Encyclopedia Dubuque

"Encyclopedia Dubuque is the online authority for all things Dubuque, written by the people who know the city best.”

Marshall Cohen—researcher and producer, CNN

Affiliated with the Local History Network of the State Historical Society of Iowa, and the Iowa Museum Association.

CIVIL DEFENSE: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

In Operation Alert, Iowa Civil Defense headquarters in Des Moines received a call that enemy plane were sighted over Alaska. State headquarters phoned other cities in the state. At 11:15 a.m. sirens began blasting away and remained going for ten minutes. When it was learned that Dubuque was not "hit," the city was to assume a support role. City manager Laverne Schiltz opened a letter at 1:00 p.m. which told him of "Dubuque's fate." (1) | In Operation Alert, Iowa Civil Defense headquarters in Des Moines received a call that enemy plane were sighted over Alaska. State headquarters phoned other cities in the state. At 11:15 a.m. sirens began blasting away and remained going for ten minutes. When it was learned that Dubuque was not "hit," the city was to assume a support role. City manager Laverne Schiltz opened a letter at 1:00 p.m. which told him of "Dubuque's fate." (1) | ||

The 1961 Berlin Crisis and the Kennedy administration's reorganization of the national civil defense program led to an emphasis on a network of fallout shelter. While not designed to protect those inside against the blast itself, the shelters were meant to save lives during the following weeks with supplies of food and water. | |||

In 1968 Dubuque was one of the few towns in the Tri-State area to have a Civil Defense warning siren and a carefully planned warning system. The Dubuque weather bureau was responsible for contacting adjoining counties with disaster warnings and alerts through the Dubuque County sheriff's office. There was a county-wide system of spotters living within a five-mile radius of a community in Dubuque County with the responsibility of notifying their town's Civil Defense officials if they saw funnel clouds or other signs of bad weather. George Orr, the Iowa Civil Defense Director, stated that city officials were reluctant to spend the money on tornado warning systems. This was despite the fact that a city installing an system would receive half of the cost reimbursed by the federal government. (2) | The first yellow-and-black civil defense fallout shelter signs were posted on December 5, 1962 on the doorways to official fallout shelters in Dubuque buildings. (2) The largest natural fallout shelter was located near Clayton, Iowa. Established in a silica mine, the shelter was stocked in 1963 with 500,000 pounds of supplies including 220,104 pounds of survival crackers, 154,000 gallons of water, and 881 medical kits. It was estimated that 44,016 people could be supplied for two weeks. The figure could be raised to 78,000 with a system of forced air ventilation. (3) | ||

In 1966, the Iowa law allowing the civil defense department to plan for natural disasters as well s nuclear attack was passed. (4) | |||

The Iowa Civil Defense Division began a program in April, 1967 to find an additional 2 million fallout shelter spaces in the state. While a group of fourteen women were interviewing homeowners in rural areas, citizens of Dubuque and large cities received questionnaires. Once these were returned an evaluated, the homeowner would receive a "protection factor" indicating how well the residents would be shielded after a nuclear attack. The reply would also indicated what part of the home would be the best for shelter. (5) | |||

In 1968 Dubuque was one of the few towns in the Tri-State area to have a Civil Defense warning siren and a carefully planned warning system. The Dubuque weather bureau was responsible for contacting adjoining counties with disaster warnings and alerts through the Dubuque County sheriff's office. There was a county-wide system of spotters living within a five-mile radius of a community in Dubuque County with the responsibility of notifying their town's Civil Defense officials if they saw funnel clouds or other signs of bad weather. George Orr, the Iowa Civil Defense Director, stated that city officials were reluctant to spend the money on tornado warning systems. This was despite the fact that a city installing an system would receive half of the cost reimbursed by the federal government. (6) | |||

In 1969 the fallout program championed in 1961 offered little. A study indicated that: (7) | |||

* 40% of the shelters were not marked | |||

* only 50% were stocked with food and water | |||

* many shelters had no trained manager | |||

* less than 2% of homeowners with suitable homes | |||

for shelters had written for plans to upgrade | |||

* rural areas typically had one shelter space for | |||

every four people | |||

In 1973 a group of forty-five volunteers training, under the supervision of the [[DUBUQUE POLICE DEPARTMENT]] four hours each month, comprised the Dubuque Civil Defense Auxiliary Police. They were supplements to the police in emergencies such as traffic or crowd control. Other duties included patrolling the city in their own cars and reporting any suspicious activity. They paid for their own uniforms as well as the gasoline and oil used on patrol. They were not armed and did not play a role in arresting or questioning suspects. (8) | |||

See: [[GROUND OBSERVER CORPS]] | See: [[GROUND OBSERVER CORPS]] | ||

| Line 18: | Line 37: | ||

1. "Alert 'Bombs' Miss Dubuque," ''Telegraph Herald'', September 12, 1957, p. 1 | 1. "Alert 'Bombs' Miss Dubuque," ''Telegraph Herald'', September 12, 1957, p. 1 | ||

2. "Iowans Better Prepared for Natural Disaster," ''Telegraph Herald'', May 31, 1972, p. 6 | 2. "Fallout Shelter Signs," ''Telegraph Herald'', December 6, 1962, p. 16 | ||

3. "Mine Fallout Shelter Biggest in Tri-States," ''Telegraph Herald,'' June 9, 1963, p. 37 | |||

4. "Iowans Better Prepared for Natural Disaster," ''Telegraph Herald'', May 31, 1972, p. 6 | |||

5. "Iowa Survey of Homes Begun to Find More Fallout Shelters," ''Telegraph Herald'', April 3, 1967, p. 11 | |||

6. Hansen, Christine, "Disaster Warning Systems Lacking," ''Telegraph Herald'', June 6, 1968, p. 16 | |||

7. "Civil Defense 'Falls Down' On Fallouts," ''Telegraph Herald,'' May 7 1969, p. 10 | |||

8. "Action Line," ''Telegraph Herald'', March 21, 1973, p. 22 | |||

[[Category: Events]] | [[Category: Events]] | ||

[[Category: Organizations]] | [[Category: Organizations]] | ||

Revision as of 21:01, 3 June 2017

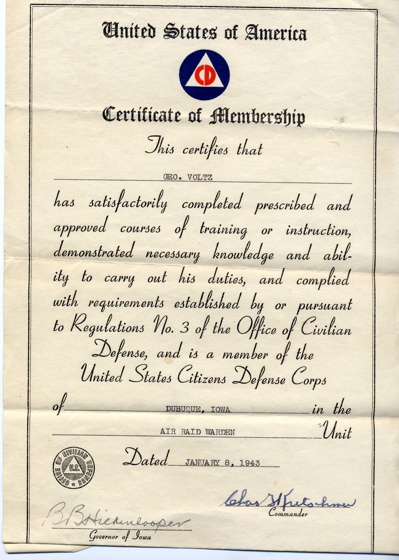

CIVIL DEFENSE. For the history of Civil Defense in the United States, see: http://www.civildefensemuseum.com/history.html

In 1957 Dubuque was not one of the cities "hit" by hypothetical atomic bombs during Operation Alert. This was fortunate because the city did not have a Civil Defense director or a working disaster plan.

In Operation Alert, Iowa Civil Defense headquarters in Des Moines received a call that enemy plane were sighted over Alaska. State headquarters phoned other cities in the state. At 11:15 a.m. sirens began blasting away and remained going for ten minutes. When it was learned that Dubuque was not "hit," the city was to assume a support role. City manager Laverne Schiltz opened a letter at 1:00 p.m. which told him of "Dubuque's fate." (1)

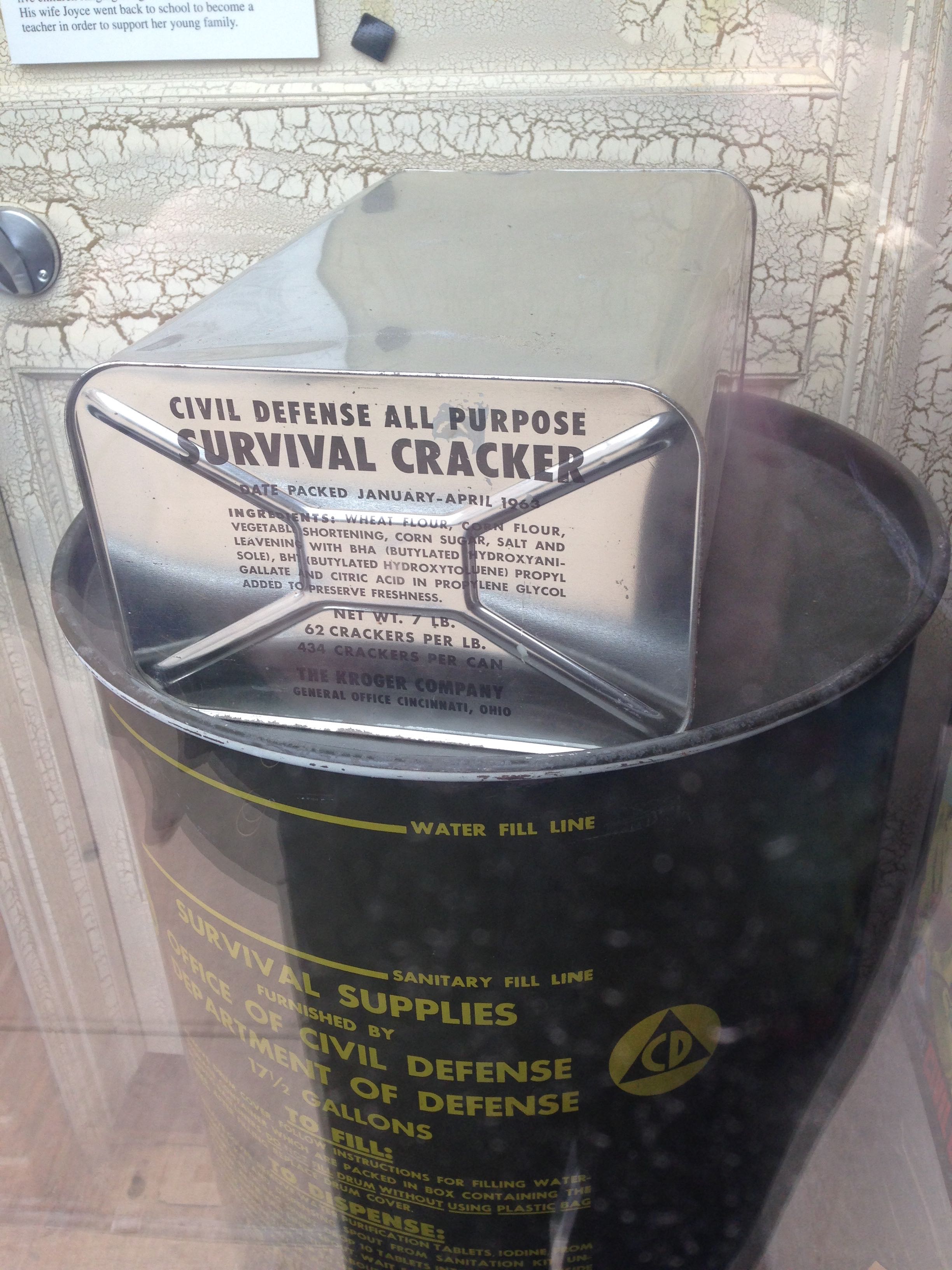

The 1961 Berlin Crisis and the Kennedy administration's reorganization of the national civil defense program led to an emphasis on a network of fallout shelter. While not designed to protect those inside against the blast itself, the shelters were meant to save lives during the following weeks with supplies of food and water.

The first yellow-and-black civil defense fallout shelter signs were posted on December 5, 1962 on the doorways to official fallout shelters in Dubuque buildings. (2) The largest natural fallout shelter was located near Clayton, Iowa. Established in a silica mine, the shelter was stocked in 1963 with 500,000 pounds of supplies including 220,104 pounds of survival crackers, 154,000 gallons of water, and 881 medical kits. It was estimated that 44,016 people could be supplied for two weeks. The figure could be raised to 78,000 with a system of forced air ventilation. (3)

In 1966, the Iowa law allowing the civil defense department to plan for natural disasters as well s nuclear attack was passed. (4)

The Iowa Civil Defense Division began a program in April, 1967 to find an additional 2 million fallout shelter spaces in the state. While a group of fourteen women were interviewing homeowners in rural areas, citizens of Dubuque and large cities received questionnaires. Once these were returned an evaluated, the homeowner would receive a "protection factor" indicating how well the residents would be shielded after a nuclear attack. The reply would also indicated what part of the home would be the best for shelter. (5)

In 1968 Dubuque was one of the few towns in the Tri-State area to have a Civil Defense warning siren and a carefully planned warning system. The Dubuque weather bureau was responsible for contacting adjoining counties with disaster warnings and alerts through the Dubuque County sheriff's office. There was a county-wide system of spotters living within a five-mile radius of a community in Dubuque County with the responsibility of notifying their town's Civil Defense officials if they saw funnel clouds or other signs of bad weather. George Orr, the Iowa Civil Defense Director, stated that city officials were reluctant to spend the money on tornado warning systems. This was despite the fact that a city installing an system would receive half of the cost reimbursed by the federal government. (6)

In 1969 the fallout program championed in 1961 offered little. A study indicated that: (7)

* 40% of the shelters were not marked

* only 50% were stocked with food and water

* many shelters had no trained manager

* less than 2% of homeowners with suitable homes

for shelters had written for plans to upgrade

* rural areas typically had one shelter space for

every four people

In 1973 a group of forty-five volunteers training, under the supervision of the DUBUQUE POLICE DEPARTMENT four hours each month, comprised the Dubuque Civil Defense Auxiliary Police. They were supplements to the police in emergencies such as traffic or crowd control. Other duties included patrolling the city in their own cars and reporting any suspicious activity. They paid for their own uniforms as well as the gasoline and oil used on patrol. They were not armed and did not play a role in arresting or questioning suspects. (8)

---

Source:

1. "Alert 'Bombs' Miss Dubuque," Telegraph Herald, September 12, 1957, p. 1

2. "Fallout Shelter Signs," Telegraph Herald, December 6, 1962, p. 16

3. "Mine Fallout Shelter Biggest in Tri-States," Telegraph Herald, June 9, 1963, p. 37

4. "Iowans Better Prepared for Natural Disaster," Telegraph Herald, May 31, 1972, p. 6

5. "Iowa Survey of Homes Begun to Find More Fallout Shelters," Telegraph Herald, April 3, 1967, p. 11

6. Hansen, Christine, "Disaster Warning Systems Lacking," Telegraph Herald, June 6, 1968, p. 16

7. "Civil Defense 'Falls Down' On Fallouts," Telegraph Herald, May 7 1969, p. 10

8. "Action Line," Telegraph Herald, March 21, 1973, p. 22