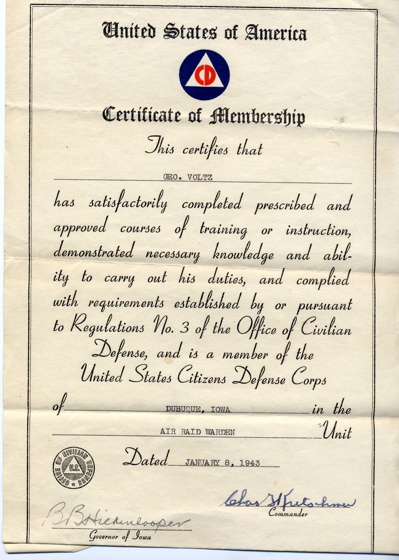

At the start of WORLD WAR II, it was decided that America needed some form of defense against the possibility of enemy attack. In May 1941, President Roosevelt created the Office of Civilian Defense (OCD). (1) The new Civilian Defense Board was to establish plans and programs for the protection of life and property against hazards of war and to work with state and local authorities to recruit and train civilian auxiliaries. The Board was also to mobilize a maximum civilian effort for carrying out the war including the enrollment of men. (2) Volunteers could chose from a variety of jobs, from being a member of the bomb squad to that most important job of all, the CD Air Raid Warden.

The U. S. Office of Civilian Defense in December, 1941, had directions published in local newspapers entitled "What To Do in an Air Raid" which basically said, "Keep Cool," "Stay Home," and "Put Out the Lights."In April 1942 nearly six hundred Dubuque residents enrolled in first aid classes. The classes were continued Monday and Tuesday evenings for seven weeks. (3) An OCD Activity List--a daily calendar of defense meetings began appearing in the newspaper in October, 1942. As an example, "The OCD Rescue Squad will meet at the Central Fire Station at 9th and Iowa, Thursday, at 7:30 p.m." (4)

Air Raid Wardens, wearing metal helmets and arms bands, would police the streets of during blackouts, making sure that every light was turned out, or at least hidden from view by a pair of heavy curtains. Sirens would sound to let people know it was once again safe to turn on their lights. Another field of activity was protection against accidents of student pilots involved in missing a target with a bomb or with crashes. Army bomb experts were ready to respond. OCD personnel were also involved in food production programs, salvage campaigns, and bond drives. (5)

Civilian Defense workers greatly aided local fire and police departments during blackouts and air raid alerts by filling the roles of officers who were now in the military. One area of increased activity was the protection against war gases. Aware of the risks in transporting these gases, specially trained officers located in most of the principal cities in the state were ready to take charge if sabotage or train wrecks occurred.

The responsibility for defense planning was under the control of the defense department until 1949. On March 3, 1949, President Harry Truman gave the responsibility to the National Security Resources Board (NSRB). This agency was charged with planning what the country should do in case of war or other great emergency. The NSRB established the Office of Civilian Mobilization (OCM). This meant that states and cities established plans for emergencies under OCM supervision. In 1950 OCM did not find Iowa among the states it considered had done good civil defense planning. (6)

In January 1951, at the height of the Cold War and the KOREAN CONFLICT, Congress passed the Civil Defense Act making possible cooperation between the federal government, states and cities to construct air raid shelters, train people, and establish warning systems. By August, 1951 President Truman and Millard Caldwell, chief of civil defense, asked Congress for $535 million to continue the program. In August, the House of Representatives, acted proposing only $65,255,000. In many ways, this mirrored the feeling of Dubuque's civil defense director in 1952. (7) In February, the Dubuque city Council authorized the attendance of the city's police and fire chiefs at a tuition free civil defense course at the State University of Iowa. (8)

March 29, 1951 was declared registration day by Iowa Governor William S. Beardsley. All registered or licensed practical nurses, active or inactive, were requested to register at the nearest county courthouse as part of civil defense. Administrators of hospitals with a large number of nurses could write to the courthouse and request the needed number of cards. (9)

In 1952 Colonel John B.Logan, chief of civil air defense for the Central Air Defense Force and C. E Fowler, deputy director of the Iowa Civil Defense Administration, spoke to a small audience at an adult education forum at WASHINGTON JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL. He described a "main street in the world" between the 33 degree and 66 degree north latitude lines around the world. Of the 360 degrees around the world, 165 lay within the Soviet Union. He went on to claim that what the air force had done to protect this country was very small. In addition he said there were too few radar stations. Fowler explained the civil defense on the national, state, county and city levels. Carleton Sias, assistant chief of Dubuque's GROUND OBSERVER CORPS, explained the duties and organization of the corps. An observer post was located on the roof of SUNNYCREST SANITORIUM. While unable to protect Dubuque, the observer would report any suspicious aircraft to Des Moines by telephone. Mrs. H. P. Lemper, county first aid chairman of the American Red Cross, explained the need for training citizens in first aid. Dr. A. G. Plankers, county medical director for civil defense, said his organization had inventoried hospital beds and cots, determined the capacity of buildings that could be used for emergency hospitals, and had a file of all medical personnel. Plans were underway to train medical personnel for specific injuries associated with bombings. Fire Chief Thomas Hickson, city director of civil defense, claimed the city was as ready as it ever would be. "Civil defense is something that people don't believe in. They just aren't scared enough. (10) President Truman called for 17.5 million more citizen volunteers, more equipment, and more medical supplies.

Preparations for Dubuque's participation in a nationwide 26-hour civil defense exercise on June 15-16, 1955 included the first use of the city's new $10,000 air raid sirens. The controls for the sirens were located at the telephone building. (11)

In 1957 Dubuque was not one of the cities "hit" by hypothetical atomic bombs during Operation Alert. This was fortunate because the city did not have a Civil Defense director or a working disaster plan. The situation had existed since 1956 when lack of participation threatened to shut down the Ground Observation Corps. The post should be manned around-the-clock since Dubuque was in a "Sky-Watch" area meaning it was susceptible to enemy air attack. According to the state civil defense plan, the city or county was "through appropriate ordinances to operate its civil defense system under the guidance of the state." Although this was brought to the attention of local government officials the response was they would not aid in financing any civil defense facilities before the state legislature approved such financing. (12)

In "Operation Alert", Iowa Civil Defense headquarters in Des Moines received a call that enemy plane were sighted over Alaska. State headquarters phoned other cities in the state. At 11:15 a.m. sirens began blasting away and remained going for ten minutes. When it was learned that Dubuque was not "hit," the city was to assume a support role. City manager Laverne Schiltz opened a letter at 1:00 p.m. which told him of "Dubuque's fate." (13)

On February 14, 1958 William Callaghan was appointed the Dubuque County director of civil defense. For two years before his appointment, there had been no director or active civil defense program. Callaghan found the major problem was general attitude. Reflecting the director in 1951, Callaghan found people were unconcerned. To counter this, he accepted speaking engagements to explain civil defense included floods, fires and earthquakes. On October 11th a Civil Defense Handbook for Emergencies was delivered by the Boy Scouts to every home in Dubuque. (14)

Callaghan led the organization to write up a 78-page manual establishing a five-year plan. It gave instructions for attack warning service, evacuation rescue service, communications, emergency welfare service, auxiliary police, and mobile hospitals. It also setup an evacuation map showing nine routes for removing people from the city. On May 6, 1958 the new group was also able to carryout a successful civil defense alert. Classes to train nurses aids at MERCY HOSPITAL began in August. (15)

In October 1960 Dubuque officials were considering a civil defense program independent of the county system. If implemented, it would be the first such program in Iowa. The city was currently contributing $1,520 to the county program. If the city decided on its own program, it would need to spend between $3,000-$4,000 on a similar program. Federal matching funds would be available. (16)

The 1961 Berlin Crisis and the Kennedy administration's reorganization of the national civil defense program led to an emphasis on a network of fallout shelter. While not designed to protect those inside against the blast itself, the shelters were meant to save lives during the following weeks with supplies of food and water. Soon after the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, the U. S. Office of Civil Defense (later renamed Defense Civil Preparedness Agency) began creating a network of shelters nationwide to protect people from radioactive fallout for a period of two weeks. Booklets were prepared showing individuals how to build shelters and what to do in case of nuclear attacks. In 1976 Robert P. GOOCH, the director of Dubuque County civil defense, remarked," There's no way of telling how many fallout shelters are still in Dubuque homes. A lot of people with means didn't want to be part of a public effort and picked up plans. I'm sure that a lot of these shelters are family rooms now." (17)

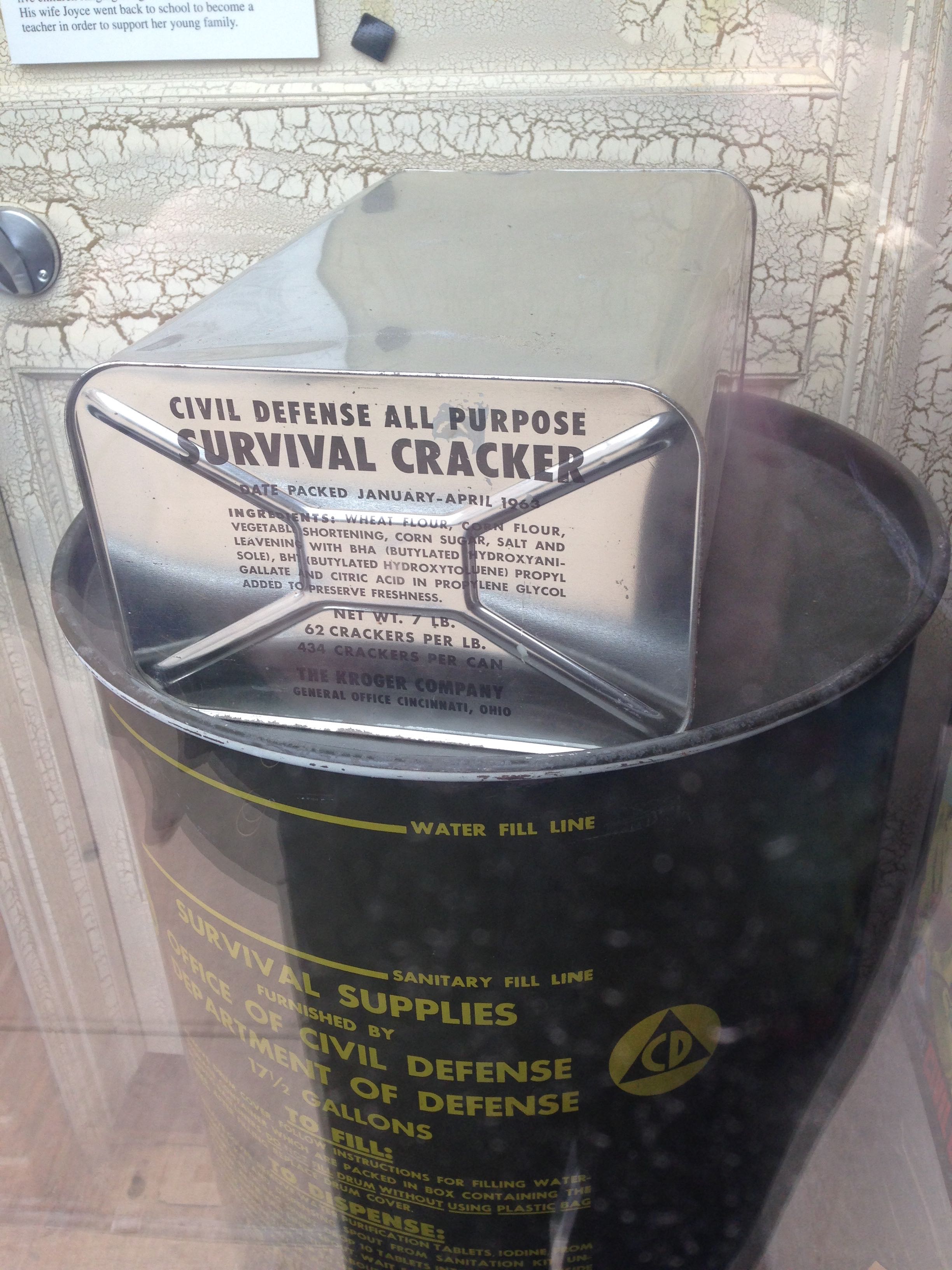

The first yellow-and-black civil defense fallout shelter signs were posted on December 5, 1962 on the doorways to official fallout shelters in Dubuque buildings. (18) The largest natural fallout shelter was located near Clayton, Iowa. Established in a silica mine, the shelter was stocked in 1963 with 500,000 pounds of supplies including 220,104 pounds of survival crackers, 154,000 gallons of water, and 881 medical kits. It was estimated that 44,016 people could be supplied for two weeks. The figure could be raised to 78,000 with a system of forced air ventilation. (19)

The Dubuque Civil Defense Office in February, 1963 was anxiously looking for volunteers. An estimated 50 tons of food and equipment for 49 public shelter spaces was expected to arrive by commercial carriers under contract to the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers. (20)

In 1966, the Iowa law allowing the civil defense department to plan for natural disasters as well as nuclear attack was passed. (21)

The Iowa Civil Defense Division began a program in April, 1967 to find an additional 2 million fallout shelter spaces in the state. While a group of fourteen women were interviewing homeowners in rural areas, citizens of Dubuque and large cities received questionnaires. Once these were returned an evaluated, the homeowner would receive a "protection factor" indicating how well the residents would be shielded after a nuclear attack. The reply would also indicated what part of the home would be the best for shelter. (22)

In 1968 Dubuque was one of the few towns in the Tri-State area to have a Civil Defense warning siren and a carefully planned warning system. The Dubuque weather bureau was responsible for contacting adjoining counties with disaster warnings and alerts through the Dubuque County sheriff's office. There was a county-wide system of spotters living within a five-mile radius of a community in Dubuque County with the responsibility of notifying their town's Civil Defense officials if they saw funnel clouds or other signs of bad weather. George Orr, the Iowa Civil Defense Director, stated that city officials were reluctant to spend the money on tornado warning systems. This was despite the fact that a city installing an system would receive half of the cost reimbursed by the federal government. (23)

In 1969 the fallout program championed in 1961 offered little. A study indicated that: (24)

* 40% of the shelters were not marked

* only 50% were stocked with food and water

* many shelters had no trained manager

* less than 2% of homeowners with suitable homes

for shelters had written for plans to upgrade

* rural areas typically had one shelter space for

every four people

Dubuque County-Municipal Defense officials in April, 1970 adopted a nuclear fallout shelter plan for Dubuque County residents. A survey by the Army Corps of Engineers found 81,495 shelter spaces in five sections of the city and county. An estimated 100,000 people were planned for including residents and 6,000 students. The boundaries of the areas and directions for reaching the shelters was to be printed in a special 16-page supplement to the Telegraph Herald. (25)

Civil Defense in 1971 announced its award of $27 million to Westinghouse Electric Corp. to begin work on the new Decision Information Distribution System (DIDS). In the plan, special radio receivers would be placed in law enforcement agencies, firehouses, and state and local agencies that would notify the public of an emergency. In the event of a disaster, the warning control officer at the North American Air Defense Command (NORAD) would activate 11 low-frequency radio transmitters around the nation. Within thirty seconds, the transmitters would send a warning to the 30,000 radio receivers which would activate air raid sirens. (26)

Dubuque residents found in July, 1971 that the city had no all-clear civil defense signal. Officials at both the local and state levels believed such a signal would create more confusion. Residents could turn to their local radio stations if they realized it took time to become aware of the weather and time to get on the air. As WDBQ program director Paul HEMMER commented, "WDBQ signed on basically because I woke up and decided there was need for some kind of information." (27)

In 1973 a group of forty-five volunteers training, under the supervision of the DUBUQUE POLICE DEPARTMENT four hours each month, comprised the Dubuque Civil Defense Auxiliary Police. They were supplements to the police in emergencies such as traffic or crowd control. Other duties included patrolling the city in their own cars and reporting any suspicious activity. They paid for their own uniforms as well as the gasoline and oil used on patrol. They were not armed and did not play a role in arresting or questioning suspects. (28)

In May, 1974 the Civil Defense director christened Dubuque's first river rescue boat. Powered by a 160-horsepower outboard, the boat was capable of speeds up to 55 mph. While technically on loan from the federal government, full ownership of the vessel could pass to the city at the end of a five-year loan period. It was to be used for emergencies and not routine patrols. (29)

In 1976 about half of the tri-state's 438 public fallout shelters with 138 in Dubuque County remained stocked with supplies. Food remained edible as long as the tins were kept dry and sealed. Some medical supplies including penicillin and nose and eye drops were removed because they had lost their potency. Bottles of phenobarbital, a depressant, were removed from all fallout shelters during the 'drug craze' of the 1960s. Public fallout shelters were inspected every two years, but a new plan was being promoted. Residents of high-risk cities were being evacuated to rural areas and small towns. People who had to use the shelters were asked to bring their own food. Grocery stores might also be taken over for supplies. (30)

In 1976 the largest shelter in Dubuque was the FARLEY AND LOETSCHER MANUFACTURING COMPANY building at 198 E. 7th St. It was estimated that 6,380 people could use it for shelter. The second and third largest potential shelters was MERCY MEDICAL CENTER and the DUBUQUE PACKING COMPANY. (31)

---

Source:

1. "FDR Reorganizes Civil Defense," Telegraph-Herald, April 16, 1942, p. 13

2. Ibid.

3. "Civilian Defense Classes Draw 600," Telegraph-Herald, April 19, 1942, p. 13

4. "On the OCD Activity List," Telegraph-Herald, October 8, 1942, p. 4

5. "OCD Subs for City Employees," Telegraph-Herald, December 19, 1943, p. 11

6. "Civil Defense Not Organized," Telegraph Herald, July 19, 1950, p. 12

7. "Civil Defense Periled by Cut," Telegraph Herald, August 23, 1951, p. 4

8. "Police, Fire Chiefs to Attend Course in Civil Defense," Telegraph Herald, February 6, 1951, p. 3

9. "Nurse Can Mail Registration," Telegraph Herald, March 18, 1951, p. 5

10. "Civil Defense Lag Lamented," Telegraph Herald, March 6, 1952, p. 24

11. "Raid Sirens to Play Big Part in Test," Telegraph Herald, June 8, 1955, p. 2

12. Simplot, John. "Dubuque Civil Defense Close to 'Death' From Disinterest," Telegraph Hesrald, July 15, 1958, p. 10

13. "Alert 'Bombs' Miss Dubuque," Telegraph Herald, September 12, 1957, p. 1

14. "Civil Defense Goal is 'Readiness,'" Telegraph Herald, August 24, 1958, p. 9

15. Ibid.

16. "Civil Defense Program for Dubuque Considered," Telegraph Herald, October 9, 1960, p. 9

17. Fyten, David. "Many Fallout Shelters in Tri-States Still Ready," Telegraph Herald, February 22, 1976, p 10

18. "Fallout Shelter Signs," Telegraph Herald, December 6, 1962, p. 16

19. "Mine Fallout Shelter Biggest in Tri-States," Telegraph Herald, June 9, 1963, p. 37

20. "Civil Defense Needs Helpers," Telegraph Herald, February 13, 1963, p. 8

21. "Iowans Better Prepared for Natural Disaster," Telegraph Herald, May 31, 1972, p. 6

22. "Iowa Survey of Homes Begun to Find More Fallout Shelters," Telegraph Herald, April 3, 1967, p. 11

23. Hansen, Christine, "Disaster Warning Systems Lacking," Telegraph Herald, June 6, 1968, p. 16

24. "Civil Defense 'Falls Down' On Fallouts," Telegraph Herald, May 7 1969, p. 10

25. Richins, Dave. "Civil Defense Plan Completed," Telegraph Herald, April 29, 1970, p. 4

26. "New Attack Alert More Reliable," Telegraph Herald, July 18, 1971, p. 6

27. Tighe, Mike. "In the Aftermath of Early Morning Storm..." Telegraph Herald, July 11, 1971, p. 10

28. "Action Line," Telegraph Herald, March 21, 1973, p. 22

29. "Trial Run," Telegraph Herald, May 3, 1974, p. 9

30. Fyten

31. Ibid.