Encyclopedia Dubuque

"Encyclopedia Dubuque is the online authority for all things Dubuque, written by the people who know the city best.”

Marshall Cohen—researcher and producer, CNN

Affiliated with the Local History Network of the State Historical Society of Iowa, and the Iowa Museum Association.

LABOR MOVEMENT and TELEVISION: Difference between pages

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Image: | [[Image:jerroldjl.jpg|left|thumb|200px|Photo courtesy: Jim Lang]]TELEVISION. Dubuque's hilly terrain made it a prime candidate for cable television in the early years of the industry. In 1991 cable television had gained 93 percent of the households with television as subscribers. This compared with a national average of 59 percent. | ||

[[Image:rotor.png|left|thumb|200px|Rotor used to rotate a television antenna from within a house.]] | |||

The top news story of 1950 was the bringing of "piped-in" television to Dubuque. Don Ameche's sons attended school in Dubuque when the co-axial cable was introduced. According to the Pittsburg-Press, Don worked better knowing his sons could watch him working "live" on television. (1) Jerrold, Philadelphia-based company, applied on May 24 for a franchise to provide cable television to the city. Four days later two Dubuque television dealers also filed. An impartial study of the two companies was made by Town and Hughes, two Iowa State College engineers. The city council rejected the engineers' recommendation of Jerrold and called a franchise election for Dubuque Community, the local firm, on September 13th. The Jerrold group countered with a petition and won a right for a franchise election on October 11th. A fight was waged in newspaper advertisements and over the radio with a debate held in the Eagles Hall. Dubuque voters went more than four to one against Dubuque Community in the first election. In the second election, the vote was 4,560 to 1,057 approving the franchise for Jerrold. (2) | |||

Dubuque-Jerrold, a subsidiary of a Philadelphia company, was granted the first franchise in the largest turnout of voters in any recent city election at the time. This company had been in competition with a local corporation-the Dubuque Community TV cable company--which had been endorsed by the city council. The first subscriber was hooked up to the system of five television stations in May 1955. It was found that as a direct result of the street system, a radial web with the center at 1043 Main Street would reduce the number of amplifiers needed. (3) Miles of coaxial cable were strung on existing power poles to connect the main office at 1043 Main which housed the electronics equipment needed to convert and distribute the TV signal to a 421-foot tower in St. Catherine, Iowa. (4) The city was divided into six areas for service. It was expected that Area One from Dodge Street to 18th street and between Bluff and the river would take five weeks for completion. (5) | |||

Viewers in Area I were able to enjoy cable television on May 9, 1955. They had their choice of five "snow-free" stations. There were two CBS channels (WMT-2 and WHBF-4); two NBC channels (WOC-6 and KWWL-7) and two ABC channels (KCRG-9 and WREX-13). (6) More than sixty miles of cable had to be strung and approximately fifty amplifiers had to be installed to make that evening possible. Mounted on the tower near St. Catherine were five specially constructed antennas used to capture the five different frequencies transported on the system. Channel Two broadcast from Cedar Rapids was picked up on an antenna about seventy-five feet above the ground. Channel 9, the weakest of the signals picked up, was captured by an antenna near the tower's peak. It was thought possible that an extension on the tower would allow signals to be received from Chicago. Getting the signal throughout the city required poles which were shared by [[INTERSTATE POWER COMPANY]] and Northwestern Bell Telephone. In some cases the other companies had to move their lines to keep the TV cables at legal distances from other lines. There were also instances when poles had to be replaced. Even with the first cable television available, engineers for Jerrod were solving problems of interference from other signals. (7) | |||

In 1963 MEDELCO completed the installation of cable-powered television in all three Dubuque hospitals. Families with patients in the hospital could ask the hospital office staff to have to have a cable-powered television installed in the room with no deposit, minimum time contract and "reasonable rates." (8) On November 5, 1963 local residents were asked to vote on Franchise Ordinance No. 25-63, as enacted by the city council on September 16, 1963. Viewers with the cable television could watch ABC, CBS, NBC and WGN Chicago television which offered Family Classics as a regular Friday night feature. There was also 24-hours of the "world's great music over crustal-clear FM stations, and thrilling FM stereo broadcasts." (9) | |||

On December 29, 1968 Dubuque television viewers experienced the first citywide breakdown since 1954 when cable came to Dubuque. According to Dubuque TV-FM Cable Company authorities the cable contracted in extremely cold weather. That evening the sudden drop in temperature caused the wires to contract so rapidly that a splice in the line pulled apart. Workers were out until midnight attempting to find the break, but quit due to the cold (-17 degrees). They resumed in the morning and discovered the break about 8:30 a.m. (10) | |||

In 1969, WNIC-TV went on the air in the Dubuque as the city's only private television station. It was named after its owner and producer, 13-year old [[SCHRUP, Nicholas III|Nicholas SCHRUP III]]. Schrup earned the money for the equipment by selling coffee grinders door to door. He operated the station out of the basement of his home at 330 Wartburg Place. | |||

In 1971 the Federal Communication Commission announced its intent to require cable television to make channels available for public use as early as March 1, 1972. While this might have surprised others, Robert Loos, general manager of the Dubuque TV-FM Cable Company and local public and parochial school administrators had been discussing such a possibility. While greatly interested in the concept, administrators were concerned that school systems did not have the money for expensive equipment. Loos noted that the cable company were not demanding that broadcasts for educational enrichment be on professional quality. The FCC was also interested in providing channels of municipal use and one for use by the general public. Locally, this was a problem because the cable system was only a 12-channel system while other had a capacity for twenty channels. (11) | |||

In 1976 Dubuque was one of the first cities in the country to offer Home Box Office access. The same year the cable company constructed the first satellite receiving station in Iowa. Showtime replaced HBO in 1979. When the system was rebuilt in 1981 to accommodate thirty-five channels it was considered state-of-the-art television technology. In 1988, fifty-one channels were available. | |||

The early history of cable television in Dubuque was marked by buyouts and mergers that resulted in new owners for the Dubuque franchise. These changes in ownership were given relatively little attention in comparison with procedures in place in 1991. Regional or local companies that furnished cable service to Dubuque have included H&B Communications and Dubuque TV-FM Cable. Teleprompter, the first national multiple system owner, took over the Dubuque franchise in 1972. Westinghouse bought Teleprompter and renamed it Group W in 1981. | |||

In 1986, when Westinghouse decided to sell off its cable division, Group W was the third largest cable television operation in the nation. Too large for any one company to purchase the entire operation, Group W was purchased by a group of five companies which then divided the company into separate territories. Tele-Communications, Inc., better known as TCI Cable Company, announced its plans to acquire the rights in 1986 and completed the process in June 1987. | |||

Group W provided a basic thirty channels, five premium pay services, and [[COMMUNITY ACCESS PROGRAMMING]] with studios and equipment considered to be some of nation's finest. By September 1988,fifty-one channels were available to Dubuque viewers with a planned sixty-four channels to be available by September 1991. | |||

"Cable television pirates" were pursued by TeleprompTer TV-FM Cable Company in 1981. The problem was not new. In August, 1977 a special amnesty program by Dubuque's Teleprompter Cable resulted in 203 residents confessing to pirating cable service. (12) In 1981, six or seven independent operators advertised by word-of-mouth that they would connect homes to cable for a one-time-charge and no monthly bills. A reward of $100 was offered for the arrest and conviction of anyone found involved in such a business. "Stealing" cable signals was just as illegal as other types of theft. At the time, Teleprompter was getting $7.25 per month for basic service and $9.95 for the Showtime movie and entertainment service beyond the cost of the initial installation. (13) | |||

In 1981 the authority to regulate basic cable rates was written into the Dubuque cable franchise. In 1984, Congress, however, passed the Cable Communication Act which pre-empted rate regulation and major provisions of local franchises across the United States. Since that date, Dubuque gained a national reputation for its fight to maintain local rate regulatory power. In July 1990 the Federal Communications Commission ruled TCI Cablevision, the city's cable operator, had no effective local market competition and therefore restored limited basic rate regulation authority to the city. (14) This special provision to cable television regulation was known as the "Tauke Amendment" because it was first promoted by U. S. Representative [[TAUKE, Thomas|Thomas TAUKE]]. (15) | |||

By 1991 the cable television industry in Dubuque was monitored by two commissions. The Cable Television Regulatory Commission, comprised of five citizen members, had the responsibility of franchise enforcement and settling disputes. The Cable Community Teleprogramming Commission, made up of nine members, had the responsibility to oversee the general policy and performance of the educational and public access channels. | |||

The Regulatory Commission responded in 1991 to a proposed TCI billing promotion which also drew the attention of the Iowa Attorney General's office. TCI subscribers were given a free month of a premium movie channel called Encore to its system nationwide on June 3. If, at the end of the month, a subscriber chose not to continue receiving the channel a TCI technician would have to come to the residence and manually disconnect the channel at no charge. If they did not call, the consumer would be then be automatically billed for the new service. (16) | |||

In response to the confusing "negative-option" marketing to get subscribers into taking Encore, the Regulatory Commission recommended that the city council enact an ordinance prohibiting the technique. Further, the commission recommended that the council use franchise fee money for "any legal avenues" to protect Dubuque consumers from this technique. (17) A TCI plan to allow customers to deduct the payment from their cable bill rather than calling for disconnection did not satisfy customers or the city council. (18) Acting to end legal issues around the nation, TCI dropped its controversial billing plan in June 1991 and made Encore an optional channel which customers would need to order to receive. (19) | |||

Dubuque's only television station, KDUB, was founded by the Dubuque Communication Corporation in 1970. KDUB was originally based in an office building just south of Dubuque, near Key West, Iowa. The station eventually moved into offices on the ninth floor of the former [[ROSHEK'S DEPARTMENT STORE]] and later to 744 Main Street. The station went off the air from 1974 to 1976 because Dubuque Communication Corporation was unable to find a buyer for the financially troubled station. | |||

In 1976 KDUB was sold to the Lloyd Hearing Aid Corporation of Rockford, Illinois, for $35,000. The station operation was moved to the ninth floor of the [[DUBUQUE BUILDING]]. In 1979 the station was purchased for $1.5 million by Birney Imes, Jr., who added it to a group of three other stations he owned. Imes sold KDUB in 1985 to Thomas Bond and six Alabama-based limited partners using the corporate name of Dubuque TV Ltd. for $3.25 million. Bond, formerly a television news anchorman, had been employed as the manager of an Imes television station in Columbus, Mississippi. | |||

In | In May 1986, Group W Cable announced that it would continue network non-duplication protection for KDUB. By blocking the signal whenever identical network programming was being shown from KCRG, a rival ABC affiliate broadcasting from Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Group W protected advertising revenue of the local station. This protection had been mandated until January of 1986 by an order from the Federal Communications Commission. | ||

In December 1987 the sale was announced of KDUB for $4 million to Sage Broadcasting Corporation. Plans were made to expand local news, special programming, and sports in addition to upgrading the station's technical facilities. | |||

In May 1988, TCI Cablevision of Dubuque announced that it would end the non-duplication protection on April 1st, but that it would also move KCRG to Channel 26. This left KDUB as the only ABC affiliate on the low-numbered cable channels. KDUB had previously lost the non-duplication protection from October 1980, through November 1981. At that time the station announced that it had suffered a loss of $100,000 in advertising revenue. | |||

Sale of the Dubuque station, however, was stopped after KCRG filed two petitions with the Federal Communications Commission stating that Dubuque Television Partnership was unfit to hold the license. In January 1988, KCRG charged that KDUB with TCI Cablevision of Dubuque had conspired to limit KCRG's access to the Dubuque market by using the blackout of KCRG's signal. When the FCC approved the license transfer on January 19, 1989, KCRG filed an application for review. | |||

On March 17, 1989, the FCC approved the sale of KDUB. The next day, despite the favorable ruling from the FCC, it was announced the Dubuque station would not be sold; stating the delays in the FCC ruling had caused Sage Broadcasting to withdraw its offer. On April 10, 1990, KDUB sued KCRG in a $4 million lawsuit alleging that KCRG management had intentionally delayed the sale of the station, leading to the offer being withdrawn. The suit further stated that KCRG had unsuccessfully attempted to purchase KDUB in August 1987, for $2.4 million. | |||

In | [[Image:kfxb.jpg|left|thumb|200px|744 Main Street in 2010]]In 1995, the KDUB entered into a management agreement with Second Generation of Iowa, owner of Cedar Rapids Fox affiliate KFXA (Channel 28). It was decided to discontinue the ABC affiliation and convert KDUB to a semi-satellite of KFXA, under the call letters KFXB; most programming was simulcast from KFXA, but KFXB would continue its news operation (at that time, KFXA had no newscast at all). Prior to this, the Fox network feed was re-transmitted on the Dubuque cable system on Channel 13. After a few years, it was decided to close down the Dubuque news operation. This made KFXB a full satellite of KFXA. During this time the stations identified themselves as "KFXA-KFXB Fox 28/40." | ||

Limited choice for viewers in Dubuque was a problem for many years. In 1983 Group W tried an experimental pay-per-view broadcast of a WBA junior welterweight championship rematch. Group W needed to sell an estimated 750 converter units at $19.95 to make a profit. It sold only fifty. The memory of the experience lasted and in 1991 TCI officials were still doubting enough interest existed in Dubuque for the service. Those who wanted to see main events broadcast from Las Vegas needed to pay $20 per person and go to [[FIVE FLAGS CIVIC CENTER]] where broadcasts could be seen on a large screen television. (20) | |||

TCI Cablevision officials announced in April 1991 that they had signed an agreement by which TCI cable would become a Fox Network affiliate. The FOX NET system would supply affiliates with an 18-hour-per-day program including Fox primetime programming, Fox Children's Network, and additional programming from the Fox film and television library. TCI would pay Fox a monthly per-scriber fee. TCI would have to rearrange its channels to include the new channel in its current 47-channel basic service. One over-the-air broadcast station, KOCR-TV of Cedar Rapids, carried Fox programming and had installed a low-power transmitter to air its signal on UHF channel 51 to Dubuque viewers. City officials, however, stated that the signal was too weak to be received by most city residents. (21) In July, 1991 KOCR-TV was "unplugged" due to its failure to pay rent. (22) | |||

The | The TCI expanded programming debuted on October 1, 1991. Subscribers were able to access home shopping networks, foreign movies, religious programming and more music videos. The new line-up offered sixty channel basic service. (23) That franchise agreement, however, came back to negatively affect Dubuque residents. Beginning in early April, 1993, Dubuque cable subscribers faced a channel realignment affecting 36 channels. The realignment resulted from TCI grouping together certain channels to make it easier to market. Nationwide, TCI was planning to offer a basic level cable service for $10 per month that would include local broadcast stations and public-access channels. An additional charge would be made to include advertiser-supported cable networks like CNN and ESPN. Since the Dubuque franchise called for sixty channels in a basic package, residents in the city did not qualify for the $10 charge. (24) In 1993 a nationwide 10% cut in basic cable costs did not benefit Dubuque subscribers either. (25) | ||

Subscribers wanting to see movies without going to the video store could begin receiving them over TCI cable on June 16, 1993. Pay-per-view movies, which could be ordered from home, cost $3.99 each. A special converter was needed which was already available to users who received premium channels like HBO or Cinemax. Converters could also be rented for $4.95 per month. This fee could be avoided if two movies were ordered each month. (26) | |||

In a move that surprised communications watchers who felt that cable television and telephone companies would be competitors, Bell Atlantic announced on October 13, 1993 that it would buy TCI. Regulatory changes, however, allowed the two to become allies. (27) | |||

Beginning on January 1, 1998 cable subscribers in Dubuque, Asbury, Sageville and most of rural Dubuque County could subscribe to TCI Cable. For $13.30 per month, customers could receive up to 36 more video channels. Customers who subscribed to the premium movie services also received additional channels. Due to TCI's use of digital compression technology more channels could be squeezed into a broad-band cable. The service was carried through existing cable into the home where it was converted by a digital compression terminal that sat on the television set. Customers did not need a digital television set to receive digital cable. TCI Digital Cable customers would continue to receive local networks and independent stations. Installation cost $12.50 including a phone line. (28) | |||

In March, 1998 voters in Dubuque approved giving McLeod-USA the chance to offer cable television in competition with TCI. McLeod had been offering local telephone service to Dubuque customers since July 1997. (29) | |||

In 2004, KFXB's owners, Dubuque TV Limited Partnership sold the station to the Christian Television Network, who switched the station to its primarily-religious programming. Fox programming continued to be transmitted on KFXA - which operated as the primary Fox affiliate for northeast Iowa. At this time KFXB lost its longstanding Channel 4 assignment on the Dubuque cable system to KFXA, with KFXB being moved to channel 14. | |||

KFXB added cable coverage of the Cedar Rapids and Iowa City areas on Mediacom cable in 2005. | |||

--- | --- | ||

| Line 240: | Line 72: | ||

Source: | Source: | ||

1. | 1. Steinhauser, Si. "Originals to Be Heard, Not Seen," ''Pittsburgh Press'', December 13, 1950, p. 10. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1144&dat=19501213&id=sXgbAAAAIBAJ&sjid=ak0EAAAAIBAJ&pg=2912,6710013&hl=en | ||

10 | |||

2. "Television Cable Argument Rated Top Dubuque News Story of Year," ''Telegraph Herald'', January 2, 1955 Dubuque News, p. 1 | |||

3. Talbott, Douglas. "Topography of City Teachers Useful Lesson, ''The Telegraph-Herald'', May 8, 1955, p. 8 | |||

4. "TV Cable Stringing Expected to Start This Week; Areas Named," ''Telegraph Herald,'' January 16, 1955, Dubuque News, p. 1 | |||

5. Ibid. | |||

6. "Dubuque in the 1950s," '''Dubuque by the Decades''', ''Telegraph Herald'', July, 2020, p. 22 | |||

7. "Area I Subscribers Will Enjoy Cable TV Monday," ''Telegraph Herald'', May 8, 1955, p. 14 | |||

8. Advertisement, ''Telegraph-Herald'', May 5, 1963, p. 20 | |||

9. Advertisement, ''Telegraph-Herald'', November 4, 1963, p. 5 | |||

10. "Cable TV Knocked Out," ''Telegraph-Herald'', December 30, 1968, p. 1 | |||

11. Babcock, Susan, "CATV and School," Telegraph Herald, September 27, 1971, p. 6 | |||

12. Day, Mike, "Research Reveals Odd Occurrences in Late '70s," Telegraph Herald, December 19, 2021, p. 10A | |||

13. Hogstrom, Erik, "1981: Cable Provider Takes Aim at Piracy," '''Telegraph Herald''', Dec. 10, 2021, p. 6A | |||

14. Arnold, Bill. "TCI Cable Battle Refought Nationally," ''Telegraph Herald'', June 13, 1991, p. 1 | |||

15. Webber, Steve. "Cable Bill with Dubuque Provision Survives Round," ''Telegraph Herald'', June 17, 1992, p. 3A | |||

16. Arnold, Bill."Cable Bill Procedure Probed," ''Telegraph Herald'', May 15, 1991, p. 1 | |||

17. Arnold, Bill. "Panel: Ban TCI Billing Plan," ''Telegraph Herald'', May 29, 1991 | |||

18. Gilson, Donna. "TCI Backs Down on Encore Channel," ''Telegraph Herald,'' June 11, 1991, p. 1 | |||

19. "TCI to Handle 'Encore' as Optional Channel," Telegraph Herald, June 14, 1991, p. 3A | |||

20. Arnold, Bill. "TCI Official: Not Enough Interest in Trying Pay-Per-View Service," ''Telegraph Herald'', March 18, 1991, p. 3A | |||

21. Arnold, Bill. "Fox Network Signs With TCI," ''Telegraph Herald'', April 2, 1991, p. 3A | |||

22. Arnold, Bill. "KOCR's Plug Pulled; Failure to Pay Rent Cited," ''Telegraph Herald'', July 4, 1991, p. 3A | |||

23. Dickel, Dean. "Channels to Debut October 1, 1991," ''Telegraph Herald'', September 7, 1991, p. 1 | |||

24. Arnold, Bill. "TCI Cablevision to Adjust Basic Service," ''Telegraph Herald'', January 14, 1993, p. 3A | |||

25. Arnold, Bill. "Cable Ruling Won't Affect Dubuque," ''Telegraph Herald'', April 2, 1993, p. 3A | |||

26. Eiler, Donnelle. "TCI Begins Pay-Per-View Movie Service," ''Telegraph Herald'', June 16, 1993, p. 3A | |||

27. "Bell Atlantic, TCI to Merge," ''Telegraph Herald'', October 13, 1993, p. 1 | |||

28. Bergstrom, Kathy. "TCI Announces Digital Service," ''Telegraph Herald'', January 9, 1998, p. 3A. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=aEyKTaVlRPYC&dat=19980109&printsec=frontpage&hl=en | |||

29. Wilkinson, Jennifer. "McLeod Ponders Cable TV Service," ''Telegraph Herald'', March 21, 1998, p. 1. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=aEyKTaVlRPYC&dat=19980321&printsec=frontpage&hl=en | |||

[[Category: | [[Category: Industry]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category: Media]] | ||

Latest revision as of 03:49, 20 December 2021

TELEVISION. Dubuque's hilly terrain made it a prime candidate for cable television in the early years of the industry. In 1991 cable television had gained 93 percent of the households with television as subscribers. This compared with a national average of 59 percent.

The top news story of 1950 was the bringing of "piped-in" television to Dubuque. Don Ameche's sons attended school in Dubuque when the co-axial cable was introduced. According to the Pittsburg-Press, Don worked better knowing his sons could watch him working "live" on television. (1) Jerrold, Philadelphia-based company, applied on May 24 for a franchise to provide cable television to the city. Four days later two Dubuque television dealers also filed. An impartial study of the two companies was made by Town and Hughes, two Iowa State College engineers. The city council rejected the engineers' recommendation of Jerrold and called a franchise election for Dubuque Community, the local firm, on September 13th. The Jerrold group countered with a petition and won a right for a franchise election on October 11th. A fight was waged in newspaper advertisements and over the radio with a debate held in the Eagles Hall. Dubuque voters went more than four to one against Dubuque Community in the first election. In the second election, the vote was 4,560 to 1,057 approving the franchise for Jerrold. (2)

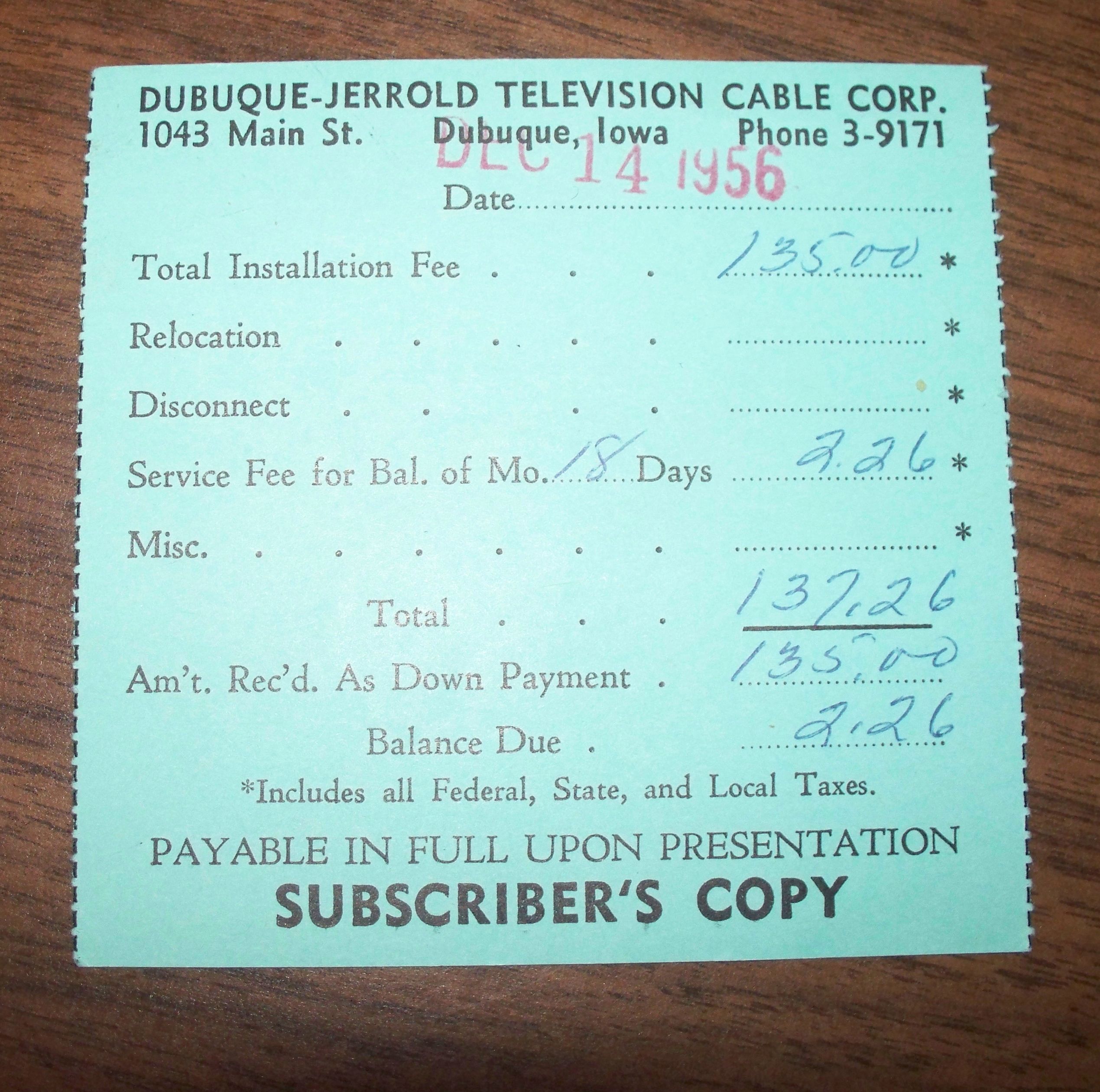

Dubuque-Jerrold, a subsidiary of a Philadelphia company, was granted the first franchise in the largest turnout of voters in any recent city election at the time. This company had been in competition with a local corporation-the Dubuque Community TV cable company--which had been endorsed by the city council. The first subscriber was hooked up to the system of five television stations in May 1955. It was found that as a direct result of the street system, a radial web with the center at 1043 Main Street would reduce the number of amplifiers needed. (3) Miles of coaxial cable were strung on existing power poles to connect the main office at 1043 Main which housed the electronics equipment needed to convert and distribute the TV signal to a 421-foot tower in St. Catherine, Iowa. (4) The city was divided into six areas for service. It was expected that Area One from Dodge Street to 18th street and between Bluff and the river would take five weeks for completion. (5)

Viewers in Area I were able to enjoy cable television on May 9, 1955. They had their choice of five "snow-free" stations. There were two CBS channels (WMT-2 and WHBF-4); two NBC channels (WOC-6 and KWWL-7) and two ABC channels (KCRG-9 and WREX-13). (6) More than sixty miles of cable had to be strung and approximately fifty amplifiers had to be installed to make that evening possible. Mounted on the tower near St. Catherine were five specially constructed antennas used to capture the five different frequencies transported on the system. Channel Two broadcast from Cedar Rapids was picked up on an antenna about seventy-five feet above the ground. Channel 9, the weakest of the signals picked up, was captured by an antenna near the tower's peak. It was thought possible that an extension on the tower would allow signals to be received from Chicago. Getting the signal throughout the city required poles which were shared by INTERSTATE POWER COMPANY and Northwestern Bell Telephone. In some cases the other companies had to move their lines to keep the TV cables at legal distances from other lines. There were also instances when poles had to be replaced. Even with the first cable television available, engineers for Jerrod were solving problems of interference from other signals. (7)

In 1963 MEDELCO completed the installation of cable-powered television in all three Dubuque hospitals. Families with patients in the hospital could ask the hospital office staff to have to have a cable-powered television installed in the room with no deposit, minimum time contract and "reasonable rates." (8) On November 5, 1963 local residents were asked to vote on Franchise Ordinance No. 25-63, as enacted by the city council on September 16, 1963. Viewers with the cable television could watch ABC, CBS, NBC and WGN Chicago television which offered Family Classics as a regular Friday night feature. There was also 24-hours of the "world's great music over crustal-clear FM stations, and thrilling FM stereo broadcasts." (9)

On December 29, 1968 Dubuque television viewers experienced the first citywide breakdown since 1954 when cable came to Dubuque. According to Dubuque TV-FM Cable Company authorities the cable contracted in extremely cold weather. That evening the sudden drop in temperature caused the wires to contract so rapidly that a splice in the line pulled apart. Workers were out until midnight attempting to find the break, but quit due to the cold (-17 degrees). They resumed in the morning and discovered the break about 8:30 a.m. (10)

In 1969, WNIC-TV went on the air in the Dubuque as the city's only private television station. It was named after its owner and producer, 13-year old Nicholas SCHRUP III. Schrup earned the money for the equipment by selling coffee grinders door to door. He operated the station out of the basement of his home at 330 Wartburg Place.

In 1971 the Federal Communication Commission announced its intent to require cable television to make channels available for public use as early as March 1, 1972. While this might have surprised others, Robert Loos, general manager of the Dubuque TV-FM Cable Company and local public and parochial school administrators had been discussing such a possibility. While greatly interested in the concept, administrators were concerned that school systems did not have the money for expensive equipment. Loos noted that the cable company were not demanding that broadcasts for educational enrichment be on professional quality. The FCC was also interested in providing channels of municipal use and one for use by the general public. Locally, this was a problem because the cable system was only a 12-channel system while other had a capacity for twenty channels. (11)

In 1976 Dubuque was one of the first cities in the country to offer Home Box Office access. The same year the cable company constructed the first satellite receiving station in Iowa. Showtime replaced HBO in 1979. When the system was rebuilt in 1981 to accommodate thirty-five channels it was considered state-of-the-art television technology. In 1988, fifty-one channels were available.

The early history of cable television in Dubuque was marked by buyouts and mergers that resulted in new owners for the Dubuque franchise. These changes in ownership were given relatively little attention in comparison with procedures in place in 1991. Regional or local companies that furnished cable service to Dubuque have included H&B Communications and Dubuque TV-FM Cable. Teleprompter, the first national multiple system owner, took over the Dubuque franchise in 1972. Westinghouse bought Teleprompter and renamed it Group W in 1981.

In 1986, when Westinghouse decided to sell off its cable division, Group W was the third largest cable television operation in the nation. Too large for any one company to purchase the entire operation, Group W was purchased by a group of five companies which then divided the company into separate territories. Tele-Communications, Inc., better known as TCI Cable Company, announced its plans to acquire the rights in 1986 and completed the process in June 1987.

Group W provided a basic thirty channels, five premium pay services, and COMMUNITY ACCESS PROGRAMMING with studios and equipment considered to be some of nation's finest. By September 1988,fifty-one channels were available to Dubuque viewers with a planned sixty-four channels to be available by September 1991.

"Cable television pirates" were pursued by TeleprompTer TV-FM Cable Company in 1981. The problem was not new. In August, 1977 a special amnesty program by Dubuque's Teleprompter Cable resulted in 203 residents confessing to pirating cable service. (12) In 1981, six or seven independent operators advertised by word-of-mouth that they would connect homes to cable for a one-time-charge and no monthly bills. A reward of $100 was offered for the arrest and conviction of anyone found involved in such a business. "Stealing" cable signals was just as illegal as other types of theft. At the time, Teleprompter was getting $7.25 per month for basic service and $9.95 for the Showtime movie and entertainment service beyond the cost of the initial installation. (13)

In 1981 the authority to regulate basic cable rates was written into the Dubuque cable franchise. In 1984, Congress, however, passed the Cable Communication Act which pre-empted rate regulation and major provisions of local franchises across the United States. Since that date, Dubuque gained a national reputation for its fight to maintain local rate regulatory power. In July 1990 the Federal Communications Commission ruled TCI Cablevision, the city's cable operator, had no effective local market competition and therefore restored limited basic rate regulation authority to the city. (14) This special provision to cable television regulation was known as the "Tauke Amendment" because it was first promoted by U. S. Representative Thomas TAUKE. (15)

By 1991 the cable television industry in Dubuque was monitored by two commissions. The Cable Television Regulatory Commission, comprised of five citizen members, had the responsibility of franchise enforcement and settling disputes. The Cable Community Teleprogramming Commission, made up of nine members, had the responsibility to oversee the general policy and performance of the educational and public access channels.

The Regulatory Commission responded in 1991 to a proposed TCI billing promotion which also drew the attention of the Iowa Attorney General's office. TCI subscribers were given a free month of a premium movie channel called Encore to its system nationwide on June 3. If, at the end of the month, a subscriber chose not to continue receiving the channel a TCI technician would have to come to the residence and manually disconnect the channel at no charge. If they did not call, the consumer would be then be automatically billed for the new service. (16)

In response to the confusing "negative-option" marketing to get subscribers into taking Encore, the Regulatory Commission recommended that the city council enact an ordinance prohibiting the technique. Further, the commission recommended that the council use franchise fee money for "any legal avenues" to protect Dubuque consumers from this technique. (17) A TCI plan to allow customers to deduct the payment from their cable bill rather than calling for disconnection did not satisfy customers or the city council. (18) Acting to end legal issues around the nation, TCI dropped its controversial billing plan in June 1991 and made Encore an optional channel which customers would need to order to receive. (19)

Dubuque's only television station, KDUB, was founded by the Dubuque Communication Corporation in 1970. KDUB was originally based in an office building just south of Dubuque, near Key West, Iowa. The station eventually moved into offices on the ninth floor of the former ROSHEK'S DEPARTMENT STORE and later to 744 Main Street. The station went off the air from 1974 to 1976 because Dubuque Communication Corporation was unable to find a buyer for the financially troubled station.

In 1976 KDUB was sold to the Lloyd Hearing Aid Corporation of Rockford, Illinois, for $35,000. The station operation was moved to the ninth floor of the DUBUQUE BUILDING. In 1979 the station was purchased for $1.5 million by Birney Imes, Jr., who added it to a group of three other stations he owned. Imes sold KDUB in 1985 to Thomas Bond and six Alabama-based limited partners using the corporate name of Dubuque TV Ltd. for $3.25 million. Bond, formerly a television news anchorman, had been employed as the manager of an Imes television station in Columbus, Mississippi.

In May 1986, Group W Cable announced that it would continue network non-duplication protection for KDUB. By blocking the signal whenever identical network programming was being shown from KCRG, a rival ABC affiliate broadcasting from Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Group W protected advertising revenue of the local station. This protection had been mandated until January of 1986 by an order from the Federal Communications Commission.

In December 1987 the sale was announced of KDUB for $4 million to Sage Broadcasting Corporation. Plans were made to expand local news, special programming, and sports in addition to upgrading the station's technical facilities.

In May 1988, TCI Cablevision of Dubuque announced that it would end the non-duplication protection on April 1st, but that it would also move KCRG to Channel 26. This left KDUB as the only ABC affiliate on the low-numbered cable channels. KDUB had previously lost the non-duplication protection from October 1980, through November 1981. At that time the station announced that it had suffered a loss of $100,000 in advertising revenue.

Sale of the Dubuque station, however, was stopped after KCRG filed two petitions with the Federal Communications Commission stating that Dubuque Television Partnership was unfit to hold the license. In January 1988, KCRG charged that KDUB with TCI Cablevision of Dubuque had conspired to limit KCRG's access to the Dubuque market by using the blackout of KCRG's signal. When the FCC approved the license transfer on January 19, 1989, KCRG filed an application for review.

On March 17, 1989, the FCC approved the sale of KDUB. The next day, despite the favorable ruling from the FCC, it was announced the Dubuque station would not be sold; stating the delays in the FCC ruling had caused Sage Broadcasting to withdraw its offer. On April 10, 1990, KDUB sued KCRG in a $4 million lawsuit alleging that KCRG management had intentionally delayed the sale of the station, leading to the offer being withdrawn. The suit further stated that KCRG had unsuccessfully attempted to purchase KDUB in August 1987, for $2.4 million.

In 1995, the KDUB entered into a management agreement with Second Generation of Iowa, owner of Cedar Rapids Fox affiliate KFXA (Channel 28). It was decided to discontinue the ABC affiliation and convert KDUB to a semi-satellite of KFXA, under the call letters KFXB; most programming was simulcast from KFXA, but KFXB would continue its news operation (at that time, KFXA had no newscast at all). Prior to this, the Fox network feed was re-transmitted on the Dubuque cable system on Channel 13. After a few years, it was decided to close down the Dubuque news operation. This made KFXB a full satellite of KFXA. During this time the stations identified themselves as "KFXA-KFXB Fox 28/40."

Limited choice for viewers in Dubuque was a problem for many years. In 1983 Group W tried an experimental pay-per-view broadcast of a WBA junior welterweight championship rematch. Group W needed to sell an estimated 750 converter units at $19.95 to make a profit. It sold only fifty. The memory of the experience lasted and in 1991 TCI officials were still doubting enough interest existed in Dubuque for the service. Those who wanted to see main events broadcast from Las Vegas needed to pay $20 per person and go to FIVE FLAGS CIVIC CENTER where broadcasts could be seen on a large screen television. (20)

TCI Cablevision officials announced in April 1991 that they had signed an agreement by which TCI cable would become a Fox Network affiliate. The FOX NET system would supply affiliates with an 18-hour-per-day program including Fox primetime programming, Fox Children's Network, and additional programming from the Fox film and television library. TCI would pay Fox a monthly per-scriber fee. TCI would have to rearrange its channels to include the new channel in its current 47-channel basic service. One over-the-air broadcast station, KOCR-TV of Cedar Rapids, carried Fox programming and had installed a low-power transmitter to air its signal on UHF channel 51 to Dubuque viewers. City officials, however, stated that the signal was too weak to be received by most city residents. (21) In July, 1991 KOCR-TV was "unplugged" due to its failure to pay rent. (22)

The TCI expanded programming debuted on October 1, 1991. Subscribers were able to access home shopping networks, foreign movies, religious programming and more music videos. The new line-up offered sixty channel basic service. (23) That franchise agreement, however, came back to negatively affect Dubuque residents. Beginning in early April, 1993, Dubuque cable subscribers faced a channel realignment affecting 36 channels. The realignment resulted from TCI grouping together certain channels to make it easier to market. Nationwide, TCI was planning to offer a basic level cable service for $10 per month that would include local broadcast stations and public-access channels. An additional charge would be made to include advertiser-supported cable networks like CNN and ESPN. Since the Dubuque franchise called for sixty channels in a basic package, residents in the city did not qualify for the $10 charge. (24) In 1993 a nationwide 10% cut in basic cable costs did not benefit Dubuque subscribers either. (25)

Subscribers wanting to see movies without going to the video store could begin receiving them over TCI cable on June 16, 1993. Pay-per-view movies, which could be ordered from home, cost $3.99 each. A special converter was needed which was already available to users who received premium channels like HBO or Cinemax. Converters could also be rented for $4.95 per month. This fee could be avoided if two movies were ordered each month. (26)

In a move that surprised communications watchers who felt that cable television and telephone companies would be competitors, Bell Atlantic announced on October 13, 1993 that it would buy TCI. Regulatory changes, however, allowed the two to become allies. (27)

Beginning on January 1, 1998 cable subscribers in Dubuque, Asbury, Sageville and most of rural Dubuque County could subscribe to TCI Cable. For $13.30 per month, customers could receive up to 36 more video channels. Customers who subscribed to the premium movie services also received additional channels. Due to TCI's use of digital compression technology more channels could be squeezed into a broad-band cable. The service was carried through existing cable into the home where it was converted by a digital compression terminal that sat on the television set. Customers did not need a digital television set to receive digital cable. TCI Digital Cable customers would continue to receive local networks and independent stations. Installation cost $12.50 including a phone line. (28)

In March, 1998 voters in Dubuque approved giving McLeod-USA the chance to offer cable television in competition with TCI. McLeod had been offering local telephone service to Dubuque customers since July 1997. (29)

In 2004, KFXB's owners, Dubuque TV Limited Partnership sold the station to the Christian Television Network, who switched the station to its primarily-religious programming. Fox programming continued to be transmitted on KFXA - which operated as the primary Fox affiliate for northeast Iowa. At this time KFXB lost its longstanding Channel 4 assignment on the Dubuque cable system to KFXA, with KFXB being moved to channel 14.

KFXB added cable coverage of the Cedar Rapids and Iowa City areas on Mediacom cable in 2005.

---

Source:

1. Steinhauser, Si. "Originals to Be Heard, Not Seen," Pittsburgh Press, December 13, 1950, p. 10. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1144&dat=19501213&id=sXgbAAAAIBAJ&sjid=ak0EAAAAIBAJ&pg=2912,6710013&hl=en

2. "Television Cable Argument Rated Top Dubuque News Story of Year," Telegraph Herald, January 2, 1955 Dubuque News, p. 1

3. Talbott, Douglas. "Topography of City Teachers Useful Lesson, The Telegraph-Herald, May 8, 1955, p. 8

4. "TV Cable Stringing Expected to Start This Week; Areas Named," Telegraph Herald, January 16, 1955, Dubuque News, p. 1

5. Ibid.

6. "Dubuque in the 1950s," Dubuque by the Decades, Telegraph Herald, July, 2020, p. 22

7. "Area I Subscribers Will Enjoy Cable TV Monday," Telegraph Herald, May 8, 1955, p. 14

8. Advertisement, Telegraph-Herald, May 5, 1963, p. 20

9. Advertisement, Telegraph-Herald, November 4, 1963, p. 5

10. "Cable TV Knocked Out," Telegraph-Herald, December 30, 1968, p. 1

11. Babcock, Susan, "CATV and School," Telegraph Herald, September 27, 1971, p. 6

12. Day, Mike, "Research Reveals Odd Occurrences in Late '70s," Telegraph Herald, December 19, 2021, p. 10A

13. Hogstrom, Erik, "1981: Cable Provider Takes Aim at Piracy," Telegraph Herald, Dec. 10, 2021, p. 6A

14. Arnold, Bill. "TCI Cable Battle Refought Nationally," Telegraph Herald, June 13, 1991, p. 1

15. Webber, Steve. "Cable Bill with Dubuque Provision Survives Round," Telegraph Herald, June 17, 1992, p. 3A

16. Arnold, Bill."Cable Bill Procedure Probed," Telegraph Herald, May 15, 1991, p. 1

17. Arnold, Bill. "Panel: Ban TCI Billing Plan," Telegraph Herald, May 29, 1991

18. Gilson, Donna. "TCI Backs Down on Encore Channel," Telegraph Herald, June 11, 1991, p. 1

19. "TCI to Handle 'Encore' as Optional Channel," Telegraph Herald, June 14, 1991, p. 3A

20. Arnold, Bill. "TCI Official: Not Enough Interest in Trying Pay-Per-View Service," Telegraph Herald, March 18, 1991, p. 3A

21. Arnold, Bill. "Fox Network Signs With TCI," Telegraph Herald, April 2, 1991, p. 3A

22. Arnold, Bill. "KOCR's Plug Pulled; Failure to Pay Rent Cited," Telegraph Herald, July 4, 1991, p. 3A

23. Dickel, Dean. "Channels to Debut October 1, 1991," Telegraph Herald, September 7, 1991, p. 1

24. Arnold, Bill. "TCI Cablevision to Adjust Basic Service," Telegraph Herald, January 14, 1993, p. 3A

25. Arnold, Bill. "Cable Ruling Won't Affect Dubuque," Telegraph Herald, April 2, 1993, p. 3A

26. Eiler, Donnelle. "TCI Begins Pay-Per-View Movie Service," Telegraph Herald, June 16, 1993, p. 3A

27. "Bell Atlantic, TCI to Merge," Telegraph Herald, October 13, 1993, p. 1

28. Bergstrom, Kathy. "TCI Announces Digital Service," Telegraph Herald, January 9, 1998, p. 3A. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=aEyKTaVlRPYC&dat=19980109&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

29. Wilkinson, Jennifer. "McLeod Ponders Cable TV Service," Telegraph Herald, March 21, 1998, p. 1. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=aEyKTaVlRPYC&dat=19980321&printsec=frontpage&hl=en