Encyclopedia Dubuque

"Encyclopedia Dubuque is the online authority for all things Dubuque, written by the people who know the city best.”

Marshall Cohen—researcher and producer, CNN

Affiliated with the Local History Network of the State Historical Society of Iowa, and the Iowa Museum Association.

AIR POLLUTION

AIR POLLUTION. Federal involvement in confronting air pollution and its results began in 1955. In that year, Congress gave the Public Health Service authority to supply money and leadership to individual states, universities, and research groups. In the following three years, $8.5 million was spent in 32 research projects dealing with pollutants and their behaviors. There were 73 full-time air pollution control centers across the nation with most located in industrial states. There were also sixty part-time control agencies. The burden of the fight against air pollution, however, rested on the individual community. (1) In 1954 Mayor Clarence P. WELU issued a proclamation designating October 19-25th, 1958 as Cleaner Air Week. Welu stated that air pollution "of all forms is a menace to the health, cimfort, and economy of our fellow citizens. (2) In 1959 Mayor Charles KINTZINGER urged all citizens to follow efforts of committees to "save our city from property damage and loss due to air pollution." (3)

City officials joined the National Air Sampling Network on January 1, 1963. As a partner, the city sent air pollution data to federal laboratories. (4) Beginning in December, 1963 city employees began collecting data as a basis for a Dubuque ordinance designed to control air pollution. Sampling stations to detect solid particles of pollution were set up around the city. In May, 1966 a gas detection station was established at Ninth and Iowa STREETS. Equipment was later installed to trap particles that did not drop into sample jars. This new equipment drew air through filters trapping the particles. (5) Results of the tests, which provided no surprises, showed the amount of sulphur dioxide, a product of burning coal, was high in the downtown area. (6)

In 1963 Dr. Albert J. Entringer, the Dubuque director of health, stated his belief that air pollution could be a factor in some chronic disease cases here, but the situation was not considered acute. The Dubuque air condition had been brought before the city council in early December, 1962. A petition signed by 96 residents claimed relief from soot they believed damaged their homes. Gilbert D. CHAVENELLE, the city manager explained that air samples were being collected. In addition a study was being made as to how other cities were handling the matter. The closest law Dubuque had to pollution abatement dealt with leaf burning. The law stated that leaves could only be burned in a proper incinerator and at least fifty feet from the nearest frame building. A twice weekly trash and garbage pickup had nearly eliminated leaf burning. The cost of an effective control agency was expected to range from $6,000 to $36,000. (7)

Air pollution in Iowa in 1963 was a problem for individual communities according to Dr. Charles Campbell of the Iowa Division of Health. Federal activities on air pollution was limited to research, technical assistance and training. (8)

Dubuque industries by 1963 had taken steps to reduce their contribution to the problem. INTERSTATE POWER COMPANY had spent more than $100,000 over three years to reduce undesirable exhausts. DUBUQUE PACKING COMPANY had installed equipment that burned the coal so that there was no soot or ash. The conversion from coal to gas or oil furnaces also helped. CARADCO utilized a cyclone separator to remove sawdust and fine wood particles from the air. Automobiles were blamed for producing 3.2 metric tons of carbon monoxide, 400-800 pounds of organic vapors, and between 100-300 pounds of nitrous oxides. New cars were equipped with devices to reduce these numbers. (9)

The cooperation of the city in the national research project and efforts of local industry did not affect the assessment of the city's air pollution. On November 10, 1966 news was released by the U. S. Health Department that Dubuque was one of the 26 worst cities in the nation in air pollution. Art Roth, Dubuque city chemist, was quick to point out that the sampling station used for the data was located in the center of the industrial area--a site recognized as the worst in the city. Other cities including Des Moines and Cedar Rapids were reported to have more than 100 micrograms of dirt per cubic meter of air. Dubuque had approximately 150 micrograms. (10)

The Dubuque ordinance was still in development in January, 1968. Analysis of the collected data indicated that the Fourth Street Extension station area had 76.3 tons of foreign matter per square mile; Flat Iron Park had 61.2 tons; and Maple Wood Court, a residential area, had a reading of 4.6 tons. The readings were found in the spring and fall.

Weather played an important role in pollution measurements. Spring and fall were the seasons of highest pollution because of the differential between warm and cold air was higher. Layers of either warm or cold air trapped pollution. Stationary high pressure centered over the Iowa-Missouri border held noxious gases over the southeastern two-thirds of Iowa in 1975. The stagnant air allowed sunlight to react with auto and industrial emissions to create ozone, a gas that troubled people with heart or respiratory ailments. The potential of several Dubuque industries having to shut down temporarily was raised as Iowa moved toward its first air pollution alert in its history. (11) If pollutants become airborne, weather conditions play an important role in how much and how concentrated the pollutants would be. (12) This was shown in March, 1968 when Dubuque's air pollution rose due to the scrubbing action of rain and snow which trapped more pollutants otherwise suspended in the air. (13)

In May, 1971 Arthur Roth explained the City Health Department's air pollution control plans to the city council and suggested an ordinance would be presented in 1972. Final plans awaited finding out what state and federal government standards would be proposed. The ordinance he envisioned would permit city inspectors to inspect industrial plant plans before construction to ensure enough pollution control equipment and permit inspection of these control devices once in use. (14)

He also found the city responsible for much of the air pollution. Air quality had improved when the city discontinued open burning on CITY ISLAND. Roth wanted the city's three-year-old open burning ban extended year-round. Collection of air samples three times since 1964 led to Dubuque earning a "dirty city tag." (15)

In 1973 the Dubuque Interstate Air Quality Control region was established. This included Dubuque, Clayton and Jackson counties in Iowa; Grant County, Wisconsin; and Jo Daviess County, Illinois. Of the 216,971 tons of pollutants collected, a total of 82,467 were emitted by Wisconsin Power & Light Company's Nelson Dewey Station and Dairyland Power Cooperative Stoneman Station of Cassville and Interstate Power Company of Dubuque. This pollution was expected to decline significantly by 1975 as a result of control equipment installed due to provisions of the federal 1970 Clean Air Act. Of five categories of air pollutants only particulates were present in concentrations exceeding the federal standard established to protect the public's health. (16)

Most of the credit in 1974 for Dubuque's air being the cleanest at any time it had been measured was given to Interstate Power's new pollution-control equipment. The electrostatic precipitator removed more than 99% of the fly ash from the company's largest boiler. (17)

In 1978 Dubuque's air made the national smog list along with Cedar Rapids, Des Moines, Davenport, Council Bluffs, Fort Dodge, Mason City, Keokuk and Sioux City. These cities exceeded limits for sulfar dioxide, an industrial contaminant. Consideration of placing a model of Dubuque in a wind tunnel to see where the pollutant came from, however, were stopped due to the price tag of $50,000. (18)

In 1980 Iowa approved a framework for state air pollution standards changing definitions in the Iowa law to comply with the Federal Clean Air Act. Approved on a 92-0 vote, the bill avoided an attempt by federal officials to write laws for Iowa through the Department of Environmental Quality. In 1979 the federal government disapproved a draft from Iowa because it did not deal with "fugitive dust," windblown dust from fields and rural roads. (19)

The local government in Dubuque and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) were the targets of the National Clean Air Coalition in 1987. Dubuque was one of at least sixty areas of the country not meeting ozone pollution levels between 1983 and 1985 set by the federal Clean Air Act. Dubuque officials claimed they had received no complaints from the EPA. Spokespersons for the coalition claimed the EPA was slow to consider new programs and give local governments help in controlling pollution. (20) The charge was dismissed by an environmental specialist with the Iowa Department of Water, Waste and Air Management. Between 1982 and 1985 carbon monoxide levels in Dubuque had exceeded standards seven times with three occurring in 1983. The level had to exceed the standard at least twice in a year to qualify as a violation of EPA regulations. When Dubuque had exceeded the standard, it was "just right above the standard. In 1980 Dubuque had been placed on a "non-attainment" lost for exceeding carbon monoxide standards eleven times. After consistently meeting the standards, it had been removed. (21)

Air pollution in the home, according to EPA studies cited in 2008, could be more than 100 times higher than outdoor levels. Sources included central heating, household cleaning and maintenance products, animal dander, mold, tobacco smoke styrene found in adhesives and insulation, and formaldehyde from fabrics. Remedies included improved ventilation, smoking outside, and the use of test kits. RADON could be lessened by sealing cracks in foundations or with the installation of exhaust systems. (22)

In 2011 ALLIANT ENERGY CORPORATION switched from coal to natural gas at its Dubuque station which was set to close in 2017. The city spent $70 million to retrofit its wastewater treatment plant and ceased incinerating byproducts and instead captured methane from its anaerobic digestion process to generate electricity. (23)

The Iowa Department of Natural Resources Air Quality Bureau in 2014 awarded the City of Dubuque an $80,000 grant to help retrofit two dump trucks and two utility trucks with high-tech filters and mufflers. Such equipment was capable of reducing particulate matter from the older vehicles by up to 85%. (24)

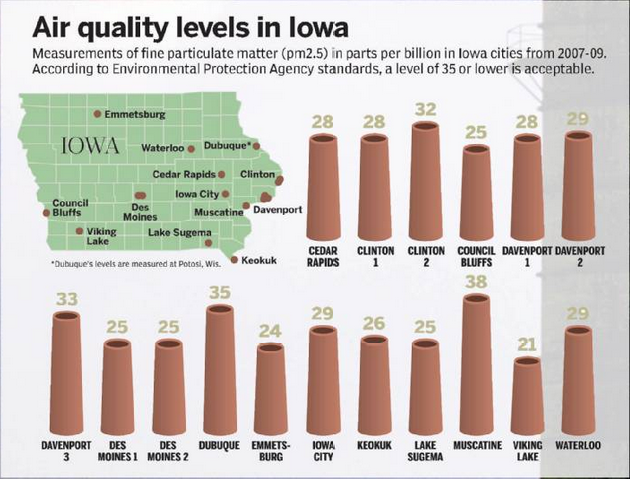

In 2016 the City of Dubuque and the University of Iowa developed a collaboration to improve air quality in Dubuque. The partnership developed after the university received a $91,000 grant from the EPA to help Dubuque raise awareness about the causes and health effects of air pollution. According to the grant, the university would purchase monitors and train businesses, nonprofits, colleges and high school on how to use them to track air quality. At the time, the closest air-monitoring station to Dubuque was located in Potosi, Wisconsin. Data gathered there was reported to the EPA. Between 2005 and 2009, Dubuque was close to exceeding federal standards. To avoid federal regulation, the city entered into an EPA program allowing voluntary measures to improve air quality. Since 2010, air-pollution in Dubuque dropped. (25)

---

Source:

1. Danzig, Fred, (United Press Staff), "What Comes Out the Chimney?" Telegraph-Herald, May 6, 1958, p. 2

2. "Columbus Day, Cleaner Air Week Proclaimed," Telegraph-Herald, September 21, 1958, p. 10

3. "Oct. 25-31 Proclaimed As Cleaner Air Week," Telegraph-Herald, September 14, 1959, p. 3

4. "Pick 8 Sites for Air Study," Telegraph-Herald, November 12, 1963, p. 4

5. Hooten, Leon, "Air Pollution Ordinance Shaping Up," Telegraph-Herald, January 5, 1968, p. 11

6. "Pollution Test No Surprise," Telegraph-Herald, November 17, 1964, p. 6

7. Thompson, Dave,"Trouble Brewing in Dubuque's Air," Telegraph-Herald, March 3, 1963, p. 11

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. "City's Air Pollution Rating Held Unfair," Telegraph-Herald, November 10, 1966, p. 1

11. "Industrial Shutdown Possible in Basin Air Quality Worsens," Telegraph-Herald, July 3, 1975, p. 8

12. Hooten

13. "Air Pollution," Telegraph-Herald, March 16, 1965, p. 3

14. Bulkley, John, "Anti-Air Pollution Ordinance Seen Next Year," Telegraph Herald, May 30, 1971, p. 5

15. Ibid.

16. Knee, Bill, "Air Pollution Picture: Bad, But Getting Better," Telegraph-Herald, May 13, 1973, p. 1

17. Knee, Bill, "City Air Cleaner Than Ever," Telegraph-Herald, October 1, 1974, p. 1

18. Freund, Bob, "City Air 'Dirty;' Tunnel Test Dropped," Telegraph Herald, March 7, 1978, p. 1

19. "House Approves State Air Pollution Standards," Telegraph Herald, March 11, 1980, p. 4

20. " 'Health Endangerment Areas' List Includes Dubuque," Telegraph Herald, April 26, 1987, p. 2

21. Blocker, Sue, "Dubuque Air Quality Not So Bad," Telegraph Herald, April 27, 1987. p. 8

22. Carey, James and Morris, "Determining If Your Home is Making You Sick," Telegraph Herald, January 20, 2008, p. 71

23. Barton, Thomas J. "City, U of I Pair Up to Pursue Clean Air," Telegraph Herald, Dec. 11, 2015, p. 1

24. "80,000 Grant to Help City Retrofit Vehicles to Reduce Air Pollution," Telegraph Herald, December 26, 2014, p. 3

25. Barton, p. 2