Encyclopedia Dubuque

"Encyclopedia Dubuque is the online authority for all things Dubuque, written by the people who know the city best.”

Marshall Cohen—researcher and producer, CNN

Affiliated with the Local History Network of the State Historical Society of Iowa, and the Iowa Museum Association.

ORPHAN TRAINS: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

Dubuque Sunday Herald | Dubuque Sunday Herald | ||

Dubuque, Iowa | Dubuque, Iowa | ||

05 September 1886 | 05 September 1886 | ||

More Little Ones Coming | |||

Agent Curren, of the New York Foundling and Orphan Asylum, to Arrive Here | |||

with Fifty Children for People in this Vicinity. | with Fifty Children for People in this Vicinity. | ||

The Herald is in receipt of a letter form Mr. Robert Curren, agent of the New York Foundling | |||

The Herald is in receipt of a letter form Mr. Robert Curren, agent of the New York | and Orphan Asylum, stating that he will pass through this city on next Thursday, Sept. 9th, | ||

and | |||

with fifty more little children to be given to families at Epworth, Farley, Dyersville, New | with fifty more little children to be given to families at Epworth, Farley, Dyersville, New | ||

Vienna and Luxemburg and a few will also be given to families in Fort Dodge. He adds that | Vienna and Luxemburg and a few will also be given to families in Fort Dodge. He adds that | ||

fifty more will be brought to Iowa the 1st of October and will find homes with families | fifty more will be brought to Iowa the 1st of October and will find homes with families | ||

between Dubuque and Charles City on the Milwaukee and St. Paul road. | between Dubuque and Charles City on the Milwaukee and St. Paul road. (1) | ||

Between 1858 and 1929 an estimated twenty-five homeless children from the streets of New York or the Children's Village (then known as the New York Juvenile Asylum), what is now the New York Foundling Hospital, and the former Orphan Asylum Society of the City of New York, which is now the Graham-Windham Home for Children found a new home in Dubuque. ( | Between 1858 and 1929 an estimated twenty-five homeless children from the streets of New York or the Children's Village (then known as the New York Juvenile Asylum), what is now the New York Foundling Hospital, and the former Orphan Asylum Society of the City of New York, which is now the Graham-Windham Home for Children found a new home in Dubuque. (2) They came by way of the "Orphan Train," a pioneering initiative which led to child welfare reforms, including child labor laws, adoption and the establishment of foster care services, public education, the provision of health care and nutrition and vocational training. (3) | ||

In the 1850s, an estimated 30,000 children known as "street Arabs" were homeless in New York City. ( | In the 1850s, an estimated 30,000 children known as "street Arabs" were homeless in New York City. (4) Ranging in age from about six to eighteen, they lived in New York City's streets and slums with little or no hope of a successful future. Charles Loring Brace, the founder of The Children's Aid Society, believed that there was a way to change the futures of these children. By removing youngsters from the poverty and crime of the city streets and placing them in morally upright farm families, he thought they would have a chance of escaping a lifetime of suffering. (5) | ||

[[File:orphan2.jpg|250px|thumb|left|]]Rev. Loring Brace proposed that homeless children could be sent by train to live and work on farms. They would be placed in homes for free, but they would serve as an extra pair of hands to help with chores. They would not be indentured. Older children were to be paid for their labors. ( | [[File:orphan2.jpg|250px|thumb|left|]]Rev. Loring Brace proposed that homeless children could be sent by train to live and work on farms. They would be placed in homes for free, but they would serve as an extra pair of hands to help with chores. They would not be indentured. Older children were to be paid for their labors. (6) In 1853, Rev. Brace founded the Children's Aid Society to arrange the trips, raise the money, and obtain the legal permissions needed for relocation. (7) | ||

Many agencies nationwide placed children on trains to go to foster homes. The orphans were scrubbed, dressed in new clothes and put aboard a westbound train at Grand Central Station. The children were not told where they were going or why. They had no idea that they were on an ''orphan train'' or that they had become participants in the largest children’s migration in history. ( | Many agencies nationwide placed children on trains to go to foster homes. The orphans were scrubbed, dressed in new clothes and put aboard a westbound train at Grand Central Station. The children were not told where they were going or why. They had no idea that they were on an ''orphan train'' or that they had become participants in the largest children’s migration in history. (8) | ||

Orphan trains stopped at more than forty-five states across the country as well as Canada and Mexico. During the early years, Indiana received the largest number of children. ( | Orphan trains stopped at more than forty-five states across the country as well as Canada and Mexico. During the early years, Indiana received the largest number of children. (9) From 1854 until 1929 an estimated more than 250,000 children were placed. (10) Between 1858 and 1910, a total of 6,675 children found new homes in Iowa. (11) Generally smaller towns were chosen for the children, but cities like Cedar Rapids and Dubuque are believed to each have become the homes of as many as twenty-five. (12) | ||

A compiled list of people coming to Dubuque was developed by Madonna Harm over many years. ( | A compiled list of people coming to Dubuque was developed by Madonna Harm over many years. (13) The following lists the orphan's actual name (or * adopted name), date of arrival, and person who took the child. | ||

George J. Augmeier June 13, 1872 James Rea | George J. Augmeier June 13, 1872 James Rea | ||

| Line 84: | Line 78: | ||

James Paul Wilson Unknown | James Paul Wilson Unknown | ||

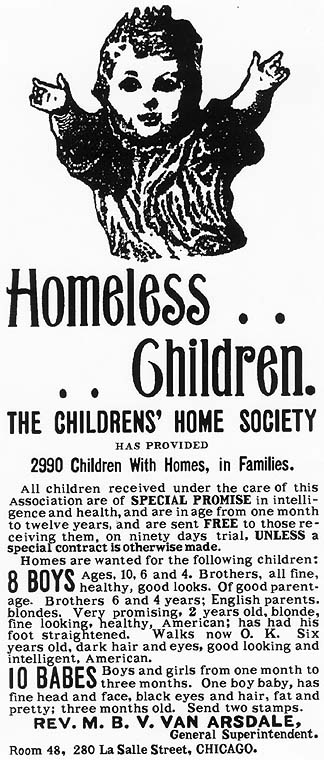

[[File:orphan3.jpg|250px|thumb|left|]]Placement into new families was casual at best. Handbills announced the arrival of the needy children. As the trains pulled into towns, the youngsters were cleaned up and paraded before crowds of "prospective parents." ( | [[File:orphan3.jpg|250px|thumb|left|]]Placement into new families was casual at best. Handbills announced the arrival of the needy children. As the trains pulled into towns, the youngsters were cleaned up and paraded before crowds of "prospective parents." (14) In later years, "parents" wrote to the New York agencies requesting a certain sex, age, hair and eye color. (15) Some of the children struggled in their new surroundings. Children could live with a family for several months and then be sent back to the orphanage. (16) Others went on to lead normal lives. Although records were not always well kept, some of the children placed in the West went on to great successes. There were two governors, one congressman, one sheriff, two district attorneys, three county commissioners as well as numerous bankers, lawyers, physicians, journalists, ministers, teachers and businessmen. (17) | ||

In later years, children who thought their "parents" were their biological parents often found themselves with nothing after their "parents" had died. These and others often had no idea where they were born or their names. Children in the 1800s in New York could be left at a church with no questions being asked. In other instances, a child might have only their first name pinned to their blanket. | In later years, children who thought their "parents" were their biological parents often found themselves with nothing after their "parents" had died. These and others often had no idea where they were born or their names. Children in the 1800s in New York could be left at a church with no questions being asked. In other instances, a child might have only their first name pinned to their blanket. | ||

| Line 106: | Line 100: | ||

Source: | Source: | ||

1. Kidder, Clark and Krantz, Colleen Bradford. "West By Orphan Train," Iowa Public Television presentation, December 1, 2014 | 1. "Orphan Train Riders to Iowa," IaGenWeb Project, Online: http://iagenweb.org/dubuque/orphans/05Sept1886.htm | ||

2. Kidder, Clark and Krantz, Colleen Bradford. "West By Orphan Train," Iowa Public Television presentation, December 1, 2014 | |||

3. "The Orphan Trains," The Children's Aid Society," Online: http://www.childrensaidsociety.org/about/history/orphan-trains | |||

4. "The Orphan Trains," An American Experience, Online: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/orphan/ | |||

5. Children's Aid Society. | |||

6. Ibid. | |||

7. An American Experience | |||

8. Warren, Andrea. "The Orphan Train," Washingtonpost.com Online: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/horizon/nov98/orphan.htm | |||

9. Children's Aid Society | |||

10. Moore, Alison. '''Riders on the Orphan Train'''. The Official Outreach Program of the National Orphan Train Complex. Online: http://www.ridersontheorphantrain.org/ | |||

11. Kidder et al. | |||

12. Ibid. | |||

13. "Orphan Train Riders to Iowa," Cyndi's List. Online: http://www.cyndislist.com/railroads/orphan-trains/ | |||

14. An American Experience | |||

15. Kidder, et al. | |||

16. Ibid. | |||

17. Children's Aid Society | |||

[[Category: Events]] | |||

[[Category: Humanitarian]] | |||

Revision as of 18:09, 20 January 2017

ORPHAN TRAINS.

Dubuque Sunday Herald

Dubuque, Iowa

05 September 1886

More Little Ones Coming

Agent Curren, of the New York Foundling and Orphan Asylum, to Arrive Here

with Fifty Children for People in this Vicinity.

The Herald is in receipt of a letter form Mr. Robert Curren, agent of the New York Foundling

and Orphan Asylum, stating that he will pass through this city on next Thursday, Sept. 9th,

with fifty more little children to be given to families at Epworth, Farley, Dyersville, New

Vienna and Luxemburg and a few will also be given to families in Fort Dodge. He adds that

fifty more will be brought to Iowa the 1st of October and will find homes with families

between Dubuque and Charles City on the Milwaukee and St. Paul road. (1)

Between 1858 and 1929 an estimated twenty-five homeless children from the streets of New York or the Children's Village (then known as the New York Juvenile Asylum), what is now the New York Foundling Hospital, and the former Orphan Asylum Society of the City of New York, which is now the Graham-Windham Home for Children found a new home in Dubuque. (2) They came by way of the "Orphan Train," a pioneering initiative which led to child welfare reforms, including child labor laws, adoption and the establishment of foster care services, public education, the provision of health care and nutrition and vocational training. (3)

In the 1850s, an estimated 30,000 children known as "street Arabs" were homeless in New York City. (4) Ranging in age from about six to eighteen, they lived in New York City's streets and slums with little or no hope of a successful future. Charles Loring Brace, the founder of The Children's Aid Society, believed that there was a way to change the futures of these children. By removing youngsters from the poverty and crime of the city streets and placing them in morally upright farm families, he thought they would have a chance of escaping a lifetime of suffering. (5)

Rev. Loring Brace proposed that homeless children could be sent by train to live and work on farms. They would be placed in homes for free, but they would serve as an extra pair of hands to help with chores. They would not be indentured. Older children were to be paid for their labors. (6) In 1853, Rev. Brace founded the Children's Aid Society to arrange the trips, raise the money, and obtain the legal permissions needed for relocation. (7)

Many agencies nationwide placed children on trains to go to foster homes. The orphans were scrubbed, dressed in new clothes and put aboard a westbound train at Grand Central Station. The children were not told where they were going or why. They had no idea that they were on an orphan train or that they had become participants in the largest children’s migration in history. (8)

Orphan trains stopped at more than forty-five states across the country as well as Canada and Mexico. During the early years, Indiana received the largest number of children. (9) From 1854 until 1929 an estimated more than 250,000 children were placed. (10) Between 1858 and 1910, a total of 6,675 children found new homes in Iowa. (11) Generally smaller towns were chosen for the children, but cities like Cedar Rapids and Dubuque are believed to each have become the homes of as many as twenty-five. (12)

A compiled list of people coming to Dubuque was developed by Madonna Harm over many years. (13) The following lists the orphan's actual name (or * adopted name), date of arrival, and person who took the child.

George J. Augmeier June 13, 1872 James Rea

Frances Bauer(*) John Bauer

Arnold Beckett Chapman

Henry Begley John Plaburne

Mary Broklin Adam Behringer

Rita A. Burnham Schumacher

Rita A. Byrne(*) Schumacher

Alice Crannan Rev. D. J. Slattery

Stella Knights Richard Powers

Moses Joseph Moritz Oscar Enders

Sara Moritz Oscar Enders

George Radford Martin Behyl

Amy Reichert (*) George Reichel

Frank Reigler (*) Reigler

Elizabeth Roche Wichman

Alma Rousseau Anna M. Bartholomew

Laura Seymour Monastery in Dubuque

Thomas Taylor Unknown

Clara Von Nostrand George Banworth, Sr.

George Frank Wichman (*) Wichman

Alice Wilson Anthony Digman

Alice Wilson John Klosterman

Catherine Wilson Elizabeth Ronan

James Paul Wilson Unknown

Placement into new families was casual at best. Handbills announced the arrival of the needy children. As the trains pulled into towns, the youngsters were cleaned up and paraded before crowds of "prospective parents." (14) In later years, "parents" wrote to the New York agencies requesting a certain sex, age, hair and eye color. (15) Some of the children struggled in their new surroundings. Children could live with a family for several months and then be sent back to the orphanage. (16) Others went on to lead normal lives. Although records were not always well kept, some of the children placed in the West went on to great successes. There were two governors, one congressman, one sheriff, two district attorneys, three county commissioners as well as numerous bankers, lawyers, physicians, journalists, ministers, teachers and businessmen. (17)

In later years, children who thought their "parents" were their biological parents often found themselves with nothing after their "parents" had died. These and others often had no idea where they were born or their names. Children in the 1800s in New York could be left at a church with no questions being asked. In other instances, a child might have only their first name pinned to their blanket.

Few of the actual orphans who were involved in the train remained alive in 2014. Their descendants, however, could number in the millions. For them the internet has proven a useful tool to find their heritage. Among other sites useful have been The National Orphan Train Complex: http://orphantraindepot.org/ and the Louisiana Orphan Train Museum: http://www.laorphantrain.com/

See: Riders on the Orphan Train

http://youtu.be/kexzcq8cXto

Orphan Train: Largest Child Migration

http://youtube.com/watch?v=G2nqLt5YGls

Orphan Trains

http://youtube.com/watch?v=cWTTcNBfaRw

---

Source:

1. "Orphan Train Riders to Iowa," IaGenWeb Project, Online: http://iagenweb.org/dubuque/orphans/05Sept1886.htm

2. Kidder, Clark and Krantz, Colleen Bradford. "West By Orphan Train," Iowa Public Television presentation, December 1, 2014

3. "The Orphan Trains," The Children's Aid Society," Online: http://www.childrensaidsociety.org/about/history/orphan-trains

4. "The Orphan Trains," An American Experience, Online: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/orphan/

5. Children's Aid Society.

6. Ibid.

7. An American Experience

8. Warren, Andrea. "The Orphan Train," Washingtonpost.com Online: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/horizon/nov98/orphan.htm

9. Children's Aid Society

10. Moore, Alison. Riders on the Orphan Train. The Official Outreach Program of the National Orphan Train Complex. Online: http://www.ridersontheorphantrain.org/

11. Kidder et al.

12. Ibid.

13. "Orphan Train Riders to Iowa," Cyndi's List. Online: http://www.cyndislist.com/railroads/orphan-trains/

14. An American Experience

15. Kidder, et al.

16. Ibid.

17. Children's Aid Society